Now that the preliminaries are out of the way, it’s time for us to plunge into the depths of Yeats’s Vision. That’s easy, in a certain sense, because Yeats starts out the main body of our text by tossing the reader straightway into the deep end of the pool, launching at once into the core images that undergird his magical philosophy. In another sense, of course, that’s exactly the difficulty, because it’s all too easy to land with a splash in these waters and sink without a trace. My goal here is to hand out life jackets and so make that initial plunge a little less risky.

“A little less risky” is the crucial point, though. We are going to cover a great deal of ground in this essay. Most of it will be much clearer when we’ve gone further and sorted things out in more specific detail. For now, do your best to follow along, read every paragraph here at least twice, and give the relevant section of A Vision—the first section of Book I, titled “The Principal Symbol”—several close readings. Yeats was not in the business of coming up with a little light reading for the clueless. He was trying to explain a profound and important way of looking at the world, with deep roots in occult philosophy.

Notice, to begin with, that I mentioned the core images that provide A Vision with its foundation, not core ideas. It’s crucial to grasp this, and not just for our present purposes. One of the primary differences between occult philosophy and the more respectable branches of philosophy is precisely the distinction between image and abstraction. A quote from Dion Fortune’s The Cosmic Doctrine is apposite: “In these occult teachings you will be given certain images, under which you are instructed to think of certain things. These images are not descriptive but symbolic, and are designed to train the mind, not to inform it.”

That quote applies with equal force to A Vision, and there’s good reason for the similarity. Fortune penned The Cosmic Doctrine in 1923 and 1924, while Yeats was writing the first version of A Vision; like Yeats, she was working from material received in trance via a magical partnership—her relationship with her longtime friend and fellow occultist Charles Loveday apparently didn’t extend to sex, but the two were very close and were buried side by side in a Glastonbury graveyard. Of course Yeats and Fortune also shared the same occult background: both had traveled, like so many other occultists of their day, from Theosophy to the Golden Dawn and then to an enduring fascination with Celtic traditions. Working within a common tradition as they were, it comes as no surprise that they used the same method to communicate their insights.

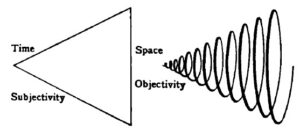

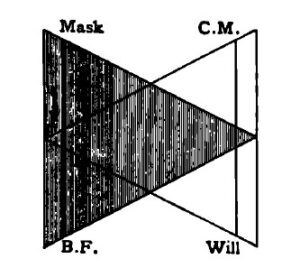

Yeats begins, therefore, with the image of a vortex or gyre. Think of a tornado or a waterspout, with one end contracted to a point and the other at full expansion. Now imagine a triangle, to serve as a schematic image of such a vortex. Lay it on its side, as shown below on the right. Get used to this image—you’ll be seeing it a lot. Remember that it’s a vortex, not simply a triangle.

As our text points out, a single vortex is one way to diagram the relationship between the two opposing principles Yeats has in mind, which are the subjective life—meaning here a person’s experience of himself or herself—and the objective life—meaning here a person’s experience of everything that is not the self. The subjective life extends in time: if you watch your inner experiences you’ll encounter a constant flow of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, forming a sequence along the one dimension of time. If you pay attention to the world around you, you’ll encounter a great many things simultaneously present in the three dimensions of space. Thus the point at one end of the vortex represents time and subjective experience, and the whirl at the other end represents space and objective experience.

As our text points out, a single vortex is one way to diagram the relationship between the two opposing principles Yeats has in mind, which are the subjective life—meaning here a person’s experience of himself or herself—and the objective life—meaning here a person’s experience of everything that is not the self. The subjective life extends in time: if you watch your inner experiences you’ll encounter a constant flow of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, forming a sequence along the one dimension of time. If you pay attention to the world around you, you’ll encounter a great many things simultaneously present in the three dimensions of space. Thus the point at one end of the vortex represents time and subjective experience, and the whirl at the other end represents space and objective experience.

