There’s much to be learned from studying movements that thought they were the wave of the future, and weren’t. To begin with, there’s a distinctive tone of strident triumphalism that most movements doomed to fail seem to adopt, some at the very beginning of their trajectories, others once they pass their peak and start down the long slope into irrelevance. Learning to catch that note when it appears in the political and cultural movements of the present, by listening carefully to past examples, is one way to get some sense of the shape of the future well before it happens.

Yet there’s a broader value to failed movements for change, whether they happen to be religious, political, economic, cultural, or something else entirely. It’s a rare movement of this kind that doesn’t have something useful to teach. It’s even rarer for such movements to fail to have important things to say about the unmet needs and unspoken passions of their time. In the case of the movement we’ll be discussing here and for several essays to come, Situationism, both these are even more true than usual, for reasons we’ll explore shortly.

The Situationist International was one of dozens of little fringe movements on the outskirts of European Marxism in the middle years of the twentieth century. Its total active membership could have found seats quite easily in a modestly sized Paris bistro, and the fraction of its membership who contributed anything memorable to the movement could show up for an evening of conversation in the living room of my apartment without any undue sense of crowding. It produced a few journals, a flurry of communiqués, and a handful of books, and made a modest contribution to the atmosphere of unrest that inspired the French student riots of 1968, after which it fizzled out of existence and was replaced by other, equally marginal groups.

I freely grant that none of this may inspire any particular confidence in the value of Situationist ideas. As it happens, though, some of those ideas are worth close study. To understand why this is, we’re going to have to situate Situationism in its proper context—and that, in turn, is going to require a close look at the social ecology of Marxism.

To do this, it’s helpful to start with one of the basic principles of systems theory: The purpose of a system is what it does. (The helpful acronym POSIWID has been coined as shorthand for this.) As the delightfully named systems theoretician Stafford Beer liked to say, “There is no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.” Marxism is a fine case in point. Talk to any doctrinaire Marxist and you’ll be told that the purpose of Marxism is to pave the way for the inevitable overthrow of capitalism by the revolutionary proletariat, and thus to help bring about a utopian future in which private property will be abolished forever and each person will contribute according to his abilities and receive according to his needs.

This, however, Marxism has never done, nor is there any particular reason to think that this is something that Marxism will ever do. The rise of the revolutionary proletariat, the supposedly inevitable overthrow of capitalism, and the rest of Marx’s prophetic system still hover just as far in the indefinite distance as ever, as tantalizing and inaccessible as the Second Coming of Christ, on which the whole scheme was so obviously modeled. If the purpose of a system is what it does, rather, Marxism has two distinct purposes, depending on the nature of the society in which it operates. The purposes are different enough, and the social and organizational patterns that unfold from them are also sufficiently different, that it makes sense to speak of two different kinds of Marxism, which we will call alpha-Marxism and beta-Marxism.

Alpha-Marxism emerges in countries with little or no industrial sector and a large and politically powerful agrarian aristocracy—for example, Russia in 1917, and China and much of the global South after 1945. Its purpose in these contexts is to dispossess and destroy the landowners and the governmental system they control, replace them with a bureaucratic managerial aristocracy, and industrialize the economy. It does all this with tolerable efficiency, though extensive and brutal civil rights violations are also normally involved, and in the process it jumps over one step of the more usual three-stage process seen (for example) in western Europe and eastern North America: the replacement of landed aristocracies by capitalist “robber baron” aristocracies, which took place here in the late 19th century, and then the replacement of the robber barons by managerial aristocracies, which took place in the mid-20th century.

Beta-Marxism, by contrast, emerges in countries that no longer have a powerful agrarian aristocracy and have already made the transition to an industrial economy. Unlike alpha-Marxism, beta-Marxism never takes power or grows to anything much more than a fringe movement, but it still has an important purpose in the workings of modern society. In every generation, a certain number of youths from the managerial class are dissatisfied with the status quo. Beta-Marxist parties are among the marginal groups that absorb their energies and direct those into channels that are harmless to the managerial state.

Such groups also help stabilize society in an intriguing and indirect way. Where alpha-Marxists generally focus on effective means of seizing power and leave theory to the academics, beta-Marxists usually combine highly cogent theoretical critiques of the existing order of society with feeble and ineffective means of attempting to change that state of affairs. The critiques, shorn of rhe dead weight of ineffective technique, are then brought into managerial circles, once the formerly disaffected youths get bored of Marxism and settle down into the jobs their class status guarantees them. In this way the managerial state can sometimes get ahead of genuine movements for social change, handing out reforms to placate this or that dissatisfied group and stave off trouble. All in all, it has a certain elegance.

I should probably mention in advance—since some of my readers will doubtless bring this up—that a case could be made that the labels alpha-Marxism and beta-Marxism ought to be assigned the other way around, because beta-Marxism is actually the original form. It wasn’t until Marxist ideas seeped out of western Europe into Tsarist Russia and the global South that alpha-Marxism had a chance to emerge. I’ve chosen to use the labels as given, however, because of the meanings of “alpha” and “beta” in modern slang. Alpha-Marxists, after all, do tend to behave like alpha males, complete with the swaggering arrogance, the aggressive quest for privilege, and the tendency to outbursts of brutal violence in response to any show of opposition.

For their part, those beta-Marxists who stay in the movement for the long run and form the backbone of beta-Marxist organizations tend to be drawn from among the also-rans of industrial society, those who by temperament or talent aren’t well suited for a salaried position among the bourgeois enablers of the managerial aristocracy, and who exchange the prospects normal to their class for downward mobility and a place on the fringes. Those that are good enough at the game end up being supported by the broader society, because they provide the service described above—catching disaffected youth who might otherwise become a genuine danger to society, and redirecting their energies into some colorful but harmless form of eccentricity, while exposing them to various critiques of the existing order of society that may be useful to them later in life.

Of course Marxism is far from the only ideology that fills some version of this same role. Every complex society has an assortment of dissident belief systems, and these form a penumbra of alternative options out on the fringes of the culture. Some complex societies object to this state of affairs and try to get rid of the dissident fringe through one means or another, with recurring bouts of mass murder a common option. Modern industrial society, having learned a few things from history, takes a different tack and tacitly permits the fringe ideologies to exist and even thrive while overtly discouraging membership in them.

There are good reasons for this tolerance. Partly, campaigns of extermination are costly in terms of resources, and they also give a glamor to dissident groups that their own beliefs and actions do not always deserve. What today’s beta-Marxists resentfully call “repressive tolerance”—that is, allowing fringe ideologies to flourish unmolested while using propaganda and other means of controlling popular opinion to limit public interest in them—is much more economical and even more effective as a means of repression.

Yet there’s another factor. To borrow and rework a turn of phrase from Marx, the fringe constitutes a sort of reserve army of unemployed ideas, any of which can be drawn upon at need to fill gaps in the existing ideological structure of society. That possibility is anything but abstract. It quite often happens, in fact, that belief systems and their associated groups that once were part of the established order of society get eased out onto the fringes, while other belief systems that once survived on the fringes find their way into the establishment.

Consider the trajectory of conservative Protestant Christianity over the last century. It’s hard to think of any set of ideas more thoroughly hardwired into the social structure of the American mainstream in 1910; it’s hard to think of a set of ideas that had been more completely excluded from that mainstream by 2010. In the same way, but with the opposite dynamic, consider the trajectory of the gay and lesbian subcultures; it’s hard to think of anything more harshly excluded from the mainstream in 1910, while by 2010 both had been integrated into the mainstream. That conservative Protestant Christianity was affiliated with the Democratic Party in 1910, just as the gay and lesbian subcultures were in 2010, just adds a nice fillip of irony to the landscape of social change.

