Last December’s contest over what theme would get discussed in the fifth Wednesday post, as I’ve noted here more than once already, was unusually lively even by the standards of my lively and eccentric commentariat. What’s more, all three of the leading contenders were themes I wanted to write about anyway. Long before the contest wound up, I’d already decided that I was going to write about all three of them. The first and second place winners, cognitive collapse and the uses of downward mobility as a ticket to freedom, have already had their posts.

This time, accordingly, we’re going to talk about the third place winner, the best and worst aspects of New Thought, that most irredeemably American of spiritual movements, which has been both a significant influence on my own work and a repeated theme of my critiques online and off. “Best and worst” is a good way to approach New Thought teachings, because it has plenty of both. Done right, it can transform your life for the better; done wrong, it can plunge you straight into failure, madness, and death. If that dichotomy catches your interest, climb in and hang on tight. It’s going to be a wild ride.

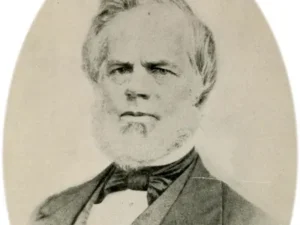

The New Thought movement had its source in the writings of a remarkable New England thinker, Phineas Parkhurst Quimby. Born in 1802, one of seven children of a New Hampshire blacksmith, Quimby grew up dirt poor but rose to comfortable circumstances through hard work and his considerable talents as a watchmaker and inventor. In 1836, a traveling Mesmerist from France named Charles Poyen came to the town where Quimby lived and gave a public exhibition of Mesmer’s methods. Quimby was fascinated, and turned the same ingenuity that earned him several lucrative patents toward the powers of the mind. He became a student of Poyen and followed him around New England, learning Mesmerism as he went.

Mesmerism was itself in the middle of a transformation just then. When Franz Anton Mesmer invented it in the late 18th century, it was a system of energy healing not that different from reiki. The difficulty, of course, is that the Western world from the 1650s on has had a serious allergy to the concept of a life force, which is central not only to Mesmerism but to a galaxy of other healing modalities as well. The great challenge of the time was finding a way to erase the life force from Mesmerism, and that’s how it got turned into hypnotism, the name under which the surviving scraps of Mesmer’s system are known today.

The quest for respectability that drove Mesmerists to refocus from subtle energies to mental suggestion also affected Quimby. After a decade or so practicing the Mesmerism he learned from Poyen, he became convinced that the real source of power in the system was the belief and the attitudes of the patient. He came to believe, in fact, that illness was purely a mental phenomenon, that it existed only because the person suffering from it believed that it existed, and that if he could convince them otherwise, it would go away.

In a significant number of cases, what’s more, he wasn’t wrong. Keep in mind that he went into practice as a healer in Puritan New England during the height of the Victorian era, and most of his patients were middle-class women. The social customs of that time consigned women of that class to a life of decorative uselessness. Excluded from the trades and professions and more often than not denied any but the most basic education, they were also shut out of active involvement in household labor and childcare because of their class—the mark of a respectable family in those days, after all, was that servants did all the real work. Unless they happened to be raised in a family that gave them an adequate education, and turned out to have some talent for one of the very few careers, such as writing, that women were allowed to take up, they faced a life of paralyzing boredom and clinical depression. It’s not surprising that so many of them turned into chronic invalids constantly fussing about their symptoms. It was one of the very few ways available to them to break the intolerable tedium of their lives.

Then came Quimby. With his frank New England manner and his unshakeable self-confidence, he simply sat his patients down, explained to them that their health problems existed entirely in their own minds, and convinced them that they could do something more useful with their lives than languish in bed and complain about their symptoms. His timing was excellent, for he entered into practice as a healer just as women’s organizations for charitable, religious, and (in certain limited cases) political purposes were becoming acceptable options for respectable women. In case after case, women who were considered hopeless invalids before he treated them got up wholly cured, and proceeded to find something more interesting to do with their lives.