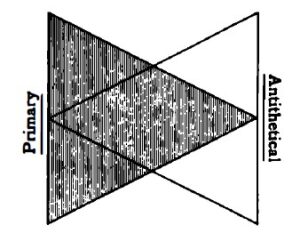

Yet people differ in their relationship to these two kinds of experience. Some face outward toward the world of objective things in space, some face inward toward the world of subjective things in time, and some—a smaller number—are torn between these two. The people who face outward Yeats considers representative of what he calls the primary tincture, and those who face inward similarly represent the antithetical tincture. In our text, rather than a single cone, these two options are symbolized most often by two vortices or cones, each with its point in the center of the other’s wide end.

Yet people differ in their relationship to these two kinds of experience. Some face outward toward the world of objective things in space, some face inward toward the world of subjective things in time, and some—a smaller number—are torn between these two. The people who face outward Yeats considers representative of what he calls the primary tincture, and those who face inward similarly represent the antithetical tincture. In our text, rather than a single cone, these two options are symbolized most often by two vortices or cones, each with its point in the center of the other’s wide end.

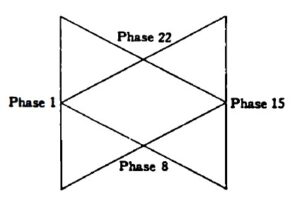

This is the most basic symbol of the system: two cones or vortices facing in opposite directions, each growing as the other shrinks and shrinking as the other grows, “each living the other’s death and dying the other’s life.” Imagine a vertical line slicing through the paired triangles, moving first from left to right and then back from right to left. When all the way over to the right, the primary cone will have dwindled away to nothing and the vertical line will be for all practical purposes pure antithetical; when all the way over to the left, the antithetical cone will have dwindled accordingly and the line will be essentially all primary. At any point in between, there will be some different proportion of primary to antithetical orientation, more antithetical on the right side of the diagram, more primary on the left side, exactly balanced in the middle.

This is the most basic symbol of the system: two cones or vortices facing in opposite directions, each growing as the other shrinks and shrinking as the other grows, “each living the other’s death and dying the other’s life.” Imagine a vertical line slicing through the paired triangles, moving first from left to right and then back from right to left. When all the way over to the right, the primary cone will have dwindled away to nothing and the vertical line will be for all practical purposes pure antithetical; when all the way over to the left, the antithetical cone will have dwindled accordingly and the line will be essentially all primary. At any point in between, there will be some different proportion of primary to antithetical orientation, more antithetical on the right side of the diagram, more primary on the left side, exactly balanced in the middle.

(Take a moment to go over the previous paragraph an extra time or two and make sure you have the image in mind: the two triangles, and the vertical line sliding back and forth from one side to the other. That will help you understand what follows.)

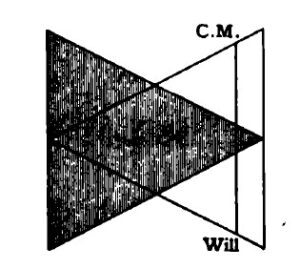

The two basic faculties of human consciousness, in Yeats’s system, are Will and Creative Mind. Will could as well have been called Desire or Energy—it is the faculty in each of us that seeks to express our own sense of what should be. Creative Mind could as well been called Perception or Consciousness—it is the faculty in each of us that seeks to experience the world exactly as it is. The Will is antithetical, while the Creative Mind is primary.

Now think of that vertical line sliding from one end of the two-cone diagram to the other, and back again. One end of that line is the Will, the other is the Creative Mind. When the line slides most of the way over to the antithetical side of the diagram, the Will is strong and the Creative Mind is weak; a person in this condition pays little attention to what is, and throws all his or her energy into creating what he or she thinks should be, whether this takes the form of art, politics, or what have you. When the line slides most of the way back the other direction, the Creative Mind is strong and the Will is weak; a person in this condition focuses intently on what is and ignores thoughts of what he or she thinks should be. When the line is in the middle, the person is torn between these two alternatives.

