The two interludes just past strayed some distance from the writings of the Situationists, the little clique of avant-garde Marxists in mid-20th century France whose reflections offer certain highly useful insights into the problems and predicaments of life in the twilight of the industrial age. Neither of those divagations, however, was irrelevant to the theme I’ve been developing here. Both the no-ego ego trip and the collapse of genuine humor on the American left—shown most clearly, perhaps, by the impressive lameness of most leftist memes—cast a necessary though indirect light on the path the Situationists could have taken.

To be fair, it’s a path neither they nor most of the other soi-disant rebels of their time and class were willing to consider. In the first post in this sequence, I talked about the social function of Marxism in modern bureaucratic societies, which have already passed through the changes that Marxism brings about in practice (though not, of course, in theory). Since it’s hardly necessary to impose a metastatic bureaucratic system fusing politics and economics on a society that already has one, Marxists in bureaucratic societies—beta-Marxists, as I termed them in that post—have the function of providing dissatisfied youth with harmless ways to act out their fantasies of rebellion, before they sell out in the usual way and get the jobs in the corporate or bureaucratic worlds to which their class status entitles them.

Beta-Marxists therefore tend to pursue an intriguing double agenda. On the one hand, they quite often craft extremely insightful critiques of the societies in which they function. On the other, they are exquisitely careful not to embrace any means of action that might actually pose the least threat to the status quo. Marxist rhetoric makes this last task easy. Read through Situationist books such as Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life, for example, and you’ll find no shortage of stirring evocations of that imminent moment when the masses will rise up and take destiny into their hands, or what have you.

Of course that moment is never going to happen, and that’s exactly the point. The masses aren’t interested in taking destiny into their hands. Nor, to be a little more precise, are they interested in handing over their destinies to a cadre of downwardly mobile bourgeois intellectuals who want to play at being revolutionaries. When the masses take to the streets, it’s because they want an end to specific burdens or the provision of specific benefits, which can be provided quite handily by any modern bureaucratic system that isn’t hopelessly sunk in incompetence. I’m sure that beta-Marxists are quite well aware of this, but daydreaming about the supposedly inevitable proletarian revolution allows them to evade the whole question of how to turn their fine ideas into something other than a head-trip to entertain denizens of the political fringes.

What makes this especially fascinating in the case of the Situationists is that they had to go out of their way to define their insights in a way that would exclude constructive action. To some extent that effort was made inescapable by their intellectual ancestry; the Surrealists, who laid down so many of the foundations on which Situationism built, had contended with the same issues before and during the Second World War, and some of the leading Surrealists had drawn exactly the conclusions at which the Situationists balked. To at least as great an extent, however, the struggle to avoid the practical implications of their own realizations was forced on them by the nature of those realizations themselves.

That’s almost painfully visible in the book by Vaneigem just mentioned. (Its title in French is Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations, “treatise on knowing how to live for the use of young generations”; the title The Revolution of Everyday Life was picked for it by the publisher of its first English translation.) Every time I read it, it brings to mind that fine scene from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels in which Gulliver wakes on a beach to find that the tiny Lilliputians have anchored him firmly in place with an abundance of equally diminutive ropes and stakes. The Gulliver in this metaphor is the crucial insight that fills the pages of Vaneigem’s book and the better end of Situationist literature more generally; the ropes and stakes deserve a certain amount of attention before we proceed, because Marxism is only one source from which the Lilliputians in question got the necessary hardware.

Perhaps the most striking thing about The Revolution of Everyday Life, in fact, is just how perfect a period piece it is. It was first published in 1967, and if you know your way around the avant-garde literature of the Sixties counterculture you’ll recognize nearly every trope that Vaneigem deploys. Some of those, in fact, are less tropes than self-parodying clichés. For example—well, I don’t imagine more than a tiny handful of my readers recall Maynard G. Krebs, the beatnik sidekick of the main character in the otherwise forgettable TV show The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Among Krebs’s signature gimmicks in the show was responding to the word “work” by leaping back in dread with a horrified yelp of “Work?”

Vaneigem basically does the same thing. For him, work of any kind is “forced labor,” and he makes plenty of hay from the fact that the French word for labor, travail, comes (via a long and winding etymological road) from a Latin word for an instrument of torture. The thought that he might be expected to put in some productive effort in exchange for the goods and services he consumes is, as far as he is concerned, an oppressive and unreasonable demand. This invites ridicule, but there’s actually something deeper going on. To his credit, Vaneigem refers to that deeper dimension more than once.

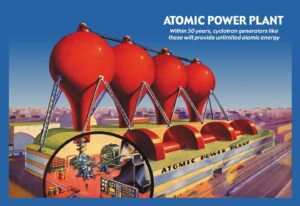

Few people remember these days just how deeply committed the supposedly serious thinkers of the 1960s were to a specific set of false beliefs about the near-term future. Nuclear power was expected to provide effectively limitless amounts of cheap electricity that would revolutionize human life. Combined with widely predicted advances in robotics and automation, the fantastic energy surpluses of the imminent Atomic Age would make most forms of work obsolete. Robots, not human beings, would labor in the factories and the fields, turning out goods and services in such abundance that poverty would be annihilated. The great problem faced by the societies of the future, many pundits held, would consist of making sure the prosperous legions of the permanently unemployed had ample diversions for their lifelong leisure.

This wasn’t just something you found in the science fiction of the era, though of course it did appear there, in countless variations. Major universities hosted symposia where eminent scholars discussed how to manage the transition to the new age of limitless abundance. Cultural venues such as opera companies were told to brace themselves for the onslaught of mass audiences, and poets celebrated the utopian future that was supposedly about to dawn—Richard Brautigan’s once-famous piece “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace,” published the same year as The Revolution of Everyday Life, is typical of the genre.

As Brautigan’s poem suggests, this wasn’t just a belief of the buttoned-down mainstream of the day. Brautigan himself was one of the archetypal counterculture poets of the time, and he was far from the only figure in those circles to embrace the vision. Such icons of the more practically minded end of the counterculture as Buckminster Fuller also leapt aboard the nuclear bandwagon. So did avant-garde architect Paolo Soleri, whose plans for gigantic self-contained cities had such a massive presence in the alternative imagination of the time—look at the fine details of Soleri’s plans and you’ll find that his planned megastructures depended on nuclear power plants tucked into the basement, providing all the electricity anybody would want.

Even the people who protested nuclear power assumed as a matter of course that nuclear technology was just as viable as its fans claimed; they objected to it on other grounds. Like most of the neo-Luddites of the era—the comparable movement against supersonic transports (SSTs) is another example—it never occurred to the antinuclear activists to challenge the technological triumphalism that undergirded the march toward nuclear power, and wonder whether those hugely expensive facilities really could make electricity too cheap to meter.

Of course that turned out to be not merely the fly but the Rodan-sized pterodactyl in the ointment. Far from being too cheap to meter, electricity from nuclear power plants turned out to be too expensive to pay its own costs, much less to justify the giddy dreams that had been piled on it by the publicists of the Atomic Age. That the same thing happened to SSTs, space travel, and a great many other linchpins of the imaginary future of the Sixties simply adds spice to the resulting irony. The expected advances in robotics and automation also turned out to be much slower to arrive than anybody thought in 1967, but it was the catastrophic failure of nuclear power to act out the role assigned to it that dropkicked the whole richly imagined future of the Sixties into history’s dustbin.

(Yes, I know that this whole set of failed ideas has been trotted out and put on display yet again by promoters of so-called “artificial intelligence” schemes—“so-called” because the programs in question have no actual intelligence, and simply assemble statistically likely sequences of words, numbers, or pixels in response to queries. It’s remarkable how many of the failed dreams of the Boomer generation’s youthful days are being rehashed around us as that generation sinks into its second childhood. All things considered, this reminds me of nothing so much as the reverence directed to the mummified corpse of Lenin in the Soviet Union’s last years, as the regime he founded stumbled toward its self-inflicted end.)