One of his patients was a woman named Mary Baker Eddy. She took to the world of religious activities with more verve than most, turned Quimby’s ideas into a theology, and founded the Christian Science movement. Jealous of her role as queen bee of the “mind cure,” she did her level best to deny her dependence on Quimby’s thought, and also developed the habit of expelling successful Christian Science practitioners who might become potential rivals. These promptly founded organizations of their own, and the New Thought movement was born.

A profound ambiguity ran straight through the heart of the new movement, however. Central to New Thought ideology from Quinby’s time on was the belief that every illness, and every other kind of negative life experience without exception, was just as amenable to mental treatment as the psychosomatic ailments of bored and frustated New England housewives. The movement spread so fast and accomplished so much because, in fact, a great many illnesses and a great many negative life experiences can be treated very effectively that way. Time and again, though, the movement and its practitioners kept running up against the awkward discovery that what worked for so many things did not necessarily work for everything.

The reaction to this unwelcome discovery led to a division in the movement—never formal, never total, and very often bridged by teachers and schools who took up positions somewhere in the broad middle ground, but still significant. We can call the two ends of the spectrum thus traced out the pragmatic and the psychotic wings of the movement. On the pragmatic wing, you had those New Thought teachers who recognized that beliefs and attitudes were powerful tools but couldn’t always do the job by themselves. These teachers and the schools they founded taught that proper attitude combined with hard work and a realistic assessment of the situation could work wonders, and far more often than not, they were right.

The teachers and schools of the psychotic wing rejected all this, and doubled down on Quimby’s original postulates. As far as they were concerned, the universe each person inhabited really was a product of that person’s thinking, and could be transformed at will by changes in belief and attitude. The one thing that could prevent this, according to these teachers and schools, was doubt. Absolute faith in the power of the mind was the one non-negotiable requirement of their system. That was where the trap snapped shut on them, of course, because that demand for blind faith made it impossible for them to check their beliefs against experience.

Regular readers already know how that played out, because I discussed it in a post in December of last year. Once you turn your back on reality testing, as I pointed out then, you tumble straight into a close equivalent of the “model collapse” that afflicts generative large language models, the programs miscalled “artificial intelligence” in today’s media. Cognitive collapse, as I labeled the resulting syndrome, causes the mind to drift steadily further from experienced reality into a self-referential world of delusions. This is one of the things that the psychotic end of New Thought methods quite often causes.

The divergence between the pragmatic and psychotic wings of the movement has another dimension, which will inevitably raise hackles in some readers. One of the reasons that Quimby’s methods were so successful in his own time, and did so much good for so many of the people he treated, was that he drew so many of his patients from a disadvantaged group. If you have been taught all your life that you can do nothing, and then encounter a grave and earnest healer who tells you that you can do anything, the most common result is that you will settle somewhere between those two, convince yourself that there are things you can do, and go out and do them. This tends to be very productive.

This tendency to move toward the middle also accounts for the remarkable spread and success of New Thought methods, as well as certain varieties of folk magic such as hoodoo, in African-American communities in the first half of the twentieth century. Once again, a disadvantaged group that had been told over and over again that it could accomplish nothing encountered a set of beliefs that claimed that those who followed certain teachings could do anything. In response, they split the difference and accomplished a lot.

Matters were far different when the same techniques came to the attention of privileged groups. If you grow up being taught that you can have whatever you want, and you then encounter an ideology that tells you that you can get the universe to give you whatever you want if you only have the right beliefs and attitudes, you will likely find that ideology very attractive. Instead of allowing them to find a middle ground that will encourage productive effort, though, the spread of New Thought among the privileged convinced a great many of them that they deserved whatever they wanted and inflated their already oversized sense of entitlement to dizzying levels, with highly unproductive and sometimes disastrous results.