Now think of that vertical line sliding from one end of the two-cone diagram to the other, and back again. One end of that line is the Will, the other is the Creative Mind. When the line slides most of the way over to the antithetical side of the diagram, the Will is strong and the Creative Mind is weak; a person in this condition pays little attention to what is, and throws all his or her energy into creating what he or she thinks should be, whether this takes the form of art, politics, or what have you. When the line slides most of the way back the other direction, the Creative Mind is strong and the Will is weak; a person in this condition focuses intently on what is and ignores thoughts of what he or she thinks should be. When the line is in the middle, the person is torn between these two alternatives.

(Again, take a moment to reread this and think through it.)

Each of the two faculties we’ve discussed has an object, another faculty on which it focuses. The Will’s object is the Mask. It has this name because, as we discussed in relation to the essay “Per Amica Silentia Lunae,” the Will always seeks its opposite: in order to create, it puts on a Mask that is as far from its natural habits as possible. The Creative Mind’s object, in turn, is the Body of Fate, which can be thought of as the sum total of the circumstances that make up life. In Yeats’s system, just as the Will and Creative Mind can be seen as the two ends of a vertical line sliding right and left across the diagram, Mask and Body of Fate are represented by another vertical line that moves together with the first line, but in the other direction.

So the basic diagram of one type of individual is as shown here. The line representing Will and Creative Mind is exactly as close to the antithetical end of the diagram as the line representing Mask and Body of Fate is from the primary end. As the two lines slide back and forth, moving further away from each other and then back together, each going all the way to one side and then all the way to the other, they define certain typical human characters and situations. Each person is at one or another point in this cycle, and that point, for convenience, is defined by the placement of the Will.

So the basic diagram of one type of individual is as shown here. The line representing Will and Creative Mind is exactly as close to the antithetical end of the diagram as the line representing Mask and Body of Fate is from the primary end. As the two lines slide back and forth, moving further away from each other and then back together, each going all the way to one side and then all the way to the other, they define certain typical human characters and situations. Each person is at one or another point in this cycle, and that point, for convenience, is defined by the placement of the Will.

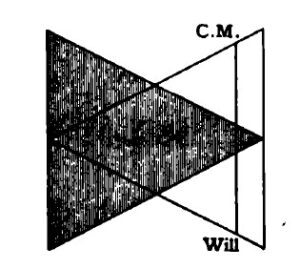

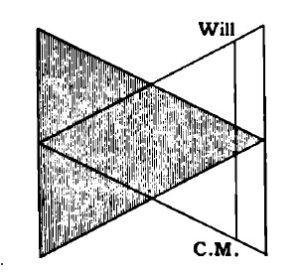

There’s one other wrinkle that has to be understood to make sense of all this. When the line indicating the position of Will and Creative Mind is sliding from right to left (and the other line, indicating the positions of Mask and Body of Fate, is sliding from left to right), that’s one kind of experience of life. When the two lines are sliding in the other directions, that’s another kind. If the Will is growing stronger and the Creative Mind fading out, that leads to a very different kind of life than when the Will has achieved its goal and is weakening as the Creative Mind strengthens.

This is shown in the diagram by the placement of the faculties on the line. For reasons that will become clear shortly, the faculty on the bottom end of the line is the one getting stronger. Thus the diagram on the left shows the Will approaching maximum strength and the Creative Mind nearly overwhelmed, while the diagram below on the right shows the Will beginning to weaken while the Creative Mind is resurgent.

This is shown in the diagram by the placement of the faculties on the line. For reasons that will become clear shortly, the faculty on the bottom end of the line is the one getting stronger. Thus the diagram on the left shows the Will approaching maximum strength and the Creative Mind nearly overwhelmed, while the diagram below on the right shows the Will beginning to weaken while the Creative Mind is resurgent.

Now we can draw all these considerations together. Each of the typical positions, with Will, Creative Mind, Mask, and Body of Fate in a specified place, is identified symbolically with one of the 28 phases of the Moon, and represents one human incarnation. Why the Moon? Because in occult philosophy, being incarnate in a material body is the night of the soul, when it sleeps and dreams the dream we call life. That dream is ruled by the Moon, the traditional ruler of dreams, according to its phase. At death we awaken and enter the sunlight—and this, too, will be explored in detail later on in our text.