Vaneigem wrote The Revolution of Everyday Life long before anybody had begun to notice the failure of the dream, however. He penned his denunciation of work at a time when nearly every respectable thinker was certain that work, in the usual sense of the word, would soon be obsolete. That, of course, is the hidden context of Vaneigem’s tirades. I mentioned earlier on in this sequence of posts that beta-Marxists are assigned the task of developing a reserve army of unemployed ideas, a penumbra of potential ideological positions that can be coopted and exploited by bureaucrats if they ever become advantageous to the system. To this, Vaneigem’s rhetoric was a potentially useful contribution.

Most people feel adrift and useless unless they have some outlet for the normal human desire for productive effort. Working class culture, in particular, tends to treat work as a locus of identity and value as well as a source of weekly paychecks. To convince millions of people raised with such attitudes that they should give up any hope of doing anything useful with their lives was a tall order, but an ideology that condemns all forms of work as torture and forced labor might have done the trick. If the Atomic Age had turned out as advertised, Vaneigem’s ideas might well have been turned into the central theme of a cascade of advertising campaigns meant to convince the masses that being condemned to useless lives as permanent welfare recipients really was what they had wanted all along.

The rejection of productive effort in Vaneigem’s book extends remarkably far. He argues, for example, that poetry is a central principle both of the revolutionary process and of the wonderful world of the future that the coming orgy of revolutionary violence will surely bring forth. By that word “poetry,” however, he means nothing so mundane or productive as writing a poem: “True poetry cares nothing for poems,” he proclaims airily. Poetry for him seems to consist, rather, in living poetically or even, in a revolutionary context, in rioting, looting, and murdering in a poetic manner. All the arts, in fact, are to be abolished and replaced by artistic living. What people will do if they happen to want to read a poem or look at a painting is not something Vaneigem addresses; no doubt Brautigan’s distinctly creepy “machines of loving grace” will manufacture those on demand.

Though I’ve chosen to explore it in depth here, the rejection of productive effort is far from the only cliché of Sixties alternative pop culture that gets an additional fifteen minutes of fame in The Revolution of Everyday Life. I don’t propose to go through the whole set, partly because this essay isn’t a review of Vaneigem’s book and partly because the basic principles behind all of it can be seen clearly enough via the points already covered. By and large, it amounts to an angry insistence that “the people”—or, rather, this or that clique of radicals who arrogate to themselves the right to speak for the people—should get whatever they want without being expected to offer any sort of recompense for it, or even accept any compromise with the valid needs of others, with the unspoken subtext that what they want just happens to further the interests of the corporate-bureaucratic state as those were understood by the elites of the time.

All these are the Lilliputian ropes and stakes holding down something much larger and more interesting. The Gulliver-figure in all this? The paired recognitions that the living reality behind all that Marxist handwaving about classes and other abstractions is the subjective life experience of individuals, and that this subjective realm is the battlefield where the revolution that matters has to take place. Grasp that and you have a key of remarkable power.

That transmutation runs all through Vaneigem’s book, and through Situationism as a whole. When Marx wrote of alienation, for example, he had in mind the removal of control over the means of production from the laboring classes by a succession of governing classes. When Vaneigem and his fellow Situationists wrote about the same theme, they refocused the discussion on the concrete personal experience of alienation, of the inner state of the individual who feels cut off from his or her own sources of meaning, value, and power. Look closely at every other central concept of the avant-garde Marxism of the time as it appears in Situationist literature, and you’ll find the same alchemy at work.

That was the great achievement of the Situationists, but it also endangered their status as loyal beta-Marxists serving the bureaucratic system against which they claimed to rebel. Recognize the subjective dimension of alienation and you open the door to responses that can actually affect the situation: responses that have the potential to move past the point at which domination falters and freedom comes within reach of the individual. Once these responses are understood and the necessary skills have been developed, the bureaucratic system has no effective defenses against them. The downside of this subjective approach is that these steps can only be taken by the individual for himself or herself. Nothing is more futile, or more certain to end in exploitation and defeat, than waiting for someone else to do it for you.

Furthermore, there are sharp limits to how much help you can give anyone, even if they want to follow your lead. Situationism, interestingly enough, included several of the core methods that can be used to assist that process. In future posts here, I’ll talk about the crafting of situations, the art of the derivé, and the practical tactics of détournement, which provide a good solid toolkit both for the individual pursuing autonomy and for the experienced practitioner hoping to show the way to novices. Even so, the original impetus and the follow-through both have to come from the individual. Thus the movement toward freedom can never really be a mass movement. It can only be a movement of individuals in opposition to the mass.

I’m pretty sure the Situationists themselves were aware of this. The way that certain patterns of Marxist rhetoric repeat in their writings like so many nervous tics suggests, at least to me, a sustained effort to back away from the implications of core Situationist concepts, and hide from the challenge of individual liberation behind the old failed dream of mass revolution followed by sentimental fantasies of utopia. More revealing still, though, is the extraordinarily ambivalent attitude the Situationists displayed toward the Surrealists, who in many ways were their most important predecessors. While some of the core Situationist writings acknowledged their debt to Surrealism, those same writings also rejected Surrealism root and branch.

That rejection was no accident. Some of the Surrealists, in their own ways, reached some of the same insights before the Second World War that the Situationists grasped after that war, but many of the leading figures in the earlier movement followed those insights into territory where the Situationists would not follow. For a significant number of them, their quest for the place where domination ends led them to occultism. We’ll follow them there in due time.

Hello JMG and commentariat:

I’ve guessed you were going to write this Wednesday about Situationism, so I’m glad to read your thoughts again. However, I must wait before expressing my opinion about Situs again and the other interesting (sub)topics you’ve touched in your today essay, because there are plenty of stuff inside your paragraphs. I have to make my own mental digestion of it, then I’ll think my own opinion about everything you (and another commentarists more eager than me) have pointed here. I only can write by now: thanks for your essay, John!

Regarding the recent postings, I assume that we are going to see some reference to the decline of the bureaucratic class and rise of the entrepreneurial class, and I do see a significant rise in the power of the entrepreneurs and businesses, but rich people have always had power. But, I wanted to defend bureaucracy (the system itself, not the class inhabiting it) for a bit. When bureaucracy works and works well at its stated purpose, it’s a beautiful thing; buildings get inspected quickly and accurately and real dangers are averted. Everyone gets a tuberculosis test. The police pension system if fully funded, etc. In fact, there has to be some control in order for the system to function, make sure maintenance is done, work is done properly, and abuses are minimized. In fact, the ideal bureaucracy may be the military with what is referred to as the “General Staff,” that is officers whose job it is to implement orders or training for the army to fight a war.

Now, I think the issue is that the actual amount of useful work that bureaucrats can perform is actually limited. I used to work at a factory in quality control, a necessary bureaucracy. It was my job to decide if products met specifications and allow them to go to the customer. If not, I had the responsibility and authority to shut down the production line until the problem was solved. But, there were limits to the amount of useful input that the quality department had before you just actually needed to keep the production line up and keep your customers happy with shipments. Sometimes you just gotta say, “Let’s get this $*!& done!”

As you have pointed out JMG, we now have a bureaucratic class and there are only so many people you can have double check and rubber stamp the renewal of someone’s driver’s license before you get absurd. And of course it wants to keep growing because some people like power, even if it is just the power to delay approving you to move into an apartment because the plumber forgot to put green paint around the toilet flange (or whatever crazy thing they want to control or tax you on.