Now, in an interesting contrast, conservative Protestant Christianity seems to be moving back into acceptability just as the gay and lesbian subcultures seem to be moving out of it. That may not be a mere accident of history. In the late 20th century, many people in the United States were worried about overpopulation, and so it isn’t exactly surprising that belief systems that encourage propagation moved toward the fringes while those that discourage it became much more acceptable. Now that the population boom is ending and depopulation is on the horizon, popular culture is shifting in the other direction.

Meanwhile there are plenty of other groups and ideas that have been shut out of the mainstream for a very long time and show no signs of finding their way further in any time this millennium. Beta-Marxism is one of these, but far from the only one. There are plenty of alternative groups in that category, ranging from fringe religions to proponents of exotic economic theories to the fans of invented languages such as Esperanto. While they vary in some ways, notably in the level of hostility they direct toward the established order of things, the common features greatly outnumber the differences.

As all this may suggest, the penumbra of fringe ideas and their proponents is a social category I know fairly well. That’s not surprising, since I belong to it. I might have ended up a beta-Marxist, in fact, if I’d made a few different choices in my late teens. Back then I was an amused but interested spectator of the fringe Marxist parties in Seattle, whose antics I followed in some detail by way of their monthly newspapers, which could be purchased at the Left Bank Bookstore in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. In those days the two big fish in that very little pond were the Revolutionary Communist Party and the Freedom Socialist Party, though there were also even smaller parties that appeared and disappeared like mushrooms after a rainfall.

All this was grist for my mill back then. I read the doings of the local radicals fairly regularly, attended the occasional rally and protest march, and drew my own conclusions from the mismatch between their angry and grandiose rhetoric and their complete inability to make any kind of difference outside their own membership, and tolerably often, not even there. Mind you, I also paid attention to the equally unrewarded labors of wholly non-Marxist political groups such as Technocracy, which still had a presence in Seattle in those days, to a variety of other alternative scenes, and also to the occult scene, which ended up becoming the branch of fringe culture that ended up attracting my enduring attention.

The conclusions I drew were not exactly flattering to the pretensions of beta-Marxists. Life on the fringes has its consolations, notably a great deal of personal freedom, but it also has costs, and a lack of political influence is one of them. Thus beta-Marxists are no more likely than beta males to overthrow the system. One of the things that differentiates me from beta-Marxists is that I’m fully aware of that fact, and of my function in the wider structure of society, while their ideology forbids them from ever noticing this. Still, their limitation need not hinder those of us who hope to make more productive use of their insights.

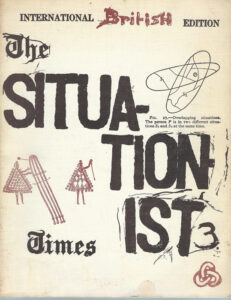

Situationism was one flavor of beta-Marxism, and partakes of all the standard characteristics of that broader phenomenon. It emerged out of several rather less memorable micromovements that rose and fell just after the Second World War, among them Lettrism and Imaginism; like these, it had its birth from the fusion of radical politics and the arts that began with Dadaism during the First World War and arguably reached its peak with the Surrealists between the wars. That’s where the term “Situationist” came from: the Situationists began as an artistic movement that imagined the creation of entire situations for esthetic purposes, and then morphed into a political movement as the political implications of these creative acts became clear.

From its mixed parentage, Situationism picked up an equally mixed assortment of habits. One of them was the strident insistence that while there were Situationists, there was no such thing as Situationism, no ideology or set of ideas that united the movement. Of course this is nonsense—the ideas in question can be found set out in detail in books by leading Situationists—but it was a common pose of avant-garde artistic movements of the time, and it was also a helpful countermove to the obsessive fixation that more orthodox Marxists had on embracing the correct ideology (another of the habits Marxism borrowed from Christianity).

Another example was the systematic refusal of Situationists to embrace the organizational forms standard for radical movements of their time: the political party, the organizing committee, the trained units of brawlers ready to mix it up with rival groups, and the rest of it. Partly this was a recognition of the way that those forms so easily got coopted by the existing order of society if they got large enough to be noticeable, but partly it reflected the usual practice of avant-garde artistic movements, which gave each artist as much leeway as possible while still preserving a façade of shared identity. Mind you, none of this kept the Situationist International, the mostly disorganized organization that waved the banner of Situationism over a variety of European cities for a decade or so, from replicating most of the more embarrassing habits of beta-Marxist groups worldwide.

To see those in action, it’s helpful to read the articles and essays that appeared in the journal Internationale Situationniste and other Situationist periodicals, either in Ken Knabb’s capably edited collection Situationist International Anthology or, better still, in online archives of the movement which preserve the texts in their original settings (in French and English translation). Here you’ll find the sneering denunciations of alternative views, the acts of excommunication consigning an assortment of heretics to the abyss, the strutting self-importance of those who insist on seeing themselves as history’s vanguard even though nobody else notices their existence, and the rest of it. It’s all very reminiscent of a teacup poodle barking frantically at a Great Dane, trying to make up through sheer shrillness what it lacks in size and strength.

At the same time, other features of the movement come through here and there, like glimpses of an unfamiliar landscape seen through mist. Now and again, the Situationists took into account the realities of the social setting in which they operated, even when those contradicted (as they generally did) the precepts of Marxist dogma. Now and again they took on the flaws in Marxism itself, and reached toward ways of making change that didn’t just rehash the failed prophecies of proletarian revolution and the rest of it.

It’s important to keep all this in mind, so that Situationism can be seen as what it was and not what it wanted and pretended to be. What it was not, of course, was a means of overthrowing capitalist society, or even taking the most modest step in that direction. What it was, at its best, was a cogent critique of certain crucial features of modern industrial society (capitalist or socialist) that have not been as clearly recognized anywhere else, and a first tentative sketch of a set of strategies that leverages the strengths of fringe culture against the weaknesses of the established order to expand the possibilities for human freedom. We’ll discuss all this in upcoming posts.

What right wing ideologies today behave like beta-Marxism?

What a brilliant sobriquet: “beta-Marxist”. Not to mention your analysis around it hits on so much truth. Works on multiple levels and deserves wider adoption.

When I was at Cornell in the early 1980’s the most popular class from the most popular professor in the economics department was on Communism. At the time,this seemed surprising to me, that such a class would exist in an obvious training ground of the PMC.

But your explanation of the purpose of Beta marxism explains it perfectly. I never took the class, but it was talked abut frequently around campus. I still remember the most common comment from those who were taking the class, ” If you are not a communist, you are not really thinking”.

I look forward to the discussion of useful strategies that the situationists came up with. The conventional narratives seem to be cracking, and they desperately need a bit more shaking up.

Though they seem to have cracked more in some places than in others. My area of coastal BC seems to be one where the narrative is pretty solidly in place among the vast majority of the people I run into. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some of them are mouthing platitudes they don’t believe, but it’s hard to even be silent here, let alone put forth different ideas among people I meet in the real world. I listen a lot more than I speak with almost everyone I know.

POSIWD is so obvious but rarely recognized. It is a useful tool for cutting through baloney. For example, if you looked at the system of slavery in the United States, all the grandstanding about uplifting and civilizing the negro is revealed to be a farce, the real purpose is the obvious one (producing cheap goods at a high profit).

Similarly, applied to industrial civilization, all the rhetoric about human progress evaporates and we are left with the real purpose: recklessly extracting natural resources as fast as possible to produce wealth for a small group of elites.

I like the fringe on my cut off jeans just fine… not bored at all… not bored.

…Lettrism, while of not much interest to many, does have its joys for those of us like me interested in these small artistic / political groups.

The excommunication reminds me of something from Robert Anton Wilson, where he made people popes, and then promptly excommunicated them so they could be their own popes… or something along those lines. I have a business card from him with something like that on it that came with the Maybe Logic DVD -and it had the motto “like what you like and don’t take [shale] from anybody.” So, in a way I can see this as a potentially useful habit of fringe groups excommunicating each other.