Now we can draw all these considerations together. Each of the typical positions, with Will, Creative Mind, Mask, and Body of Fate in a specified place, is identified symbolically with one of the 28 phases of the Moon, and represents one human incarnation. Why the Moon? Because in occult philosophy, being incarnate in a material body is the night of the soul, when it sleeps and dreams the dream we call life. That dream is ruled by the Moon, the traditional ruler of dreams, according to its phase. At death we awaken and enter the sunlight—and this, too, will be explored in detail later on in our text.

It’s probably necessary here to insert, for the first but not the last time, an essential warning about these lunar phases: they are not determined by the placement of the Moon in your natal horoscope. Yeats makes this point explicitly in the 1925 version of A Vision, and it follows from the whole structure of the system, yet there’s been a steady stream of authors and astrologers who have ignored this and garbled the system as a result. We’ll discuss this further a little later on. The phase that the Moon was in on the day that you were born does not determine the phase of your present incarnation. Keep this in mind and it will spare you a great deal of confusion.

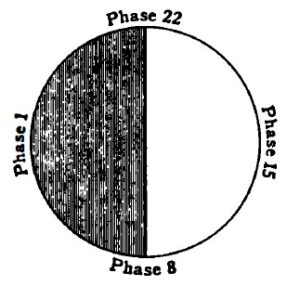

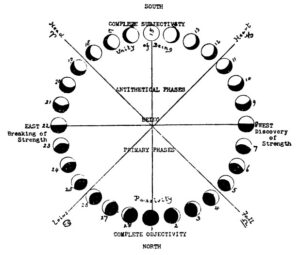

The 28 phases—again, each one labeled according to the placement of the Will—can be mapped out onto the diagram of two cones, as shown on the left. For convenience, though, these phases are more often mapped onto a circle or wheel, as shown on the right.

The result is the fundamental mandala of the system, the Great Wheel. In the 1925 edition of A Vision, this was portrayed as follows:

In the 1937 and later editions, that was reworked by Yeats’s artist friend Edmund Dulac into the diagram below:

(In comparing these, notice that south is straight up in the first diagram, but on the right in the second.)

Once the phases are mapped on the Great Wheel, one of the essential symmetries of the system becomes visible. If the Will is at the point marked 17 on the wheel, the Mask will be at the point marked 3, exactly opposite the placement of Will. The Creative Mind, meanwhile, will be at 13, and the Body of Fate at 27, exactly opposite the placement of Creative Mind. As the phases proceed, Will and Mask move counterclockwise around the Wheel, while Creative Mind and Body of Fate move clockwise. At the 8th and 22nd phases (at the bottom and top of the wheel), Will is in the same place as Body of Fate, and Creative Mind is in the same place as Mask; at the 1st and 15th phases (at the left and right of the wheel), Will and Creative Mind are in the same place, and Mask and Body of Fate are in the same place.

Got all that? Make sure you have at least a general grasp of it before we proceed.

So far, all this has been a matter of abstract geometries, and tolerably dry. It’s at this point that it becomes a bearer of meaning. Each of the 28 points along the wheel has its own distinctive character, and this character can be expressed through Will, Creative Mind, Mask, or Body of Fate, depending on which of these occupies that point. Let’s take the example just given, a person of the 17th phase, and work through it.

The 17th phase has the title of “the Daimonic man”—in other words, the Daimon or higher self of the person is expressed more completely in this phase than in any other. It is nonetheless a difficult phase, because the Will is moving away from its complete fulfillment at the 15th phase, trying to hold onto a vision of beauty that slips through its fingers. Its Mask, the form that it gives to that vision of beauty, derives from the 3rd phase, which (as we’ll see in a later essay) belongs to the first fresh springtime of the soul, as it learns to delight in the body, its senses, and its passions; to a person of the 17th phase, whose Will strives toward this Mask, sexual passion and the beauties of nature are therefore profoundly important, as they give the Will a semblance of the unity and power that is slipping away from it.