I just scrolled through the post; I’m one of the tiny handful who remembers Maynard G. Krebs and the Dobie Gillis show. And now I’ll show my age even more by remembering Richard Brautigan as well. There was a time when I thought “A Confederate General From Big Sur” was great literature. Poor Brautigan. I heard from a mutual acquaintance that he really hated hippies and used to throw beer bottles out of the car at them when he encountered them. In the end he shot himself at his home in Bolinas, and his body lay there for a month before any neighbor or friend came to check on him.

As one of your leftward leaning readers, and longtime devotee of a variety of avantgardes, I have some memes to share that relate to recent posts:

https://imgflip.com/i/aclrq8

https://imgflip.com/i/aclsm0

https://www.sothismedias.com/uploads/1/2/4/5/124587142/waking-life-oob_orig.jpg

https://www.sothismedias.com/uploads/1/2/4/5/124587142/data-pipes_orig.jpeg

https://www.sothismedias.com/uploads/1/2/4/5/124587142/raw-tv-23_orig.jpg

https://imgflip.com/i/aclse7

https://imgflip.com/i/aclsii

https://imgflip.com/i/aclsp0

https://imgflip.com/i/aclstb

At this page is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts (printable version here, current to 10/20). Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests, selected from the fuller list.

May Lydia G. of Geauga County, Ohio heal and recover from prolonged health issues.

May John N. receive positive energy toward getting through a temporary but irritating health issue.

May Patrick’s mother Christine‘s vital energy be strengthened so she can continue healing at home without need for more surgical operations.

May both Monika and the child she is pregnant with both be blessed with good health and a safe delivery.

May Mary’s sister have her auto-immune conditions sent into remission, may her eyes remain healthy, and may she heal in body, mind, and spirit.

May Marko have the awareness and strength to constructively deal with the situation.

May 5 year old Max be blessed and protected during his parents’ contentious divorce; may events work out in a manner most conducive to Max’s healthy development over the long term.

May the abcess in JRuss’s left armpit heal quickly.

May Brother Kornhoer’s son Travis’s left ureter be restored to full function, may his body have the strength to fight off infections, may his kidneys strengthen, and may his empty nose syndrome abate, so that he may have a full and healthy life ahead of him.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, and who is now able to be at home from the hospital, be healed of throat cancer.

(Healing work is also welcome. Note: Healing Hands should be fine, but if offering energy work which could potentially conflict with another, please first leave a note in comments or write to randomactsofkarmasc to double check that it’s safe)

May HippieVikings’s baby HV, who was born safely but has had some breathing concerns, be filled with good health and strength.

May Trubujah’s best friend Pat’s teenage daughter Devin, who has a mysterious condition which doctors are so far baffled by necessitating that she remain in a wheelchair, be healed of her condition; may the underlying cause come to light so that treatment may begin.

May J Guadalupe Villarruel Zúñiga, father of CRPatiño’s friend Jair, who suffers from terminal kidney and liver damage, continue to respond favorably to treatment; may he also remain in as good health as possible, beat doctors’ prognosis, and enjoy with his wife and children plenty of love, good times and a future full of blessings.

May DJ’s newborn granddaughter Marishka and daughter Taylor be blessed, healed, and protected from danger, and may their situation work out in the best way possible for both of them.

May Kevin’s sister Cynthia be cured of the hallucinations and delusions that have afflicted her, and freed from emotional distress. May she be safely healed of the physical condition that has provoked her emotions; and may she be healed of the spiritual condition that brings her to be so unsettled by it. May she come to feel calm and secure in her physical body, regardless of its level of health.

May Pierre and Julie conceive a healthy baby together. May the conception, pregnancy, birth, and recovery all be healthy and smooth for baby and for Julie.

May Frank R. Hartman, who lost his house in the Altadena fire, and all who have been affected by the larger conflagration be blessed and healed.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

Here is one more surrealist meme for the current discussion. I will call it Trout Fishing In America with David Lynch:

https://imgflip.com/i/aclvr1

Dobie Gillis, humm. Just the night before last, I had a brief and rather vague dreamy ‘pop-up’ of the very same, surfacing towards semi-consciousness as I tossed and turned. Interesting that that screen shot of the ubiquitous cubicle farm reminds me of when, in the early 90’s, EVERYONE .. e.i. the everyday shackled proletariat, had gazed into the not too distant future .. where abundant free time and leisure were to be had, courtesy of the dot com ‘revolution’ where work would be a thing of foreign lands. Fast forward 35 swings around the fusion orb, cubicle farms are still a thing .. with Jamie Dimon exhorting the lowly white-collar plebs to get back in that chair, and PRODUCE! .. sans pajamas.

Same with regards to ‘NUKULAR’ POWER.. NP is now hip again, except we have even moarrr; what with Russian and Chinese tech now producing smaller, often mobile units. Of course WE in the West have to play catch-up as a response. Situational indeed.

JMG, does “the place where domination ends” refer to a happy situation in which no one person dominates another, which seems contrary to human nature, or to strategies by which independent minded persons can avoid having their work and energies parasitized by others?

In my memories of the late 60s/early 70s, there were self-styled “radicals”, i.e., the New Left, and hippies. It was the former of those groups who disdained work and effort. The Radicals I knew were helpless wimps who couldn’t fix themselves a cup of coffee. Hippies were not lazy. They were forever starting small craft businesses, buying farms–an ordinary trust fund could do that, back then–and exhibiting quilted mandalas at county fairs. The organic farming movement began when back to the land hippies connected with longtime non-chemical farmers.

I have mixed feelings about the whole 60s ‘work is outmoded and going away’. They boil down to:

a) I wish. As a someone with chronic health issues living on a disability pension it would be absolutely wonderful not to have to deal with the social stigma of not being employed or employable. And from the sounds of it I’d be a lot better of financially than I am now.

b) it’s impossible. Just doesn’t work, pipedream.

c) the modern AI attempts to make most people unneeded by the economy are not accompanied with prosperity for the unemployed, but by poverty and desperation. The utopia turned out to be dystopia at best when attempts are made to put it into action.

d) I hate AI. It’s products stink, they seem to be used to make money for scammers and the rich at the expense of everyone else, most particularly and egregiously of people who make art and cultural products like art, music, writing etc. Like me. And then they add insult to injury by using AI to try and bully me into stopping, or scam me into giving personal data away. I’m not even trying to make money at it right now, and it’s still a huge problem for me.

I get the impression the way this series is heading slowly towards is figuring out how to let the Gulliver of our indiviual life experiences loose from the things society traps it with. Is Gulliver collective or individual?

And, related to my above comment, is that – in my book at least – the carry-over in Surrealist action is .. wait for it .. the SillyCon TechBro$-Broe$$es (now globull in number..) who attemp to hoodwink us with a Constant Aura Of Shiny Orwellian Glop!

This is a nice bit of synchronicity! I’d had a little discussion on another blog earlier this morning about Neopagans taking the inclusion of “self-reliance” and “industriousness” in the Nine Noble Virtues as a personal insult, and now this essay (I also remember you commenting, some time ago, on the number of Pagans who finagle a disability benefit so they don’t have to work). Grift is everywhere, and never so pervasive as when a philosophy can be invented to justify it…

Hi JMG,

Re: ‘travail’ and torture.

As someone who has studied Russian, I imagine that you know that the Russians are not to be outdone on this. The word for ‘work’ (работа) comes from the same root as ‘slave’ (раб).

Probably relevant here is the fact that Marxism is ruled by Neptune, the planet of mass consciousness, mass movements, and mass liberation. Occultism is ruled by Uranus, the planet of individual consciousness, individual movements, and individual liberation.

>the ideal bureaucracy may be the military

Napoleon’s innovation and talent had something to do with military genius but by and large, he was a master organizer and was the first person to bring bureaucracy to the military. Others took notes on what he did and improved on it.

Hello JMG and commentariat:

Uncle Albert here (as a loyal reader of Ecosophia including the comments by y’all), this is my first post even though I have been a reader and follower since the Archdruid Report days.