Guy Debord as the main ring leader, though he wouldn’t want to call himself a ring leader, was a major drunk, and I can see some of the interpersonal friction within that scene just coming from being an intoxicated intellectual jerk (you had a name for this in French culture, which they took for granted but us Americans don’t seem to get off the bat).

Asger Jorn was one of the excommuniques who I rather like. Especially his triolectic football. More broadly his notion of moving from dialectics to triolectics I find would be very useful!

Of the tools created by Situationism, detournement as culture jamming really got utilized to a high degree by media collective Negativland (who coined the term culture jamming, based on their work documenting / making art out of ham radio jammers in Berkely area) and others who followed their path of editing the fragments emerging from the media spectacle into new creations. Meanwhile psychogeography really got a hold in England, though not so much here. Other early culture jammers were influenced by the SI as well… people like the Billboard Liberation Front.

As another commenter mentioned, the punk subculture owes a large debt to the writings of SI, and key elements of Situationism can be traced in the Sex Pistols, Crass, The Clash, and others…

Speaking of fringe culture and the reverse osmosis of assimilation / excommunication, the next entry in my National Characters / American Iconoclasts series is up here. It’s about the Birth of Freeform Radio and the Crazy Wisdom of Wes “Scoop” Nisker who embraced paradox and ended his shows with “If you don’t like the news… go make some of your own.” Useful advice now as it was in his heyday.

https://www.sothismedias.com/home/the-birth-of-free-form-radio-and-the-crazy-wisdom-of-wes-scoop-nisker

I was a college-campus Marxist when I was in school, and the reason it turned out to be a five-gallon bucket of fail was that “politically correct” ideology rendered what you call beta-Marxism even more neurotic and dysfunctional than when it started out of the gate. I think I ended up being alienated from it because, while it initially fostered some good, solid questioning and thinking, it soon ended up entrenching my neurotic and dysfunctional tendencies that were preventing me from truly growing up. That is why I think Spirit pretty much arranged for me to become socially alienated from it immediately after I was done with school. Having to stand by myself in a steaming garbage-dump of a society without the armor of that ideology left probably the most enduring emotional impression of my formative years.

Anonymous, Dark Enlightment crowd, i think.

Do you think the fringe relates to what Yeats calls the antithetical tincture, and the lamestream as the primary tincture?

I too have looked at “beta-Marxist” over the decades. I still read well-written Marxist books that examine modern capitalism and imperialism. What I’ve seen is that as a group ordinary beta-Marxists tend to be misfits who because of lack of social skills, technical skills, or just inclination, cannot be part of mainstream bourgeoisie society. Their talk is grandiose, they talk of the impending revolution (at some unspecified time) and they tend to have a grossly inflated opinion of themselves, seeing themselves as a “revolutionary vanguard.” Very few of them have actually read even the first volume of Marx’s “Capital.” Some of them could be seen during the so-called Occupy movement of fourteen years ago. One more thing I want to mention in passing is that they seldom practice what they preach — if one of them were to win a lottery and come into $20 million he or she would promptly become bourgeoisie and forget his or her erstwhile radical leanings, just as a suddenly enriched pauper throws away the rags he has hitherto been attired in. Why do I say this? Because their selfishness and self-centeredness is clear to see beneath the radical rhetoric.

“What right wing ideologies today behave like beta-Marxism?” – I suspect that many visible right wing groups do not have much or a coherent ideology. The left tends to build theoretical castles in the air, and then when the ideas are picked up by a genuinely disadvantaged group who can use the ideas to validate their actions they become like alpha Marxists. Both National Socialism and Neo-Liberalism achieved this from the right, enabling a relatively small core group to change the direction of society. In the case of Neo-liberalism without a mass movement of support, thus creating one of the few genuinely revolutionary changes without mass violence (albeit plenty of covert non-physical violence). Both had a more or less coherent ideology.

The right wing groups we see waving flags on the streets of the UK today are more like movements without an ideology. Reacting to knee-jerk ideas rather than attempting action based on reflection like the beta-Marxists. Behind them the leaders are very much part of the establishment, stirring up a mass to promote their ambitions. To that extent they will seem to achieve more success than the betas could dream of, but it it will not be significant social change – the old order will persist.

The White Nationalist scene and related movements behave exactly like beta-Marxism, down to the impossible revolutionary schemes, the small groups gathered around one or two articulate leaders, and the catfights with related groups. Some of their ideas are being pressed into service now, to shore up the system at various weak points.

POSIWID has been strongly criticised as reductive and, ironically, Marxist. It all depends where you stand of course, since the judgement about what a system “really” does is inevitably subjective. My favourite example is the US military system, which provides direct employment to a million people, as well as medical care, indirect employment to millions more, and injects billions of dollars a year into the economies of other countries through overseas bases, and expenditures of soldiers in bars, discos and, um, other places. So in fact it’s purpose is a charitable one.

I think it’s also important not to reify ideas. Marxism is, after all, a system of thought and analysis which has no agency in itself. Individuals calling themselves Marxists, and seeking to justify their actions under that banner have formed movements and organisations, although as with most labels of that sort (“democracy” is probably worse) all sorts of different results are possible. “Marxism” as implemented by Trotsky would have been different from that implemented by Stalin, although the formal CPSU party structure might not have changed at all.

Finally, It’s important not to forget the French and Italian Communist parties, (“Betas”) in your terms, which were major political forces after 1945, regularly getting 20% of the vote in elections, and running important towns and cities (this hasn’t entirely finished.) Much of the postwar instability of Italy is explained by the need to put laborious coalitions governments together which excluded the Communists.

I’d be interested to see how your essays develop. I’ve tackled another aspect of the same subject– thepost-1968 life of many of the ideas of the era, in which of course the situations played a major role. I hope you’re going to let us have your thoughts on Guy Debord.

JMG, from the way you always express yourself, I’ve long known that you are a disappointed Marxist. Good to see you admit it. There’s a kind of determined cynicism in your attitude to The Left which is a dead giveaway. Quite understandable, of course.

Thank you for this post, which served as a helpful jolt to my own consciousness.

Did you ever encounter a set of ideas, internalize them, and then forget where you had learned them, all the while they’d been running in the background of your consciousness for years? I have that sort of relationship with systems theory. I studied it in as much depth as I could (admittedly, not very much) in college, and have had it running like hidden software in the background of my mind ever since. “The purpose of a system is what it does” is one of these immensely useful ideas which clarify a very great deal that seems otherwise mysterious.

I was never a beta-Marxist, because Marxism never appealed to me. Instead I was a beta-anarchist– or just an anarchist, since there have been few if any alpha anarchists outside of Spain in 1936, and perhaps Ukraine in 1918. Six of one, half dozen of another; the structure of the thing was the same.

It always seemed to me, though, that we had a perfectly good thing going, enjoying alternative lifestyles and genteel poverty in our networks of collective houses and the like. I enjoyed revolutionary talk as much as anyone– it’s nearly as good as an amphetamine– but would really have preferred to keep doing our own thing on the margins of capitalist society, and leave everyone else out of it. Of course, that’s exactly what everyone else wanted, too– but almost no one was willing to admit it. Oh well.

That was all many years ago. Recently I said to some friends that I’ve come to look on that time as one part initiation, one part inoculation. An initiation, because I learned skills which serve me to this day both in the realms of personal independence and interpersonal relations. An inoculation, because I’m largely immune to the pressures of radical politics of any stripe at this point. And according to your analysis, that was precisely the point!

Anonymous #1: the “White Nationalist” and “National Socialist” wings of the Dissident Right are absolutely beta-Marxist in spirit. Wearing swastika armbands and screaming racist slogans in public is a singularly poor way to gain political power. But it’s great for gathering a small, dedicated coterie of people who pat each other’s backs and feel superior to the Cuckservatives who aren’t hardcore enough to accept the Real Truth.