That Mask can take one of two forms, for there is a False Mask as well as a True Mask. The False Mask of this phase is titled “Dispersal;” under the sway of the False Mask, or “out of phase” as Yeats terms that condition, the person flails uselessly and throws away his energy in a frenzy of temporary and discordant desires. The True Mask, by contrast, is titled “Simplification through intensity;” guided by the True Mask, the person focuses his or her Will on a handful of images or just one, achieving greatness through sheer intensity of focus.

The Creative Mind of this phase derives from the 13th phase, which is a phase of sensuous delight: the soul in its development has come to a complete mastery of matter and its delights and approaches the vision of beauty through sensual experiences. This strengthens the role of sexual passion in the personality of the 17th phase, but it can do so in two ways: there is a False Creative Mind as well as a true one. The title of the False Creative Mind is “Enforced self-realization”—a person out of phase turns inward where he or she should turn outward, broods and sulks and nourishes wildly disproportionate hatreds and jealousies, all of them engendered by a growing awareness of his or her own increasing incoherence. True to phase, by contrast, the Creative Mind becomes “Creative imagination through antithetical emotion.” The person in phase turns outward and expresses his or her Daimon in a torrent of creative work of some kind.

Then there’s the Body of Fate. This comes from the 27th Phase, a late primary phase. Just as the early primary phases have to do with the discovery of the body and its natural delights, the late primary phases have to do with the renunciation of these things. Reflected in the Body of Fate, the 27th phase expresses itself as “Enforced loss.” This means exactly what it sounds like: whatever the person of this phase most deeply desires will be taken away.

Thus we have a picture of a personality as detailed as you’d get from the simpler forms of astrology, and in some ways more exactly focused. One of the things that makes this picture especially poignant is that it’s a portrait of William Butler Yeats, who identified himself as being of the 17th phase. Look through his biography and you’ll find all the details present and accounted for: the struggle against dispersal and morbid self-absorption, the extraordinary torrent of creative genius when he was in phase, and of course the enforced loss, with his doomed love for Maud Gonne the most significant of these. The phase is also a portrait of certain other great creative minds, including Dante Alighieri and P.B. Shelley, and the same themes can be found in their lives.

There are twenty-five other portraits of equal clarity in A Vision. (The 1st and 15th phases, being pure primary on the one hand and pure antithetical on the other, are never found in incarnate people, who are always a mix of both tinctures.) As we’ll see, these are rooted with equal exactness in biography. All these phases, in turn, reach beyond biography and beyond the human individual, reaching their fulfillment in a vivid and precise theory of historical cycles. This, too, will be discussed in its proper turn.

Assignment: Before next month’s post goes up, read the second section of “The Great Wheel,” titled “Examination of the Wheel.” You’ll probably want to reread the whole text up to that point at least once, too, because much of it will make more sense to you now that you’ve been exposed to the underlying ideas and images.

Playing catch up this morning as I finish up the last reading before plunging on…

This has to do more with the last reading of Anima Mundi, and on the nature of the afterlife, ancestors and metempsychosis/reincarnation. Yeats wrote, quoting Spenser: “Henry More thought that those who, after centuries of life, failed to find the rhythmic body and to pass into the Condition of Fire, were born again. Edmund Spenser, who was among More’s masters, affirmed that nativity without giving it a cause :

‘”After that they againe retourned beene.

They in that garden planted be agayne.

And grow afresh, as they had never scene

Fleshy corruption, nor mortal payne.

Some thousand years so doen they ther remayne,

And then of him are clad with other hew.

Or sent into the chaungeful world agayne.

Till thither they retourn where first they grew:

So like a wheele, around they roam from old to new.’

The dead who speak to us deny metempsychosis, perhaps because they but know a little better what they knew alive; while the dead in Asia, for perhaps no better reason, affirm it, and so we are left amid plausibilities and uncertainties.”

I thought this passage (XIX) was interesting, in that I had been reading part of Benebell Wen’s I Ching book about how in some Asian traditions, there is considered to be two parts of the soul. One is sort of like a recording of the memories of the life that was lived, and this stays active in the afterlife and is what gets communicated with in traditions that incorporate ancestor veneration. The second goes on and reincarnates… I just thought that was a useful way of looking at it, and would make sense from dreams I’ve had of the departed, and also the sense that they have still moved on.