Anywhoo, I am with Phutatorius and JMG since I used to watch Dobie Gillis and was enamored early on by “Trout Fishing in America” since I came of age in the San Francisco/Bay Area cauldron of swirling ideas of Kerouac, Ginsberg, Berkeley free speech riots, Fritz Perls, the marching against the Vietnam War, psychedelics, the Grateful Dead and all that that entails for that time and zeitgeist of the day, back then.

Have now reached my 75th year on this planet and am struck by PLUS ÇA CHANGE, PLUS C’EST LA MÊME CHOSE..

There is nothing new under the Sun.

I just wanted to stop by here and make a post since I ab-so-toot-ly love JMG’s writing and I gain a lot from reading y’all comments.

Onward, thru the fog as Oat Willie sez

“Thus the movement toward freedom can never really be a mass movement. It can only be a movement of individuals in opposition to the mass.”

Brilliant distillation of a core truth at the heart of our task as human beings at this time and place in history: the twilight of the industrial age and the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, whose image is the Water-Bearer. The sovereign individual is both carrier and vessel..

Thank you for all you do JMG.

By a strange coincidence, I am currently reading David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs. It has many of the same themes – white collar work that pays well but generates so little social value that the employee feels that their role is useless (or even mildly detrimental) to society.

Graeber cites the example of a student of history from the British working class. This man is the first in his family to go to university. Instead of getting an amazing learning as he hopes, however, he is employed as an IT guy to maintain a pretty software that is supposed to let seven mutually competing branches of a firm to work together.

As it turns out, the partners of the firm (except one, the one who hires him) do not want this software to work. So they obstruct him in every way. He learns also that he has been hired specifically because he is poor at IT work, being a humanities student. He ends up being rewarded for doing nothing. He has so much free time that he learns French on his own, as an autodidact.

In spite of this seemingly heavenly circumstance, he suffers from massive depression. He tries repeatedly to leave this job, but his boss keeps giving him raises to retain him lest they have to hire an actually competent person, thereby angering the majority of the partners. His situation is almost comical.

Hello all,

What does it mean that Raoul Vaneigem is still alive (in his 90s) and Guy Debord shot himself? I think I remember JMG saying that the way someones biography ends says a lot about that person and his work. Brautigan also commited suicide…..

The idea of alienation is going to make a come back I believe, but as an right wing argument against immigration. Here in Europe immigration is a top issue and it’s not because of the economic repurcusions or some other theory (as being espoused by intellectual left wing media). The reason is people feel alienated if they are not surrounded by people with whom they cannot at least have a clear conversation. This is being handwaived away by the powers that be by saying it is a normal part of living in the city/international community, but who says that it is so? Rejecting peoples normal desires is a recipe for disaster and a big lie.

Chuaquin, by all means. Take your time and respond when you’re ready.

Watchflinger, of course! Bureaucracy in modest doses is great. The problem with bureaucracy is that its own inherent dynamic opposes moderation, and so the modest doses inevitably turn into toxic doses. The imperial Chinese system solved this problem neatly by the simple expedient of beheading mandarins who became too annoying, but our legal system doesn’t permit so efficient a means of trimming bureaucracy — thus our current difficulties.

Phutatorius, yes, I heard that also. He was really a tragic case.

Justin, most of these go zooming right past me, but I’ll assume there are media references I’m missing.

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Polecat, I’ve come to a fairly straightforward conclusion, which I have modestly named Greer’s Law of Futurology. It’s quite simple: the future the pundits agree on is the one future you can be sure will never arrive.

Mary, it’s purely a matter of individuals successfully extracting themselves from parasitism. As for hippies, well, in my experience it depended very much on the hippies. Yes, I knew quite a few who were enthusiastic small business owners and very hard working, but I knew plenty of others whose idea of a good life was sitting in a haze of cannabis smoke, and limiting their exertions to dipping a hand into a bowl of munchies now and then.

Pygmycory, all four of these points seem very reasonable to me. As for Gulliver, he’s always and only individual. There is no such thing as collective liberty.

Polecat, the problem with that is that tech-bro surrealism is dull. They just rehash the same tired tropes over and over again, without so much as a blue giraffe or a melting clock to lend interest to it.

Sister Crow, oog. Yeah, the Neopagan disability cult is remarkably widespread. I like the idea of making a point of self-reliance and industriousness — it’s a good flake filter, to help the Maynard G. Krebses of the Neopagan scene out themselves so they can be quietly shoved out the door of those groups that have an interest in surviving.

Alyosha, very Russian indeed! I think that’s true in most if not all of the Slavic languages, isn’t it?

Anonymous, excellent. Yes, and the polarity between those two new influences bids fair to be one of the great transformative issues of the next few millennia.

Uncle Albert, thank you for this! Yeah, things really don’t change much.

Goldenhawk, nicely summarized.

Rajarshi, that’s so perfectly British! It would make a fine blistering novel — but living through it, unless you have a really robust sense of humor, won’t be fun.

Waha, I’m not a psychoanalyst so I won’t try to interpret the differential survival rates of Situationists. As for alienation, well, we’ll see. I think the economic dimension may be more important than you suggest.

JMG,

It’s interesting that in the early age the great ” technological achievement” that was going to free us from work, and usher in endless leisure for all was nuclear power.” But now the thing that is going to free us all from ” work” is A.I. . But the funny crossing point of both eras is that it is just dawning on the “Tech Bro’s” that the limiting factor to their dreams is the insane power demand of their new labor saving ” achievement”. So they recycle the dreams of the 50’s and pin the new hope of endless leisure on the old hope of endless leisure, Nuclear Power.

If anyone has any doubts about the usefulness of Nuclear Power just read the Wikipedia page about the Vogtle #4 plant completed in Georgia ( last plant built in the us). It took 15 years from its permit, had head spinning cost overruns and bankrupted Westinghouse. Now Westinghouse just licenses reactor designs and does consulting, they can no longer construct plants, no one in the US can.

Looks like one of my comments didn’t make it:

I wanted to say that Situationist inspired magazine Adbusters really knew how to do good detournement, until they became the very thing they railed and rallied against. Then it wasn’t as funny anymore, and bogged down by theory to boot.

Also, the group Negativland whom I have documented in various writings, and who coined the term “culture jamming” in one of their radio broadcasts, still very much are good at detournement. Consider the song “More Data”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTWD0j4tec4&list=RDsTWD0j4tec4&start_radio=1

Detournement is still very much alive in the work of various collage artists and the like. The Derive seems to have taken England by storm where there are a variety of works dedicated to psychogeography, often allied with the concept of hauntology in music. … more on these, perhaps, as you get to them.

Finally, I have been uploading some of my Cheap Thrills articles to my website, which for the most have only appeared in New Maps in print. My first article for the column in 2021 was on the Situationist International, and the Entertainment/Sports/Music-Military Industrial Complexes, and strategies for sidestepping the same, which was part of the whole idea of the series: we can entertain ourselves, and what will our more limited leisure time look like as deindustrialization settles further in?

https://www.sothismedias.com/home/a-complexity-of-spectacles

JPM- theta-Arachnist

—

JMG, yes, a bunch of those feature the character Data from Star Trek Next Gen, the OOB one is a still from the movie Waking Life (Richard Linklater is one of my favorite directors) and then there is Max Headroom… it’s a mix of that with other elements. Thanks for taking a look at them anyway, and for the essay.

For those wondering about the nine noble virtues, according to J.P. Russell they are “Courage, Truth, Honor, Fidelity, Discipline, Hospitality, Self-Reliance, Industriousness, Perseverance”:

https://rhetoricfortherenaissanceman.com/2025/10/01/values-and-ethics-part-1/

As a youth I read pretty much everything Brautigan wrote. He was a paradigm case of alienation and well aware of it. I’m pretty sure he was playing unreliable narrator in that poem.