The Internet has also become a fertile breeding ground for every loony political cause. And of course you get the endless denunciations, excommunications, and internecine squabbling JMG mentions in his essay. While many people claim the Internet radicalized America, one might just as easily argue that the Internet is a giant pressure valve that lets people engage in performative radicalism without actually getting their hands dirty or endangering the social order.

I’m currently reading Adorno & Horkheimer’s “Dialectic of Enlightenment.” The Frankfurt School was more influential than most beta-Marxists, but it has the same dreary habit of trying to shove everything in a Marxist lens. A & H interrupt a thought-provoking essay on the roles of myth and reason in early history for a discussion of how the engagement between Odysseus and the Sirens is a harbinger of the bourgeois takeover of the systems of power and their willful deafening of the Proletariat. I gotta admit I got a hearty chuckle out of that passage, though I doubt very much that was what the authors were aiming for.

Alpha- and beta-marxism are excellent coinages! I hope your essay helps lay to rest those fears of somebody implementing “Communism!” or “Marxism!” in the near future in countries like Canada, the USA or Brazil.

I would add an additional category: ex-marxism (call it chi-marxism if you want). There are parties that originally espoused Marxist theory, but as their membership ballooned among the working-class population, they abandoned Marxist tenets for more pragmatic goals like universal health care, affordable housing and some degree of worker control of enterprises. The example I know best is the Social-democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which turned its back on Marxist revolution, in practice, in 1918/1919, and then even in theory at its Godesberg congress in 1959. I suppose the Scandinavian, Dutch and French social-democratic parties underwent similar transformations. It might be (though I am not sure) that even the French and Italian communist parties went a similar path.

Hello JMG and kommentariat. I can say Situationist poster is cool…Thanks for the links to Situ texts in original French and English translation. I used to read Situ stuff when I was a (late) teenager, although I thought sometimes they were a bit nuts, or they simulated being nuts. Am I explaining it well?

————————————-

(Slightly off topic) This is a message for Achille. I’ve read a lot of the web “virtud y revolución”, and well, I’ve realized soon they’re “traditionalist anarchist”, I suppose for “serious” Anarchists (if this cathegory exists nowadays, I doubt it). From my point of view, they’re partly right in their critics to established Left and Right. However, they are too radical for my taste…

NephiteNeophyte @ #5, speaking of POSIWID, the welfare agencies come immediately to mind, their purpose being a jobs program for the less competent among college graduates.

Existennial Comics is produced by some sort of establishment feminist anarchist, and it occassionally takes potshots at the ideas of Karl Marx.

I love “Communist Brainstorming” where radical philosophers think of ways to overthrow the bourgeise. The solution they come up with is unorthodox yet surprisingly effective:

https://existentialcomics.com/comic/389

@Steve T: ” enjoying alternative lifestyles and genteel poverty in our networks of collective houses and the like.”

Sounds like a good time to me…

I always enjoyed reading anarchist philosophy, but was always bored by Marxism. The two were bedfellows often enough, but anarchism just as often had other inclinations as well.

I’ll think of myself as a theta-Anarchist to tie it in with the 8th letter of the Greek alphabet.

Anon, nearly all the neo-Nazi and neofascist groups, the Dark Enlightenment and Neoreaction scenes, and some of the right-wing Transhumanist groups, just for starters.

Tomfoolery, thank you, but it seems very obvious to me!

Clay, I think it was Churchill who said, “Anyone who is not a Communist at twenty has no heart; anyone who is still a Communist at forty has no brain.”

Pygmycory, that doesn’t surprise me at all, I’m sorry to say. I hope you find some of the Situationist insights and tactics useful.

Nephite, exactly. Apply POSIWID to everything, and especially to the ideas you believe in most strongly; the results are always useful.

Justin, oh, granted. Lettrism actually helped me develop my concept of the life cycle of artistic movements, though I think Isou badly underestimated the potential for creativity in the performance phase, when the creative space is filled — there’s more to be done than chiseling!

Mister N, it’s a common experience — glad you came through it more or less in one piece.

Justin, it depends on whether the collective phase is primary or antithetical. In collective primary phases — we’re in one of those now — the fringe is antithetical; in collective antithetical phases, the fringe is primary.

AA, you’re certainly right about how shallow the rhetoric is. A good many of the beta-Marxists I’ve known were trust fund tragedies — they denounced capitalism while living off monthly checks from trust funds invested in the stock market. It’s mostly just a pose.

RogerCO, we have a rightist movement of that sort here in the US, too — purely reactive, focused entirely on returning to something less toxic than the latest antics of wokery. It’s fairly powerful these days, not least because it helped put Trump in the White House. Look around, though, and you may find that there are also ideologically intense groups on the right.

Aurelien, the US military certainly isn’t in the business of fighting wars, a job it does very ineptly at best. I’d characterize it as a gravy train for corporate interests, with giveaways to other pressure groups; that’s what it does, and so that’s its purpose in POSIWID terms. I grant that reification can be problematic, but so can idealization — claiming that there’s this thing called “real Marxism” out there somewhere, doubtless rubbing shoulders with Plato’s ideas, is among other things camouflage for the way Marxist groups actually behave. As for France and Italy, that’s a valid point, but I’d note that after the war, French and Italian industries had been devastated and both nations were in a very real sense industrializing rather than industrial nations. As that process completed itself, the Communist parties in both nations transitioned from alpha-Marxism to beta-Marxism.

Ben, that’s not quite accurate, as I was never a Marxist. In my radical phase I was a democratic syndicalist with some influence from guild socialism via Chesterton and Belloc. The determined cynicism is there, to be sure, but it doesn’t take membership in a Marxist party to become very deeply soured on Marxism; in my case it was partly a matter of watching the antics of the parties I cited, and partly spending a couple of years in my mid-twenties working as a nursing home aide and talking during quiet hours with a young man from Cambodia who had the same job. He and his sister survived the Khmer Rouge regime. The other forty-odd members of their extended family did not.

Steve, I’ve had that same experience many times. For example, it wasn’t until I reread the Illuminatus! trilogy a couple of years ago, after about a decade during which it sat neglected on the shelf, that I realized how strongly it influenced The Weird of Hali! But you’re right that life on the fringes is partly an initiation and partly an inoculation; it can also become an enduring lifestyle, for those who can figure out how to make a living at it, as I have.

Kenaz, so you’re tackling Adorno and Horkheimer! One of these days I need to waste a year or so writing a book-length deconstruction and détournement of that sadly influential work– “waste,” of course, because the resulting book will be read by about fifteen people in the subsequent history of the universe, if that. Unpacking what A&H have to say from the standpoint of occult philosophy will nonetheless be a treat, at least for me.

Aldarion, “chi-Marxism” is funny and useful, as I don’t happen to recall what “selling out and cashing in” works out to in Greek. Yes, it’s an important factor, not least because there are also parties such as our Democratic party which borrow Marxist rhetoric but remain hopelessly bourgeois, and in fact grand-bourgeois, in their attitudes. I’m not sure what to call them — phi-Marxists, with the phi standing for “faux”?

Chuaquin, the Situationists were a bit nuts. That’s one of the reasons they’re valuable. In a late industrial society, going at least a little nuts is the only sane alternative. 😉

I will also put in another plug for Mackenzie Wark’s excellent history of the Situationist movement, The Beach Beneath the Streets, published by Verso Books.

Another interesting title from the Leftist press Verso was Breaking Things at Work :the Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job by Gavin Mueller. If it had more Luddism and a lot less Marxism I would have liked it more.

I thought about making a list of beta-ideologies but I realized it boils down to one nearly infallible rule: if an ideology has a name and is almost entirely subscribed to by college students and graduates, it’s a beta-ideology.