(To head off certain common misunderstandings here, I should probably say in so many words that “disadvantaged” here does not mean “belonging to a group of people that was oppressed a long time ago,” and “privileged” does not mean “assigned to a category it’s currently fashionable to hate.” If your employer pays a significant fraction of your health care costs and you have a retirement plan other than getting Social Security and working until you die, you belong to the privileged classes of American society, no matter what did or didn’t happen to your ancestors. That a good many of the female descendants of those chronically ill New England women are now well up in the ranks of American privilege is just one of history’s many ironies.)

Thus your position in the class pyramid, to a remarkable degree, determines what philosophy it’s wise of you to adopt. For the privileged, something close to classic Stoicism is a wiser choice; the Stoic focus on noticing what you actually control and what you don’t makes a good antidote to the inflated sense of entitlement that so often disfigures the thoughts and actions of the upper classes. For those a good deal further down the social ladder, by contrast, New Thought is a great idea, as it helps them shed the attitudes that keep them from taking charge of their lives and doing something constructive and positive.

Mind you, in most cases people are drawn to philosophies that reinforce their biases, not those that draw them toward balance. This yields another useful litmus test for New Thought: the more it appeals to you, by and large, the less you will benefit from it. If you find the whole idea of changing your life by changing your attitudes silly, or annoying, or self-evidently naïve, give it a try—you’ll likely get a lot of benefit from it. On the other hand, if it seems obvious to you that you deserve whatever you want and that the universe is obliged to give you goodies, stay away from New Thought. It will mess you over.

Those of my readers who have picked up the useful habit of challenging binary divisions will doubtless be clearing their throats by this point and wondering when I’ll mention the third factor that resolves the binary just sketched out into a balanced ternary. (If this is you, congratulations; you’ve been paying attention.) The way from the binary to the ternary in this case can be found by challenging the underlying principle of the New Thought movement, which has been summed up most memorably in the sentence “You create your own reality.”

That isn’t entirely a lie. Instead, like most really problematic ideas, it’s a half-truth. It’s true often enough to convince people that it’s true all the time, and that’s where the worm slips in and leaves the apple rotting outwards from the core. To transform this half-truth to a truth takes only two letters and a bit of punctuation.

You don’t create your own reality, you see; you co-create your own reality. You make an important contribution to the making of your own reality, but there’s this teeny, tiny other thing called the rest of the universe that also has something to say about the matter. How much you contribute to the creation of any particular reality you experience, and how much the universe puts into the mix, varies from one kind of experience to another, but both are always involved.

The concept of co-creation as the principle through which experiences manifest to each of us has a lot to offer all by itself, and I recommend it heartily as a theme for meditation to those of my readers who have taken up a daily meditation practice. To build on that principle, though, I’d like to propose three laws of co-creation which can be tested out in practice.

The first law is this: the closer something is to you, the more you contribute to its co-creation. Your self-image, for example, is very close to you. The attitudes of other people are much further away. You will therefore find it easier to get good results by changing the former than by trying to change the latter. This is reliable enough that I’ve sometimes wondered if an inverse-square law, like the one that governs the effect of electromagnetic radiation, governs co-creative processes.

The second law is this: your actions have as much effect as your attitudes in co-creation. It won’t do you much good to try to make yourself happy by changing your attitudes if you keep on acting in ways that make you miserable. Thus you will get the best results by making sure that your actions and your attitudes align with each other, and with your intended goal. This requires reflection, self-knowledge, and a thoughtfully critical attitude toward your own behavior; awkward as these can be, they will take you a great deal of the way toward happiness and success all by themselves.

The third law is this: co-creation on any plane requires constructive action on that plane. If you want to become prosperous, you can’t do it just by cultivating thoughts or feelings related to prosperity. Prosperity functions on the material plane, and if you want to manifest prosperity, you have to take constructive actioon on the material plane: for example, by reining in your less productive expenditures and finding ways to earn more money. If you want contentment, on the other hand, that’s an emotional state; you can’t achieve contentment by piling up material goods, only by taking action on the emotional plane to become contented with what you have. The same distinction applies to every goal without exception: find the plane on which it exists and act there if you want to succeed.