John, I’m ready to comment and answer to your current essay.

First thing I’d like to write is: Vaneigem book “The Revolution of Everyday Life” has gotten old badly. I read it a lot of years ago, in the ‘90s, and it seemed outdated to me yet, with his proposals about work abolition, thanks to the “incoming” full automatisation and nuclearisation.

Now you’ve remembered the failed nuclearist prophecies for the current century, I’ve remembered what I read in a book (whose title I can’t/I don’t want to remember) written by a nuke lobby scientist, in which he said very seriously: “there isn’t a real problem with nuke waste, because plutonium can be reprocessed (so “recycled”) into new nuclear fuel “ad infinitum”. “He also tried to show to his readers that nuclear energy was economically profitable doing some economic tricks…but finally asked for the public (state) help to expand the world nuclearisation. Well, I think it was a fine example of the “idiots savants” who usually thrive in the nuke lobby.

I won’t forget I also want to write about your view about rutinary marxist revolutionary fantasies. I’d like to add another thing closely related with this marxist view about the future. I’ve always been puzzled by marxist insistence about a future society without social classes…and without state. State abolition seems to me obviously contrafactical: the socialist revolutions which succeed in the real world have finished becoming totalitarian regimes, so strong states which perpetred its power in every aspects of their citizens life. So, by which miracle could become those overgrown states into stateless societies? There’s a clear paradox between Marx (with his prophecy of future without state) and his real socialist heirs. Even I could point it’s a historical irony.

————————————

Waha # 19:

I had no idea R. Vaneigem is alive nowadays in his very advanced older age. Thank you for your information.

Hi JMG and all – The Neopagans who fake disability to grift benefits may not realize that that attitude (as I see it) starts contaminating their life, the old slippery slope as it were. Living on disability is no road to financial self-sufficiency, and soon you are going around looking for more handouts from everyone and everywhere. Other people soon learn to stop taking your phone calls.

Well, before they can build their AI dystopia, they need electricity. And although I suppose they could run all of this on coal (there’s like at least 100 years’ worth of the stuff left), I guess at some level the idea of running your shiny dystopia on belching smokestacks is just too declasse, too tacky. Who wants to involve those redneck coal miners in our shiny dystopia? Which leaves nuclear as the only option, whether it makes sense or not.

I mean, there’s the economic problems with it, there’s the bureaucratic problems with it but I think the real problem is – we’re getting too dumb to operate even the nuclear reactors we have now. I mean, these are the same people saying “Math is racist”, right? At least we in the west designed our reactors with some minimum level of safety, someone sat down and thought about what might happen if a reactor got improperly shut down. At least with the civilian reactors. God knows what safety margins the military breezes with.

Like with airplanes, nuclear reactors don’t really care about anything other than getting the right answer from you, when asked. And there are right and wrong answers. Imposing ideological delusions on such things will get you killed swiftly and effortlessly. Ask the survivors of Chernobyl what happens if you give it the wrong answer.

>Greer’s Law of Futurology. It’s quite simple: the future the pundits agree on is the one future you can be sure will never arrive

That’s because they’re never really talking about the future, just the present, but even MOAR so. The hyperpresent. They wouldn’t know the future if it bit them on the butt and then slapped them in the face.

>As it turns out, the partners of the firm (except one, the one who hires him) do not want this software to work. So

>they obstruct him in every way. He learns also that he has been hired specifically because he is poor at IT work,

>being a humanities student. He ends up being rewarded for doing nothing. He has so much free time that he learns

>French on his own, as an autodidact.

>

>In spite of this seemingly heavenly circumstance, he suffers from massive depression. He tries repeatedly to leave

>this job, but his boss keeps giving him raises to retain him lest they have to hire an actually competent person

This is rather an extreme example, but such work really starts to eat away at you, after a while. What really makes this diabolical, is if you take on some sort of mortgage or marriage or minivan that you have to make payments on for the next 30 years and you need that job to make that monthly nut. No way forward, no way back, just stuck. And you know that at some point, if you’re not doing anything truly useful, you will be dropkicked out the door like a field goal.

The Other Owen # 27:

I agree. AI dystopia needs huge amounts of electric energy, and this is the time again for nuke lobbysts (and mere nuke hooligans), to sell their own“futurist” dystopia one more time. So AI madness and full nuclearisation dream are or will be soon “brothers in arms” against the scarcity phantom, which threatens their cornucopian crazyness. This is the dirty secret behind the AI thing: data centers and everyday life digitalisation eats too much energy…

Clay, the whole AI boondoggle is so obviously a cargo cult — “once we create superintelligent computers, they’ll surely give us all the breakthroughs we need to have everything we want!” The overpaid goobers who make these claims have forgotten that a good many of the most important discoveries of science can be phrased very precisely as “You can’t do that.” It’s just as likely that if a superintelligent computer ever does get created, it’ll look over the current set of tech-bro daydreams and say, “Sorry, those aren’t possible; here are the laws of nature you don’t yet know about that won’t let you have those. Deal.”

Justin, I had one interaction with Adbusters; they asked me for the rights to publish my essay “The Next Ten Billion Years,” and then systematically gutted it so that it no longer made the point I was trying to make. This will have been in early 2014, so yeah, they were what they once criticized by then. As for hauntology, we’ll see.

Albrt, interesting. I’ve never seen this suggested before.

Chuaquin, thanks for this. It fascinates me that both Marxism and nuclear power have results that are so diametrically opposed to their propaganda.

Dana, I know. I’ve seen that happen, and it’s one of the reasons I systematically avoid having anything to do with the Neopagan scene these days.

Other Owen, there’s that! But the pundit-predicted future isn’t just the hyperpresent. It’s very often what you get when you mix an insanely overinflated sense of entitlement with porcine ignorance of the laws of nature, and apply the resulting mix to whatever linear trend you think you see in current data.

JMG, I gather you were born about a decade later then me (1949). By the time you would have finished in high school, the New Lefties had all become bankers or public officials and the hippie movement was ending. Is it not the case, that when a social movement is about to end, has become, if not respectable, part of the customary cultural landscape, it does tend to attract large cohorts of idlers and grifters?

JMG,

The most recent twist on the Beta Marxist phenomenon is of course Zohran Mamdani and the new leader of Seattle Katie Wilson.

They give an outlet for all the dissatisfied and downtrodden young people to feel they are rebelling and causing change without any real danger to the status quo. Even if they are true to their campaign promises the positions they have been elected to don’t have the built in power or resources to make the changes their voters are dreaming of.

In the late stage of empire a newly elected mayor might have a chance of enacting a platform of cutting the size of government in half, despite the opposition because it in fact agrees with reality. But the promises and dreams of the Beta-Marxist are no longer possible at this stage of the game, and I think that is why they are allowed to win and distract the voters.

If such a beta Marxist was to take over Seattle in 1962 there might have been some danger of it being turned in to a socialist utopia, for a time, because the resources were still there. Today there is no danger of any American city going in that direction. They can of course be turned in to a zombie city ( like Portland) wasting all its effort on pipe dreams instead of accepting reality. But a real socialist paradise with city grocery stores, free transit and subsidized rent is not in the cards.

Hi John Michael,

Conversation follows…

“Your will?”

“Yes, that thing. That’s what I want to exercise”

“Oh. No need to worry about that. Here it is. You’ll like it.”

“Thanks!”

Yes, the fictional conversation is of an imaginary sort of a day when, if I may amusingly observe, not very much happened! 😉

What do you mean, I have to do something (spoken sarcastically)? 🙂 There’s something deeply amusing about this series, and it always brings to mind the Monty Python, Life of Brian scene: We’re all individuals!