For myself, I’m a disappointed anarchist. After about a decade I noticed that it was just a sink to preen about how much better your ideology is than either major party while abdicating any and all responsibility for politics in the real world, which I hardly need a sophisticated ideology to do!

That or throw bricks and get in fights to impress women. (I wish I were joking.)

For better or worse there has only ever been one alpha-anarchist of any note: Buenaventura Durruti. Everyone else is a beta or beta pretending to be an alpha. Or worse, like Hakim Bey.

Anonymous #1,

There’s a local group that gets together to read things like the Federalists and Anti-Fedralists, various correspondence of the Founding Fathers, etc. I suspect they are one of the right-wing ideological equivelents. They occasionally manage to get up a counter-protest to one of the inevitably geriatric and sparsely populated leftist protests.

(Those of us who are younger are absolutely scathing on the local rags’ comment sections about these: Oh, did the nursing homes have an old hippie park field trip? sort of snark.) However, local demographics, there are no observable young person’s movements. Both sides are the retirees.

Any young person stuff would be in video game chat channels, and as a Gen Z Mom, it is wild hearing “So in Judges 8 we see-@#$&! you @#$&!- that when Israel . . . ” when the kids are running themselves a Bible Study and a game raid at the same time.

Middle aged seem to be busy wrangling the older generation and the younger generation at the same time, and I suppose the closest to social philosophy we usually manage is “Well, we like Plato and a Platypus walk into a Bar, and Heiddeger and a Hippo walk through those Pearly Gates, for intro to Western Philosophy texts. The kids retain the broad strokes because it’s all jokes.”

I’d second Aurelien’s criticism of POSIWID. If applied too strictly, it seems like it would mean that the purpose of every defeated side in a war was to lose that war (though, of course, many losers end up looking that way in retrospect…). That said, I can definitely see its value as a lens for analysis. Those “beta Marxists”, and many others like them, may have been working in their inept and delusional way towards a very different purpose, but the function they end up performing in society is as you say. I’m also not sure that this function was something most in the elite have thought a lot about – it may have been enough for them to conclude that those people were mostly harmless – but the outcome is the same. And when a process consistently achieves the same outcome over and over again, it’s definitely worth noting regardless of what we make of stated intentions.

@Steve T #15 “I enjoyed revolutionary talk as much as anyone– it’s nearly as good as an amphetamine– but would really have preferred to keep doing our own thing on the margins of capitalist society, and leave everyone else out of it. Of course, that’s exactly what everyone else wanted, too– but almost no one was willing to admit it.”

Once again I find myself thinking that I’d be really into anarchism if it dropped those revolutionary pretensions, which strike me as at best annoyingly disingenuous and at worst self-destructive. If people in such groups could admit that a revolution was neither possible nor, in light of historical experience, desirable, and instead concentrated on improving their life on the margins… well, they would appeal a lot more to me and probably a lot less to some others. But they may also gain something from such honesty.

@ Justin– It was quite a good time, if you were willing to learn the secret passwords. Certainly the Clash (which remain my favorite band) were heard very often at our parties. I began to distance myself from the “movement” when I started practicing daily banishing rituals in 2013 and discovered that all of my old friends had taken on the appearance of bloated fish-monsters. A year later I learned the mental practice of “resolving binaries” from JMG, applied it to the Trayvon Martin affair, and was summarily purged.

(Well, that’s the rough outline, anyway.)

One of the funniest things about far extremist left is the fear/hate whem they say the ominous words: “reformist” and “socialdemocrat”. There’s a lot of comedy in it, although involuntary.

By the way, I suppose there’s the same BS in the Right, with far Right freaks scorning mild Conservatives as moderate…

JMG #22.:

John, it’s good to hear that about getting nuts; in fact, I am myself a bit nuts too…

JMG,

I never got around to reading Illuminatus, and should probably rectify that! Now, though, I’m thinking about what else I may read 20 years ago that’s still shaping my thoughts.

One thing I find fascinating is the way that certain fringe ideas have migrated from the “left” to the “right” in the past decade. When I think of the “fringe-as-initiation,” one of the things on my mind is the use of herbal medicine, which I picked up in my anarchist daze and have carried on ever since. Fifteen years ago, holistic healthcare (of every sort) was a left-wing affair, associated with hippie communes and Northern California. Now it’s a right-wing thing, associated with trad wives in South Appalachia. From my own perspective, I just want to treat common ailments with plants gathered from the woods behind the house. I don’t want to be part of any political movement, since there isn’t one I agree with. But the strange reversals of the past decade, and the way that so few many people have gone along with them without remark– often enough, apparently, without any memory of their former positions or awareness that they’ve changed– remains the weirdest thing I’ve ever lived through.

On Reddit, I noticed a clear distinction between the theory-light, doomer-heavy American beta-Marxist crapposters on the Late Stage Capitalist subreddit, and the well-read beta-Marxists that seem to be older and from Eastern Europe who post on other communist subreddits.

The former is the left wing of present-day progressivism, and as ideologically shallow as any other wokel; the latter seem to have members that were educated in Marxist-Leninism back before the collapse of the Soviet Empire (however, even they are wokeified, probably by aggressive commemt moderation).

Disclaimer: I haven’t spent enough time on those subs to know for sure if my characterization of the doctrinaire Leninists is accurate.

JMG, as a contemporary example of what you described in your last paragraph, cogent critique, tentative description of set of strategies, etc. I would like to draw your and commentariat’s attention to this charming group of anarchists in the UK:

https://winteroak.org.uk/2021/12/28/the-acorn-70/

What I like about this group is their focus on environmentalism; they are not your typical high urbanites sneering at “the establishment” over their lattes.

This essay gives quite a bit of food for thought. 🙂

What I’m grasping so far (although admittedly this may not be *very* far) is that the point of Marxism – as evaluated by what it accomplishes – is to act as the midwife (alpha-Marxists) and/or baby-sitter (beta-Marxists) for the process of Industrialising? or maybe for the process of bureaucratising? a society.

Although in some countries, the birth of industrialisation, but not of bureaucratisatiion, was first attended by capitalist robber baron midwives, before Marxism had properly developed.

In other words, by this reckoning, Marxism is very closely intertwined, possibly irreducibly, with the industrial/bureaucratic nature of THIS society.

Am I on track? or have I gone grieviously off the rails?

About Comunism and industrialization, i think you are right on target. That’s why even when comunism speaks of peasants and workers, it always wants to destroy the formers and their communities, and turn them into the later.

That’s also the reason that lead Stalin to quickly dismantle the NEP and proclaim that the country was going to Industrialize, at any cost, because it was either this or be crushed by the western powers.

Considering the methods he employed however, which included , aside from the well-known extermination of the “kulaks”, creating famines on purpose to starve the country side, while at the same time forcing the desperate country-people to the cities to be employed in factories, it might have been better for the Russian people to wait for the Germans to invade them. The body count may well have been much lower!

I’ll add a charachteristic to your description of alpha-comunists, however: They tended to be very succesful preachers and propagandists. Trotski was credited with the ability to walk into an isolated village, full of distrustful and scared people, and walk away followed by a crowd willing to fight into the then incipient Red army. The same ability still existed in the Spanish Civil war, where Communists started as a very small party and ended the war as the dominant and most popular faction, even failing at almost everything!

Guillem.

@Slithy Toves: When I was first introduced to Hakim Bey and TAZ around age 17 or 18 I loved it. The same when I read his Immediatism and other works around 22. Fast forward a number of years and I reviewed several of his more recent books, then found out about some of his other, uh, inclinations. Re-reading bits of him later I was able to pick up on those inclinations in his text that I’d missed the first time. My taste for it was done.