I quite understand that all of this may be highly dispiriting to those who think they ought to be able to get what they want without working for it, or who are sure that it’s reasonable for them to keep on doing the same things while expecting different results. Nonetheless the universe is what it is, it does what it does, and expecting it to cater to an overdeveloped sense of entitlement is never a good strategy. Learning how to work with it is a much better idea.

One more thing. In this essay I’ve put some needed emphasis on the downsides of New Thought methods. The fact remains that for many people, a good solid dose of the pragmatic side of New Thought can be enormously healing and empowering. It certainly was for me. The specific set of teachings I used to shake up my own attitudes and get me moving toward a more satisfactory life was a correspondence course taught by a Florida businessman turned mystic, Burks Hamner, under the title of The Order of the Essenes. Those lessons can be downloaded free of charge here; the first course, consisting of 23 weekly lessons, is the one I found most useful.

I might very well print off a hard copy of this post and use it for a deeper study. I think it will nicely supplement my Mayan Order lessons. I am also reminded of dependent co-arising within Buddhist thought. I’ve realized as of late I’ve been adopting a basically Buddhist metaphysics without the same world-hating soteriological goal. This might be one more piece of the puzzle for me.

I am also reminded, yet again, of Peter Anspach’s Evil Overlord List: “Rule 22. No matter how tempted I am with the prospect of unlimited power, I will not consume any energy field bigger than my head.”

This was a really interesting read because for some years I was myself ensnared by this self-help nonsense. It took a while for me to understand that these people — Napoleon Hill, Norman Vincent Peale, Maxwell Maltz, David Schwartz, and myriad others — were scammers and conmen.

The best self-help advice I got was from Robert Ringer’s book, “Winning through Intimidation”, where he described how he used to stand in from of a mirror each morning and pump himself full of positive thoughts. The rest of the day he would get the s**t kicked out of him. After six months he realised something was wrong with this kind of positive thinking and also realised that he had to take into account the external world, which had its own rules independent of his desires and fantasies.

I’m an amateur chess player — a rated one, and occasionally playing in tournaments. The first step to getting past beginner level is to understand that what you are trying to do on the board has to blend with what you think your opponent is up to. You have constantly to take defensive and prophylactic measures, interspersed with your own attempts to force your will on the board. Your opponent is the inconvenient external reality.

For a fine expose of Rhonda Byrne’s “The Secret” I can do no better than recommend the following essay:

https://markmanson.net/the-secret

JMG,

My wife and I have what is very close to a perfect marriage ( Knock on wood). But the only real fundamental conflict we have is on the brain or attitudes effect on sickness or health. She had a mother who was something of a hypochondriac. Worries about all illness, medicine needed for everything, hoarded remedies etc. My wife is not this way, but she also does not believe in my attitude that a great part of being sick is mental attitude. I was raised to believe that sickness was for the weak of mind, and those that were trying to get out of work.

Gradually over time our attitudes have come closer together. I accept that certain types of Illness are only slightly improved by mental attitude and she has accepted that many types of illness’s can be improved with a positive mental attitude. We are still not together on this, but we get closer all the time.

I can also vouch for the Order of Essenes material, and the pragmatic side of New Thought in general, which has helped me greatly. The difference in my self-talk a decade ago and now is like living with an entirely different person.

For those downloading the lessons, I’d also like to offer this link, where you can either download the zip file of every lesson as an individual PDF, or have them handily combined into a single PDF for each course. https://octagonsociety.org/archives/order-of-the-essenes/

I’m very happy with this essay. It clarifies some conclusions I had already reached and helps me connect those conclusions with a more systematic outlook. (As a Sagittarius, this is my natural way of approaching whatever I’m trying to figure out.)

Your three laws of co-creation are an elegant formulation. I’ll share this post as it applies to magical ritual in a group I lead.

Deborah Bender

There are sadly many things wrong with the New Thought movement. Mitch Horowitz, a New Thought author who would fall into the middle ground between the two camps, has pointed out that the movement is actively hostile to any attempt to investigate its ideas intellectually even to refine and improve them, and as a result nearly every new book on manifestation is just a rehash of every other, with ideas already stated, and stated better, a century ago.