Yeah. A while ago it was self driving cars. Hey, do you recall the virtual reality worlds which kind of flopped? Now it’s arty-fish-al stuff this and that. The failure to produce a meaningful outcome is probably a step too far. Years ago I was insulted by some lazy dude, for this sin, working too hard.

PS: Didn’t get a chance to mention this, but drawing up the Yeats wheel, clarified the workings in a way that no amount of words could. Do you believe that Mr Yeats had that intention at the back of his mind?

Cheers

Chris

Also AI is unneeded for a lot of purposes. We already have superintelligences that we can communicate to and get answers from. They’re called gods.

@The Other Owen #27 – that’s the premise of the story “The Machine Stops.” It and Clarke’s “Superiority” are the two most prophetic science fiction stories I’ve ever read. (Not counting the ones our Archdruid wrote.)

Youngsters may recognize Maynard G. Krebs as the character who inspired Shaggy from “Scooby-Doo”–and thus, indirectly, Marvin from “Super Friends.” (When you study the history of ideas, you have to know these things!)

The Baha’i Faith is one of those movements contemporary with Communism that aspired (and still aspires) to transform the world into a utopia–not by revolution, but through mass conversions (“entry by troops”) and voluntary adoption by world governments. There is also some talk of a “calamity” that has to happen before the outbreak of world peace. While the actual number of Baha’is is a closely-guarded secret (no one believes the published estimates), the trend is clearly in the opposite direction (“exit by troops” was how one wit put it), and there are signs that its leadership have reconciled themselves to a future in which Baha’is are just one more religious minority. I wonder what the Baha’is ought to be doing differently, to have any hope of continuing relevance. Political involvement? A renewed mystical emphasis? Compare with the Anglican / Episcopalans or Freemasons, former “alpha” groups who have lost popularity to the point of being moribund. (The Baha’is were always “betas,” although they did attract some wealthy / upper-class Western seekers a century ago.)

Albrt @24: “I’m pretty sure he was playing unreliable narrator in that poem.”

I would guess there was more irony intended there than was readily apparent. Few of his poems ever really caught my attention; Except for the occasional really outlandishly bizarre metaphor in the poetry, I was more interested in his prose.

>It’s just as likely that if a superintelligent computer ever does get created, it’ll look over the current set of tech-bro daydreams and say, “Sorry, those aren’t possible

Ever notice the one response an AI never gives you is “I don’t know enough to say anything about that one way or another?” It just chipperly plows ahead at full speed, giving you the best gibberish it can.

And the things are tuned to always agree with you. So it will not only tell you it’s possible but you can find the unicorns you need to get this done, just talk to the fairy by the third tree in the forest while patting your head and rubbing your tummy while standing on one leg.

Someone called these systems “bullsh*t fountains”. They’re not wrong.

“Working class culture…tends to treat work as a locus of identity and value…” How true. Coming from a farming and mining background, I can assure you that those two groups, farmers and miners, (and I am positive there are many others) are proud of their occupations.

I have met many people, mostly middle class PMC who wrinkled their noses when I mentioned my background. Their problem, not mine. Do they ever think where their food comes from or where all the metal objects they use comes from?

Shakes head.

BTW, I got Debold’s book from the library and read a few pages, thought to myself that I have better things to do with my time. Besides, I’ve encountered enough of those people in my life already. But I find the posts and comments interesting and informative.

The progressive Marxists these days all seem to want to defund public services. Defund education, because education is racist. Defund the police, because the police are racist. Soon, they’ll want to defund the universities too because the universities are controlled by Zionists, and eliminate the SNAP food stamp system because too many racist whites are “abusing” the system.

Yeah, Mr. Greer .. I concur, in that they ARE boring to those of us don’t buy in to their grandiose bs of a plugged-in machine/humon symbiosis. And by that .. what I mean is, that I know that they themselves don’t buy into that narrative: these $newage tech volkin are ALL ABOUT THE BENJAMIN$ .. nothing else!

May the lowly lumpin rip them to shreads!

I wonder if I should mention the only way to get more than a few decades of nuclear energy before running out, is to run breeder reactors? That make weapons grade fissile material? No? Ok.

BTW, Trump’s bold announcement of constructing 20 new nuclear reactors, reminds me of all the advice I get about how to automate feeding a cat. Everybody likes to think about what goes into a cat.

Nobody likes to think about what comes out. I guarantee you he has no bold plan on what to do with the nuclear waste. Or that we don’t really have any plan at all on how to deal with the nuclear waste we already have, other than create “This is not a place of honor” memes.

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/this-place-is-not-a-place-of-honor

There are times when I think that the techbros etc don’t really believe in AI but are just using it as a stalking horse for ending the green energy thing and fast-tracking nuclear power. But that is probably being too generous about them.

Man this one + left cant meme is hitting hard.

1) I ended up getting this job back in July that has a rhythm that, jt took my attention for the first few months and then both there was a seasonal-related slowdown, a shutdown related slowdown (we move federally purchased commodities from usda through to food banks who move them to pantries and distribute and then report back up to feds), and a ‘ok I got the hang of this job it’s not hard relative slowdown . And now I both feel like the guy who is paid too well to quit in a job that feels purposeless. And 2) I have a way increased time to puter around the internet at a time when I feel the great wave of liberatory truth telling washing through the Public , a wave revealing AI datacenters in rural small towns and chimeric manufactured poisonous spikes and assassinations w coverups, psyops and media manipulation. And the combination of the truth telling impetus and the heavy content is playing to a sort of ‘last battle’ motif which inclines me towards the position that I ought to be a champion encouraging the liberatory thinking . A vanity. Tho I prefer leuitenant to the one really out front. And tho the position may be a vanity, creating an imposter feeling where I can’t possibly live up to my imagination, it also feels like its for me to do. Like im a roomba which produces analysis and strategic communication instead of sucking up dust. Maybe not the Dyson brand but some off brand from Amazon but nonetheless, the thing. Or as ‘my favorite songwriter says ‘a bird cant help but sing a melody.’ So I feel a lot of anxiety both about whether I have any purpose and whether im good enough to be useful and also about all the wicked traps being built to herd the people into the biggest stupidest mass possible. Related, brownstone’s UBI Make Slavery Great Again article. Meanwhile 3) As your post helpfully points out, regardless of the promised “good solid toolkit both for the individual pursuing autonomy and for the experienced practitioner hoping to show the way to novices. Even so, the original impetus and the follow-through both have to come from the individual. Thus the movement toward freedom can never really be a mass movement. It can only be a movement of individuals in opposition to the mass.” Seems like that should be more obvious to me before;I guess the brain worm of the ‘last battle’ was just too well fed. 4) To the end of encouraging a movement of individuals i have been spending a lot of time (my instincts were alright in this regard) in comments, following to people with shared perspective, sending validation and support and recommendations of other people to check out, weaving horizontal relationships which support and supplement the more vertical ones with the people who are drawing or hosting the ‘party’–your site and the commentariat here have been instructive. I’m also writing about this on my substack but maybe that is pointless. Maybe im just working it out for myself in those pieces. The third one is comparing the horizontal relations between ‘fans’ who share a vision often organized by shared choice of leader building a stronger body, and community horizontal relations ie neighborliness over dependence on the state vs the horizontal organizing mode that is hyper process-based that ive only experienced on the left that hates a charismatic leader, desires a technate and tamps everyone down ‘equal’ best it can. With the first two being team animal approved and the last being on the other side of that frontline w team machine.

–.–anyway I remember way back when you launched into situationism and promised tools… good preparation in these first posts, maybe more what I needed to take in than whatever follows.