That said I was inspired by real world TAZ examples such as Dreamtime Village. I’m not sure how that experiment has played out in its later years. But it reminds me of the talk here on the ghost towns in the future desertified west. Good place for nomads to take up… though I doubt they’ll be pacifists… I’m reminded with the ghost towns of the YouTube channel Ghost Town Living. Of course that guy has lots of money to put into his Ghost Town. Still the model might work for some form of collective.

Justin, I doubt Mueller broke things at his own job!

Slithy, that’s probably the best touchstone, yeah. As for alpha-anarchists, no question, Durruti was the man; I think there have been a few other anarchists who had comparable roles, but anarchism’s a miserably difficult ideology for that sort of thing, as its sole purpose (by the POSIWID standard) is to fail and get people killed. As for Peter Lamborn Wilson aka Hakim Bey, well, yes. Ick.

Daniil, POSIWID can’t be applied to a single instance — for example, one war. If a given country repeatedly started wars and lost them, especially if it lost them in the same way every time, then you could apply it. (This offers an interesting insight into the history of Germany.) You’re right that the ruling elites doubtless haven’t given a single moment of thought to the fringe groups and their social function; one of the advantages of systems theory is that it makes it possible to see social processes as emergent functions that nobody planned, rather than getting stuck in a cascade of “who set out to make this happen?” fallacies.

Chuaquin, it is indeed the same thing on the far right. The blistering scorn with which Marxists denounce liberals is matched point for point by the blistering scorn with which neofascists denounce ordinary conservatives. As for being nuts, of course you are — anything else would be crazy!

Steve, that’s one of the most fascinating changes of my lifetime. I’ve changed very, very few of my beliefs since my late 20s, and yet in that time I’ve drifted all the way from the extreme left to the moderate right. Alternative medicine? Opposition to centralized government control by bureaucratic “experts”? A taste for retro tech? Support for small local businesses? A conviction that individuals ought to be left free to lead their own lives without having official busybodies hassling them? Those used to be positions of the extreme hippie left when I was a young man; they’re standard on the right at this point, while the left has embraced nearly all the opposing points of view.

Patrick, I haven’t been on that end of Reddit enough; most of where I lurk is in the occult and alternative-realities subs. I’ll have to visit r/latestagecapitalism one of these days.

Mary, thank you for this! An anarchist movement that rejects the latest high tech boondoggles and is skeptical of the pharmaceutical industry — gosh, I feel twenty again. 😉

Scotlyn, you’re not off the rails at all. Marxism is an ideology of bureaucratic power — that’s why so many Marxists nowadays focus all their ire on the capitalist class, the people who get their income from investments, and go out of their way to ignore the power of bureaucrats, who get their income from government salaries. Some Marxists want to become government bureacrats, others want to bring about a society run entirely by government bureaucrats, but it’s alway the bureaucrats who benefit. The populist right has almost figured this out — that’s why they screech about Communism, when what they really mean is bureaucratic centralism.

Guillem, so noted! Spain had no shortage of alpha-Marxists during your Civil War; unfortunately for them, it had a considerably more robust supply of alpha-fascists.

Leftism in my country is fully kidnapped by wokery since some 10 years ago. From bland socialdemocrats (like our “beloved” Pedro Sánchez President nowadays), to the most fierce (?) Anarchists, they’ve gone all woke. They imitate like monkeys whatever they can hear and translate to Spanish from USA woke universities and “Democrats”. Only a few scattered freaks in the fringe are in dismay with this sad and ridiculous situation alike…I suppose there’s the same s**t everywhere in Western countries. Am I right?

Ok, so you answer focuses in on bureaucratic power and bureaucratic centralism as the specific social phenomenon that Marxism aims to birth and tenderly care for.

That leads to the question of why industrialisation was seen as a necessary part of the process by those you’ve named alpha-capitalists?

And, on that score, is it possible for industrialism to exist without developing a thick bureaucracy? Are these two (industrialism and bureaucracy) inextricably co-joined siamese twins? Or can they exist independently of one another.

@Aurelien

Speaking about Trostki or Stalin’s comunism, i think that in the end we can’t atribute to chance that, wherever Comunism has seized any power, it has always ended up dominated by the Aparatchiks, and not by it’s most “idealistic” members.

For example, when Trotski fell into disgrace, there were people who protested, among them Antonio Gramsci, who was quite influential, but they were not in power, and the leaders lined with Stalin.

To me, that speaks of a way of functioning that promotes such leadership, and made the success of characthers such as Trotski as leaders nearly impossible. JMG explanation, that the real purpose of Comunnism was to industrialize, makes sense in this context.

JMG, you replied to Ben: “In my radical phase I was a democratic syndicalist with some influence from guild socialism via Chesterton and Belloc.”

I have been trying to understand for some years why you write, from time to time, in positive terms about democratic syndicalism, but most of the time keep silent on alternative economic models. Is it that you now seem more flaws in syndicalism than in your youth? Or that you simply see no point in promoting society-wide change?

You also replied to me, with regard to social democratic parties: ” I don’t happen to recall what “selling out and cashing in” works out to in Greek.”

That is not what I was trying to argue. I do agree that the SPD and other social democratic parties have sold out on the working class since at least 2005, if not 1998, if not earlier. However, I do think that, at least from the 1920s to the 1970s, such parties made great strides towards their stated goals: universal health care, affordable housing, some worker control of enterprises (German Mitbestimmung), wider access to higher education, too. Those stated goals did not include revolution anymore. I fail to see where the selling out and cashing in applies (again, referring to the period from the 1920s to the 1970s – there are countless examples from more recent years).

That seems to be something different from the beta-Marxism you define and describe, not least because they weren’t Marxists anymore!

JMG, about Spain and Fascism, the fascists where indeed very useful to win the war, but there is another factor, related to the Communist attitude towards peasants. Franco succeeded in amalgamating his Fascist supporters, wich where small in number but very charismatic and influential, with the rural country-people who did not want communism inflicted to them, thank you very much. With a raquitic discourse he managed to unite very diferent people and won the war.

Prove of this is that, when he took Barcelona in 1939, many of the soldiers where in awe: They had never beheld so big, crowded and industrialized city in his life.

Guillem #34: Communists in Spanish Civil War started to grow in number and power because they were better organized and funded (Stalin rules…) than Socialists and Anarchists. When the war started, indeed, there was a lot of anarchists in the Republican side, but they lost fastly power as their revolution failed, by their own flawns but by state (and commie) repression, too.

@Justin Patrick Moore,

I don’t blame you at all for being attracted to Bey’s ideas. One takeaway I’ve retained from anarchism is that the justifications for authority are almost always transparently phony.

Hierarchy is as natural as breathing and as necessary as oxygen but the only honest justification for it among adults, other than mutual consent, is that sometimes the only way to deal with miscreants is to punch them in the gut until they stop misbehaving and/or moving, whichever comes first, but we can at least be civilized about it.

We all have to deal with hierarchies, but you don’t have to believe their self-righteous poppycock. (And yet, ironically, it’s better if most people do.)

Chuaquin, you’re right. That is to say, the left has been kidnapped and replaced by bourgeois interests.

Scotlyn, alpha-capitalists didn’t pursue industrialism because they valued industrial society as such. They each pursued the industrialization of their own economic sector because they could get obscene profits by doing so. It was only after these individual projects began to interact and weave together an industrial society that bureaucracy on the grand scale became inescapable, partly to manage the inevitable conflicts between industrial magnates and partly because the industrial economy’s harnessing of fossil fuels rendered a huge share of human labor superfluous (Marx got this right) and led to the mass production of new economic specialties to absorb the surplus labor (Marx missed this completely). So the bureaucratic society was the unintended consequence of capitalism. I suspect, for what it’s worth, that the move away from the bureaucratic state toward a renewal of entrepreneurial capitalism is a consequence of fossil fuel depletion — now that the supply of energy is not so extravagant as it once was, a growing share of bureaucratic jobs and exotic economic specialties are no longer needed to absorb a share of the work force, and so the bureaucracies are being pruned.