For myself, my biggest complaint is the way the movement has debased the term “spiritual” to mean little more than “getting goodies.” Not only the intellectual but the mystical side of New Thought has been almost totally left to atrophy. Which is a shame because New Thought of course not only arose from Christianity but some schools have a lot in common philosophically with Advaita Vedanta, Kashmir Shaivism, Yogacara Buddhism, and similar traditions.

P.S. Speaking of Mitch Horowitz, he’s an interesting character in his own right. He’s a theistic Satanist who also makes offerings to the ancient Greek gods, speaks about capital-g God positively, and prays every day at 3 pm Eastern specifically so his readers can join him in a Catholic-style “hour of prayer.”

His con — as you’ve pointed out before, there’s always a con with Satanists — seems to be that he made a hasty vow to God a long time and is now trying to rules-lawyer his way out of it.

It’s interesting that you mention people adopting philosophies that match up with their preconceived notions and stoicism in the same essay. For me stoicism along with the Bhagavad Gita did me an immense amount of good in reducing my worries and overall cognitive load. So imagine my shock when I see a recommended video saying that people misunderstand stoicism. (I think it had a more click-baity title before. Something about it being a loser ideology or something. Not sure.) Anyway, the thesis of the video was that some people were using the philosophy to valourize their already inert life. A lot of people nowadays are living a very Victorian life, living as much of as they can from the confines of their bedrooms. I think some people have come to call it “rot-maxxing.” I guess if you’ve had a tough go at life, a philosopher talking about the capriciousness of the average person would be congenial. Just a damn shame that they didn’t use this philosophy to engage more with life, not less…

By remarkable coincidence I think Jonathan Haidt may have just pointed out the next logical candidate population for another round of New Thought.

In a long article replete with graphs, he argues that “Gen Z as a whole… developed a more external locus of control [i. e., a belief that they are helpless in the grip of forces beyond their control and have virtually no agency in their own lives] gradually, beginning in the 1990s.” He attributes this change to “the loss of ‘play-based childhood’ which happened in the 1990s when American parents (and British, and Canadian) stopped letting their children out to play and explore, unsupervised. (See Frank Furedi’s important book Paranoid Parenting.) I believe that the loss of free play and self-supervised risk-taking blocked the development of a healthy, normal, internal locus of control.”

So if anyone is looking at the L. Ron Hubbard path to wealth (“If you want to get rich, you start a religion.”) you now have the the teachings and the target audience. All you need to do is update the language and develop a charismatic public speaking style.

Brenainn, those rules for evil overlords are surprisingly useful in practice!

AA, granted, but for those people who have never learned to exercise their will on the world, the pragmatic end of New Thought can be genuinely helpful. So, for that matter, can chess — you have to pay attention to what the other player is doing, but you also have to learn to pursue your own strategy.

Clay, and somewhere in the middle is the truth of things. I’ve used a lot of psychosomatic medicine on myself, and gotten a fairly good sense of where it works and where it doesn’t; I can overcome a lot of illnesses using mind power, but not all!

Kyle, thanks for this! I keep forgetting that the OSA has those convenient links.

Deborah, by all means circulate it as you wish.

Slithy, you’ll very rarely find me agreeing with Horowitz on anything, but he’s quite correct here. The abandonment of the mental and spiritual dimensions of New Thought is one of the most heartbreaking things about its history.

Sean-Luc, it’s very much a case of “one man’s meat is another man’s poison” — or in this case, one person’s wisdom is another’s clueless idiocy. It’s sometimes a source of amusement to me that I go through periods where Stoicism helps me a great deal — usually in the wake of grief and pain — and other periods in which the pragmatic end of New Thought is just what I need.

Joan, maybe, but it would take somebody with Quimby’s self-assurance and strong-mindedness to pull it off. My guess is you’re going to see a huge number of Gen Z types making a beeline instead for traditional churches, where they can rest the locus of control in the Christian god.