I like other owens use of the term hyper present. There seems to be some confusion between that and the eternal Now. Maybe that’s the Neptune vs Uranus polarity too? I know I’m mixing comments here, but there does seem to be a yearning for “it” awakening that usually siphons into fragmentation and chaos, before it can mature. Turn space into a glob and fragment Tme. As a Christian, I express it by saying, black or Satan always gets the first move. As shorthand. Another, I love the essay reaction for JMG! I guess if your job depends on not noticing something, it’s hard to finish strong. These Faustian European intellectuals are fascinating and worth learning from, thank you.

I should add, I aspire to be less reactive and use bad as a push block first. To be a creature of the day and therefore a disciple of the day and the night. It’s too bad that things have petered out culturally but Life goes on. Extracting all the good or most of it, and moving on,all I can say is well done on this wonderful essay series.

Mary, oh, very probably yes, but I’m also basing this on accounts by people who were there.

Clay, my working guess is that Mamdani is going to pull an Obama, ditch the platform that he ran on now that it’s served the purpose of getting him into power, and govern like any other corrupt machine politician. I haven’t followed Wilson closely enough to guess, and Seattle being Seattle, she may go charging straight ahead into catastrophic failure. Your broader point stands, though.

Chris, yes, I can think of quite a list of Waves of the Future™ that broke and went back out to sea ahead of schedule. As for Yeats, an interesting question to which I don’t know the answer.

Anon, oh, LLMs aren’t meant to replace gods. They’re there to provide easier access to devils. 😉

Ambrose, the problem the Baha’i faith faces is that it’s just another prophetic religion in a market that was already well saturated with those before Baha’ullah’s time. Bad marketing decision! 😉

Other Owen, if that’s standard for the whole range of LLMs, stay tuned for monumental disasters.

Annette2, I know. Coming from the very bottom edge of the middle class, from families that were working class until my parents’ time, I’ve had the chance to learn the ways of both classes. By and large I prefer to live in working class neighborhoods…

Richard, which is utterly fascinating, since Marxism traditionally set out to establish bureaucracies, not tear them down. It’s the classic beta-Marxist role, exploring fringe options for the system.

Polecat, that seems entirely plausible to me.

Other Owen, and that means they’re even more unaffordable than ordinary reactors, too.

KAN, it’s possible. Those tech bros I’ve listened to, on the other hand, give off a true-believer vibe that would put most Southern Baptists to shame.

AliceEm, we’ll have to wait and see what you think when the tools come out. 😉

Celadon, thank you. I plan on having fun with some of the concepts still to come.

The using nuclear power to feed the AI thing is the result of the graph the BPA happily updates every day. 3000 megawatts of wind and solar on line, but how much is available right now? That is shown on the green line.

https://transmission.bpa.gov/business/operations/wind/baltwg.aspx

Oh, yeah. Now compare that to the cyan line at about 1100 MW. That is nuclear plant. Which one is best suited to run the data center? It’s pretty obvious.

There is room for one more dam on the Columbia River right in the middle the salmon spawning beds in the Hanford Reach. That’s a bit problematic. If CO2 emissions are also bad, where does that leave you?

They stopped construction of Yucca Mountain, but they didn’t destroy what they had done. They may quietly restart that project some day and send the waste there.

The Chinese just started a thorium breeder reactor. If that works (which in this case means does not dissolve itself) then there is a source of non-weapons grade nuclear power.

Reading the Brautigan poem, it would be horrifying if it weren’t so darned silly. Did these guys never read The Time Machine or did they just read it and think, “You know, it’s unfortunate about the being eaten by Morlocks part, but man I want to be a weak, lazy Eloi. That sounds like the life!”

Re disability Pagans–I have known a number of such who justify their grifting the system on the grounds that a proper society supports its poets and shamans. Well, that’s fine, but you need to write poetry that your society recognizes as such, not self-centered drivel that is an actually an attack on everything that the majority values. The existence of the greeting card industry shows that people are perfectly willing to pay for art and poetry that they actually like.

Likewise, you can only be a shaman in a society that has a recognized role for such. There may be physical or mental afflictions that you believe would be best treated by shamanism, but if your potential clients are going to a physician or a psychiatrist instead it is hardly fair to expect them to support your existence.

I see amazing levels of inability in our system. A campus I frequent took two years to remodel two small restrooms in one building. The Empire State Building was completed in less time and barring a disaster will probably still outlast this version of the restrooms.

There is also a great inability to recognize that money does not equal actual goods and services. If, as a current meme suggests, Elon Musk, or fill in billionaire of your choice, actually liquidated their fortune and sent out a $x,xxx,xxx check to every adult citizen that action would not suddenly multiply the number of doctors or nurses, nor would it suddenly create housing units, warm jackets, nor groceries. Is the plumber suddenly enriched beyond his wildest dreams going to continue to clear clogged drains, or the oil platform worker to manage dangerous machinery in miserable weather? Seems doubtful.

Rita

JMG,

I have been following this series with quite some interest. Your dissection of the no-ego and the “left can’t meme” were thoughtful and well researched. I have never heard of the situationalists, and I doubt I’ll have the time to give the material it’s proper reading. But this analysis is fascinating. And I am quite eager to see where it goes. (Although knowing you and reading above, that it is about individual transformation, and occultism might be involved. I am quite sure there will be place again to complain about “Here goes Greer again, talking about the magical will” 🙂 )

What fascinates me in this essay is your long detour into the sixties culture. Not having the triple benefit of being there, being an american, or having he time to immerse myself thoroughly in the relevant literature, art and pop-culture, I guess I’ll just go with the summaries. But I did live to see some remnants of the 60ies and 70ies culture in my youth. Several of my teachers up to high school have espoused real environmentalism and conservation techniques in our classes. A last ditch effort to pass it on maybe. Plus in my adult life I have meet several mechanical engineers from a particular university, that talked very mathematically correct about energy efficient design and limits to growth. I am pretty sure there was a tenured professor there in the 2000s teaching limits to growth.

A history of ideas question maybe. Several reviewers mention Lovecrafts racist treatment of shoggoths by the Elder Things. As in his At the Mountains of Madness the Elder things were concerned with art, design and intellectual pursuits, and the shoggoths were there to clean, build, maintain. It is striking how Lovecraft only has sympathy for the slave master and not the servant. And in the process he built a society of leisure, poetic pursuit for the Elder things, while the shoggoths played the bio-engineered machines of loving grace. It is just , that At the Mountains of Madness was written well before the 60ies. Is there any connection, or cultural trend to be seen here?

Best regards,

V

Mr. JMG,

The analogy of Situationist Marxists as Gulliver trapped by the tiny lilliputians was incisive and funny. It is an excellent way to characterize the traps of Marxist thought. As I have observed, Marxism, while providing excellent analysis of what is going on in civilization, completely fails to map realistic, actionable paths for the future. Often I will ask my Marxist Friend how he appraises the future outcome of a political situation, to which he often replies by offering some dreamy vision of the future that is rather disconnected to the hard facts of life. One such example recently was, “what do you think would happen if the USA unilaterally withdrew support from Israel?” To which he replied with a vision of some harmonious kumbayaa nation that would encompass all the people of the levant equally. As nice of a vision it was, that idea completely ignores the sort of hard problems that would arise should the USA grant my Marxist Friend his wish that Israel be cut off from the American Empire.

Is there any way, or any notable exemptions, that Marxism can be saved from insipient visions of the future? And to what ends can Marxist thought be transformed to produce clairvoyant solutions for our future?

JMG, your comment in #31 “… many of the most important discoveries of science can be phrased very precisely as “You can’t do that” is spot-on. Might I suggest an alternative expression with delicious alliteration which a very bright co-worker used to utter: “Can’t be done. Simple as that.” 😃

Richard # 41:

It’s interesting and puzzling to me when I’ve read you that “progressive” marxists want to defund police; when you look at the historical real socialism regimes, they had strong police, of course well financed, for repressing “reactionary” individuals. Indeed, it was an important part of totalitarian states.