Aldarion, it’s because I realized through the study of history that economic systems are organic growths, not artifacts, and because I noticed that new economic systems put into place inevitably copy, and often worsen, all the problems of the systems they replaced. I retain a fondness for democratic syndicalism because in certain cases — notably worker-owned corporations — it seems to work tolerably well (and I go out of my way to patronize worker-owned businesses). As for your correction, so noted; I was being snarky. Of course you’re correct that social democracy did accomplish some of its goals.

Guillem, thank you for this. Er, what on earth does “raquitic” mean? I can’t find that in my dictionaries.

Knowing our most esteemed host, I expect this to go in an esoteric direction. I suspect our test subjects, the betamarxes, fail as they violate all of the 4 tenants of magick.

For their spell to coagulate in actually political change, they need to be truly cognizant of the reality of their time, truly motivated by the end goal and purpose of the endevor, willing to exert true force in its deployment and do it under the veil of darkness and silence.

As I see it, all modern movements lack the clarity of purpose, the will of hunger, the agency of action, and above all the humility of discretion. No wonder they fail and will keep do so until they go back to basics.

Charles Radcliffe, one of the founders of the UK SI section, wrote a highly amusing and insightful ground-floor account of how those downwardly-mobile “also-rans of industrial society” went through the 1960s & 70s, flitting from one radical idea to the next radical movement. The book is ‘Don’t Start Me Talking’.

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/1512158.Charles_Radcliffe

As you note, the SI’s penchant for excommunication would reach comical conclusion as they all kicked each other out. “You are no longer a Situationist, you’re just a situation!” Picture the sneer!

Original SI co-founder (and Peggy Guggenheim’s son-in-law) English artist Ralph Rumney (seated mid-right in your SI photo) was turfed out by Debord for failing to submit a written report on time. Heady stuff.

Thanks for the comment about Yeats.

What do you think the purpose of democracy is according to POSIWID?

JMG #44 and Guillem #41

“Raquitic” would a Spanish deformation of “rachitic” (adj) with is the medical term for the rickets in English, aka, “small and misshapen”. It’s kind of funny to use it to describe a speech. Short and borderline unintelligible? Spanish and French speakers will probably all understand but it sounds a little awkward and obscure in English. Arguably a perfect use for the word itself.

@Chuaquin, You are right that Anarchists made a fool of themselves when they took power, but i’ll argue that in a curious sense, they were the opposite of Comunists:

For example, Durruti and his band( as they can’t hardly be described in any other manner) of Militians were brave and capable soldiers, although recognizing that they will never be able to compete in a conventional fight with the professional soldiers on the other side, they fought in a guerrilla style. That brought significant territorial gains in the Aragon front, almost taking Zaragoza…Until the communists enforced a unified and homogenous army, capable of fighting big battles…and lose them. Never again the Republic was able to take and hold any significant piece of land.

So Comunists were way more organized, sure. More, succesful politicians and great propagandists…but bad strategists and mediocre fighters. Yet, they succedeed in hiding all this, and presenting themselves in a favorable manner, while ridiculing their rivals , when they could not afford to attack them openly.

Guillem.

Yes, I can absolutely see that alpha-capitalists, while acting to secure and increase their own profit streams, appear to have backed themselves into the industrialisation of their societies without intending any such thing. (With, as you say “the bureaucratic society… the unintended consequence of capitalism”)

I’m still wondering why, if the bureaucratic society was the INTENDED consequence of the alpha-Marxists, they found industrialisation to be the essential pathway, wherever it had not already taken place? What made them see these processes (industrialisation and bureaucratisation) as such close companions?

Justin Patrick Moore @ 47, I think the purpose of Athenian democracy may have been to give every male citizen, from the poorest thetes, whose job it was to row in the fleet, to the Alcmeonids and other rich families a personal stake in the survival and success of their city. If Athens were to field an effective army, all able bodied men had to serve. Inclusion in government, according to wealth at first, was a way to gain their enthusiastic support. The blood sacrifices were, among other things, a way to keep fighting men well fed. I doubt women were admitted to sacred barbecues. Those rites also would have provided some income and prestige to farmers and herders who supplied the animals.

Speaking of fringe movements, I would like to ask a question of any British citizens here. I keep finding on you tube and other places indications of rewilding parts of Britain, reintroduction of beavers and so on. Also, I notice there seems to be a certain interest in revival of preindustrial craft. How popular are these developments? A growing movement, or just a few eccentrics?

If beta-neoreaction, and the various beta- ideologies on the right serve the same function as beta-Marxism, why then are they not subject to the same “repressive tolerance”? I mean, you can fly the hammer-and-sickle with impunity, you can call yourself a Marxist and chant “eat the rich” on your lunch break from working at at Blackrock or Goldman Sachs… but the minute you step out of line to the right, it’s a different story. Go ahead and call yourself a race-realist in the public square, or hang a Swastika flag on your door. “Tolerance” is not what you’d expect, is it?

So the system does function somewhat differently on towards the left-fringe than the right-fringe. Following POSIWID, I believe it is an important distinction, but I’m afraid I’m not quite sure what it means.

> If a given country repeatedly started wars and lost them, especially if it lost them in the same way every time, then you could apply it. (This offers an interesting insight into the history of Germany.)

I probably don’t need to explain that this isn’t what we Germans learn in school. What purpose do you have in mind? Simply becoming Europe’s punching bag after having Austrians start world wars on our behalf or something deeper?

(I should probably clarify that the dig at Austria is mostly ironic as there’s no way Germany escapes blame for WWII, though our education does seem to suggest that we had rather less to do with WWI than popular discourse would have you believe. Mandy Rice-Davies applies, obviously.)

—David P.

>Some Marxists want to become government bureacrats, others want to bring about a society run entirely by government bureaucrats, but it’s alway the bureaucrats who benefit.

People talk about the Iron Law of Bureaucracy but they never do talk about the Law of Bureaucratic Misery, that every bureaucracy strives to increase net misery in the world. Every single one, whether it’s corporate or government. Corporate ones are constrained by the profit motive, at least in theory anyway, so you don’t see it as often as you do with government.

How did that old Monty Python song go? “You can keep your Marxist ways / But it’s only just a phase”?

YES YES YES! THIS is also my realization-cum-belief and what i’m all about now, but i had no idea that anyone else believed this!!!! and i was starting to accept that i’m likely completely insane.

(smile)

thank you, Papa.

x

——————–

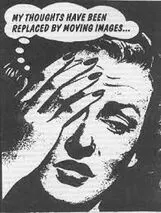

“the Situationists began as an artistic movement that imagined the creation of entire situations for esthetic purposes, and then morphed into a political movement as the political implications of these creative acts became clear….

“….What it was, at its best, was a cogent critique of certain crucial features of modern industrial society (capitalist or socialist) that have not been as clearly recognized anywhere else, and a first tentative sketch of a set of strategies that leverages the strengths of fringe culture against the weaknesses of the established order to expand the possibilities for human freedom. We’ll discuss all this in upcoming posts.”

@47 Justin Patrick Moore

The purpose of democracy is to enable the wealthy to control the government via bribery and control of the mass media, with the sometimes grudging assent of the governed.

The fringes are now accepted on a conditional basis by the mainstrea., because they become a constant source for what the SI calls recuperation… rsw material to be fed vack into the system of spectacularized society.

Man, another cliffhanger:

“a first tentative sketch of a set of strategies that leverages the strengths of fringe culture against the weaknesses of the established order to expand the possibilities for human freedom. We’ll discuss all this in upcoming posts.”

I suppose that I’ll have to tune in next week to find out what happens.

In the meantime, the clueless elite are always the last to know what is happening. The politicians in the EU remain thoroughly wedded to an extreme and irrational ideology (liberalism jumps shark -> woke) eventhough it means death by migrants or death by Russia. The UK is close to imploding/exploding.

The only country in the west fighting the ideology is the US, and the outcome is far from clear. So, I’m eager to hear about these fringe ideas and their dynamics, next week.

Thankfully I lived in a small prairie town so not caught up in this. Hippy on a struggling commune. Delved deeply into Carlos Castenada’s stoned wandering was fringe enough. Since I could not afford university was fairly contemptuous of that crowd as a self defense reaction.

I like the Irish Democracy method of attacking our elite. Low profile OPSEC. Got a lot of hatred for the Covid police state and the smug PMC i need to work on.

@Justin Patrick Moore 47

POSIWID doesn’t have to be completely cynical: the purpose of democracy is to negotiate the peaceful transfer of power, privileges, and spoils among the various elite factions vying for them. The problem is that not just anyone can start a new faction and get a slice of the pie; Trump was in a position to do this because of his wealth and connections but the average citizen is not.

What we’re now seeing is the forced-but-peaceful transfer of power, privileges, and spoils away from the old elite factions to the new elite factions. The old elite factions are not happy about this at all but because we’re a democracy falling back on the traditional method of open warfare risks losing them even the veneer of legitimacy and opens the door to reprisal from Trump’s faction and looting by other factions.

Rashakor, excellent! I hadn’t analyzed beta-Marxism that way, but of course you’re quite correct.

Revelin, thank you — that’s a book I’ll have have to read sooner rather than later.

Justin, the purpose of democracy is civil war prevention. It does this in two ways: first, it gives the politically active sectors of the population some prospect of getting a hearing for their interests in some way that doesn’t require armed rebellion, and second, it provides a means for removing decadent and dysfunctional elites without the same requirement. Since civil war is extremely expensive and disruptive, democracy of some kind is therefore a relatively common condition for complex societies.

Rashakor, hmm. Okay; I considered “rachitic,” but couldn’t make it make sense. It’s as though someone’s speeches were described as oblong, corduroy, and blepharitic.

Scotlyn, Marxist theory requires industrialization. You can’t very well bellow “industrial workers of the world, unite!” if there are no industries and no industrial workers! It’s quite possible to bureaucratize an agrarian society — traditional China is of course the classic example — but it requires a very different mode of bureaucratization than the one that Marxism presupposes and then imposes. So Marxist regimes, once they seize power, always try to launch industrialization programs so that they can have the kind of society they think they’re supposed to lead. Sometimes, as in Russia and China, it works; sometimes, as in many Marxist regimes in the global South, it doesn’t, and then the local Marxist party quietly devolves into a more ordinary autocratic regime, often with a tribal basis, which uses Marxist slogans in place of some more traditional form of totemic symbols.

TylerA, repressive tolerance is only extended to movements that pose zero threat to the status quo. Beta-Marxism is never a threat to an established bureaucratic aristocracy, as it can always be coopted by recruiting successful leaders into the aristocracy (in a nutshell, this is what happened in the aftermath of the 1960s). Beta-fascism is a whole ‘nother kettle of fish, because alpha-fascism is in its element in a failing industrial state. Notice which nations became fascist in the 20th century: in each case, it was an industrial nation hit by a serious economic crisis its ruling class was too incompetent to deal with. The only way for the elites to get ahead of a potential fascist movement is to purge the system of the people and interests who stand in the way of necessary reforms, make a lot of changes in a hurry, get the support of the majority, and use the full repressive power of the state against anyone who tries to push things further in a fascist direction than the ruling interests want to go. That’s what happened in the US after FDR took office in 1933, and it’s what’s happening right now.

David P, I bet that’s not what Germans learn in school! Germany’s problem was twofold. The most obvious problem was that it got much too fond of starting wars after launching successful piratical raids against Denmark, Austria, and France in the second half of the 19th century, didn’t notice that the rest of Europe (above all Britain) had drawn the logical conclusions, and failed to let Austria go hang when the Dual Monarchy picked a fight with Russia. The deeper problem is that it’s essential for the peace of Europe that Prussia never be allowed to unite with any other German-speaking country. Leave Prussia isolated, and Germany can fill its proper role in European culture as Das Land der Dichter und Denker; let it become part of a unified nation, and sooner or later the armies start marching. You’ll notice that the inevitable remilitarization is under way there now.

Other Owen, it’s a valid law. Bureaucracies exist to solve problems, but bureaucracies also have an innate drive to grow. How does an organization that solves problems grow? By making sure that there’s an endless proliferation of new problems to solve, of course.

Erika, good heavens. I didn’t realize that you’d gotten there on your own — I’d assumed you knew you were following in the footsteps of a grand tradition. I’ll consider doing a post on the history of the fusion between the arts and politics in 20th-century Europe — the Dadaists, the Surrealists, and the Situationists were merely the high points in a whole world of artistic politics and political art. In the meantime, if anyone else can recommend some good sources, it should be possible to get you a reading list.

Justin, that’s part of it. Another part is that the fringes are a source of ideas for the aspects of the system that aren’t pure Spectacle — when the system runs up against problems that can’t just be ignored, it sometimes happens that fringe ideas can solve those problems.

Team10tim, the US is shaking off those ideas because the US is not a European society — it has a thin European veneer over the top of something very different, and the veneer is cracking and peeling around us. As for Europe, it was probably inevitable from the start that it would perish from the attempt to follow misguided ideologies straight to utopia.

Longsword, hatred’s a fatal weakness because it makes you stupid. That’s why Hitler lost — he hated his opponents so much he could never measure their strength adequately. That’s why he sent the Wehrmacht into Russia without equipping his troops with winter gear — which you must admit is dumber than the proverbial box of rocks.

I liked Scotlyn’s metaphor of midwife and babysitter! In the same vein, I will say that in the most industrialized countries of Europe, Marxism transformed into something rather different, social democracy, which we might as well call a wife. The industrial economies had to be forcefully convinced to get married (UK and Germany in the aftermath of WWI, France, Sweden and to a certain point the USA in the 1930s), but the marriages turned out to be quite stable and advantageous – as long as the industrial economies maintained their vigour.

When they lost steam (!), when they suffered two heart attacks in 1973 and 1979 and then entered a long period of anemia and consumption, the formerly social democratic parties lost their purpose and direction. They are unable to work productively with a financialized economy, and in those countries where the industrial economy is more dead than alive, the formerly social democratic or otherwise leftist parties are to be had for the bidding.

On the weird synchronicities and affecting politics front: last week I emailed Pierre Polievre and suggested that he take aim the temporary foreign workers programme and the way it is fueling unemployment among Canada’s youth, which has skyrocketed recently. I go on CBC today, and lo and behold! he’s doing exactly that in parliament, making exactly the points I mentioned, and a couple I’d thought of mentioning but didn’t make it into the email.

Cue double-take. I kind of doubt he got the idea from me, or even read my email, but wow. So I wrote another email thanking him, and expressing shock at this having happened.

Don’t know if it will do anything, but at it gets a nasty piece of Canada’s predicament aired in the halls of power and the main page of CBC so the libs can’t hide what they’re up to and it gets more public scrutiny.

This post brings back memories. My experience was a bit like what Steve T. describes. As a political science major at the U of Illinois in Urbana in the 70s, I was exposed to Anarchism and Situationism. There were about 3 other classmates who were interested in the Situationists, although our professors knew about them. The active anarchists were all dropout rabble rousers of the kind that hung around college towns in those days.

After that, I spent some time in Detroit where I got to know editors of a zine called The Fifth Estate. They were supportive of a cadre of old anarchists who had been partisans in the Spanish Civil War. I met some of these old timers at their annual Anarchist Picnic. I enjoyed reading the critiques of society from these sources and thought that syndicalism made the most sense.