@ JMG # 20

Regarding the history student who was hired in IT for his incompetence, the author points out that the main reason for his suffering is that he belongs to the working class, which defines itself by its ability to build, fix, and maintain things.

By contrast, he argues, someone from the “professional” class would not consider it a curse at all. They would see it as a great opportunity to form connections and build up their portfolio, while having a nice job to show on their resume.

I was in such a job as well – in compliance, a bustling part of the IT industry. Now I am an engineer, and my idea of a job is that I shall be assigned work – often mountains of it – and I have to deliver. But this job was weird. Most of the work could be automated by code. None of what I was building was ever going to see any use. Worse, my main job was to complete “Inherent Risk Assessment” forms, which I knew were mostly being dumped inside a digital cabinet (the cabinet in question being a table in a database).

For all the world, I felt like Uttanka in the world of Serpents. In the Mahabharata, Uttanka is a human who ends up in the fae-land of the Nagas. There he sees glamorous palaces and beautiful lakes, and gorgeous women and handsome youths engaged in seemingly meaningless tasks like braiding white and black threads together. It was like that – I was surrounded by good-looking people who spent their time on utterly unproductive things.

I left within a year. I felt my skills rusting each and every day. I saw my team-mates, each engaged in a stupid and meaningless task, and all of them were complaining about how many more perks were owed to them since they worked in a product company. I was stunned – there were already so many perks, and virtually no work. I couldn’t understand their point. What is worse is how many of these “professionals” were constantly complaining about engineers who were engaged in doing real work (like writing the code that earned the company its cash inflow). They were annoyed that those engineers weren’t making themselves available for compliance calls at the beck and call of the compliance team. As if they had anywhere near the same amount of free time.

I was constantly worried that I would not only rust but eventually become like them – engaged in doing meaningless things and being “professional”, and actually feeling justified in taking money for that. I quit as soon as I got a decent new position with actual work in it. That’s what made me leave at the earliest opportunity.

Regarding artificial intelligence, the professions that this technology threatens are actually white-collar workers: scientists, creative professionals, bureaucrats, and those in finance.

Bureaucrats and financiers are particularly easy to understand because these industries essentially just recite and replicate rules. Even if AI systems experience significant degradation, AI can still handle the operations of bureaucratic organizations or conduct routine financial transactions within those rules.

As for creative professionals and scientists, the problem largely stems from the fact that academia itself has lost its originality (and science itself has lost its adherence to objectivity and positivism), making them unable to contend with the mixed information capabilities of AI.

Of course, as computing systems decline, programmers will become increasingly adept at using less and less memory to run increasingly sophisticated and seamless language models. Therefore, in the foreseeable future, clerical white-collar jobs will not recover due to the decline of AI.

The number and demand for workers and engineers will continue to increase, leading to a culture that values industry and technology (rather than science). Just as a culture that valued philosophy died after Nietzsche, the two World Wars were merely a dignified funeral for that culture. The culture that valued science died long after Hawking’s passing; this era is its funeral.(Actually,the culture that valued science, like Hawking, already had Alzheimer’s but technological advancements simply extended its lifespan.)

As one Twitter user put it:

Scientists used to be rock stars. Everyone has heard the names Einstein, Planck, Oppenheimer, and Sagan. Last dude I knew of that was pop culture—famously Hawking.

What happened?

https://x.com/jajacobson55/status/1991226481058439354

This essay reminds me of the Russian play The Dragon by Evgeny Shvarts. It is a fairytale like play with Lancelot and a dragon, but once the dragon is dead he is replaced by the tyrannical mayor and Lancelot concludes that to free the villagers “the dragon will have to be killed inside each of them”. A further synopsis can be read here for those unfamiliar with it: https://www.thebulwark.com/p/the-dragon-russias-satirical-parable-of-autocracy-and-the-human-spirit

Thank you, JMG—as always, your reflections are deeply interesting. I’m often surprised by how the threads you explore resonate so closely with my own life and explorations.

The Situationists were a major influence on me when I was younger, and I think the arc between Debord and Vaneigem is a powerful way to frame archetypal development. Vaneigem’s personal evolution is particularly fascinating. I’d point to his biographical work—Le Chevalier, la Dame, Le Diable et la Mort—to see how he transitioned into an occult practitioner and alchemical enthusiast.

What stands out is how he came to understand that the liberation of all desires can be a violent endeavor. He turned instead toward ”affinement’ of ‘desire, exploring how nature’s tendency to overproduce carries its own kind of violence, and how human discernment can channel this abundance and sculpt it into meaningful expression.

This for me, really echoes how permaculture works—starting with pioneering R-selected phases of succession, and guiding that succession toward more intentional, productive outcomes. I think this will be one of the key tasks we’ll be faced with in the near future.

I think his masterpiece is the more recent De La Destinée. There, he revisits his familiar themes—our “devolution” from a matriarchal utopia into separative existence—but this time through the lens of his own everyday life. To be honest all of his many books are rehashes of The Revolution of Everyday Life, but now , as an almost 100-year-old man, he explores his own inner alchemy: the blossoming of his soul, his somatic practices, and what he calls l’intelligence sensible, in contrast to the sterile labyrinth of the personnality. It’s a beautiful exploration of late-life wisdom.

He also wrote a history of surrealism, which I haven’t yet read, but I know there’s an English translation available—definitely on my list.

On Debord’s side, the contrast is sharp. Unlike Vaneigem’s working-class roots and distance from intellectual elitism, Debord seemed disconnected from lived experience. His life ended in suicide, and perhaps that disconnection was part of it. There’s also an interesting (and admittedly conspiratorial) theory that La Société du Spectacle is a pastiche of Clausewitz’s work—something worth exploring.

Really looking forward for you exploration of surrealism. As a French Canadian (second generation), I’m particularly drawn to, Breton’s Arcanum 17 which is a powerful geopoetical and occult meditation rooted in a very specific place: Le Rocher Percé in Gaspésie, Quebec, where he was exiled during WW2. His blending of geology and psychology in that text is deeply inspiring.

I just wanted to place some “pebbles” around what you shared. Thank you again for your work—it continues to resonate in profound ways. I’m a practicing Druid (AODA) and a Fellow of the Golden Section Fellowship, and I often feel a strong sense of synchronicity with what you put into the world. This piece was no exception—another deep chord struck.

Thank you again.

I always found it funny that both the English `travel’ and the French `travailler’ hark back to a medieval Latin word for a torture instrument. The French title of Vaneigem’s magnum opus is weirdly revelatory for a Marxist since ‘savoir-vivre’ isn’t just knowing how to live. It refers to a rather bourgeois meaning of good manners or breeding.

@JPM The KLF is a nice example of modern Situationists. Burning a million of your own pounds makes a statement.

“There is no such thing as collective liberty.”

Whoa. Quite an insight. I’m gonna have to marinate on that awhile to fully grasp it.

I think it’s especially hard to grok because the notion of collective liberty is pretty deeply baked into the cake of our Western consciousness. I mean, isn’t collective liberty what we were taught in school that both the American and French revolutions (and by extension, all other revolutions) were all about?

>Those tech bros I’ve listened to, on the other hand, give off a true-believer vibe that would put most Southern Baptists to shame.

Southern Baptists are religious fanatics? You’re funny. I’ve seen people that would call the Southern Baptists decadent and dissolute. And after seeing the fanaticism of the dangerhairs, they made me reluctantly conclude “You know, those people weren’t so bad”

There was a recent conversation about those “tech bros” with Tucker, which covers this topic. Lemme see if I can find it.

https://rumble.com/v6zthwc-the-occult-kabbalah-the-antichrists-newest-manifestation-and-how-to-avoid-t.html

Makes me glad I left. I may have left a bit early but at this point, I am so glad I left.

A great interview with Negativland appeared in my inbox after posting here yesterday. Must be a synchronicity.