—

In the meantime, thanks for parsing out the images and giving us a life jacket.

This section of Yeats’ book in particular has been instrumental in figuring out what the heck is going on in my life. The addictions, depression, nihilism, loss of purpose, loss of worldview, loss of hope in the external world, lack of self-knowledge, et cetera. Variations of “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” was a frequent refrain for me during that time.

I’m now fairly certain I’ve been in phase 8 in the past seven years with a false mask and a false creative mind.

The vortices diagram makes me think of the french parable “si jeunesse savait, si vieillesse pouvait” (if youth knew, if old age could). As in the vortices work as well for wisdom vs power and not only creativity vs will.

The circle diagram suggests a cycle but the vortices feel like a unidirectional process. Does Yeats suggest can the circle can be traveled more than once?

Thank you for your renaming of Creative Mind as Perception.

I suspected that the phases of the soul did not literally map onto what mansion the Moon was in in one’s natal chart, because if so the position of the Moon relative to the Sun would only be a minor factor in one’s personality, often swamped by one’s other placements.

A month or two ago, I read a book by a neopagan psychological astrologer (Stephen Forrest) who criticized Yeats’ system as inaccurate, and created his own simplified eight-phase system. His system might work for all I know, but I would have to read and analyze a number of celebrity and famous person biographies to find out (and I don’t want to do that).

A quick question: you mention the Mask twice (in position 3rd phase with True/False masks, and also in the 27th phase: “Then there’s the Mask. […]”) – did you mean the Body of Fate in the 27th phase (opposed to Creative Mind in 13th)?

For a bit of humor, does it mean though, if I was born on a full moon, that I might have a latent talent for lycanthropy? Sometimes I feel the need to wolf out, especially when rock ‘n roll is blasting on the radio.

These lunar mansions seem to me to be correlated with age: children enjoy the world-as-is and attempt to change it during late teenage/young adulthood. They peak in the middle years of their life, even if what they achirved in life was not what they originally set out to achieve. In old age, they have to surrender (one way or another) what they have built to the ravages of time or to younger people, before or when they pass away.

Justin, interesting. I tend to take that kind of evidence from spiritualism as a warning that whatever messages come from the Beyond are filtered, sometimes drastically, through the consciousness of the medium, but I suppose there are other options.

Mark, ouch! That’s a very rough road to walk. I hope the knowledge helps.

Rashakor, yes, you can apply the vortices to any binary relationship — and yes, Yeats says explicitly that the wheel is traveled rather more than once.

Patrick, I bet Forrest thought Yeats was giving a system for interpreting moon phase in natal charts. That’s quite common, if silly. The eight-phase system isn’t unique to him — it was invented most of a century ago by Dane Rudhyar, and used (mostly without credit) by various astrologers since his time.

V.O.G., thanks for catching that! I’ve corrected it; yes, it should have been Body of Fate.

Justin, well, do you have hair growing between your eyebrows, and are your index and middle fingers the same length?

Patrick, yes, the wheel also sets out the structure of a single life, and of many other things as well. We’ll get to that!

(Off topic or maybe not so off topic) Hello, JMG and commentariat. Well, there’s been recent personal changes in my life: I’m moving to another house and, though it’s only a change in the same town, it’s always like a little death in our lives. I think every change in life is like a small form of death. I wonder if dying is in a certain mode, like going to live to another home…I hope not to have bored you all with my cheap philosophy about this topic. Thank you for your article about Yeats and the previous comments on that topic.

” I tend to take that kind of evidence from spiritualism as a warning that whatever messages come from the Beyond are filtered, sometimes drastically, through the consciousness of the medium.”

…I can understand that… I’m often of multiple minds about things.

No actual evidence of lycanthropic ability… but the voice of Wolfman Jack has been in the back of my mind this week with regards to an essay I’ve been writing. I’ll leave that to your characters in Carnelian Moon.

On another note, I’m starting to wonder if someone could make a slide rule for these images?

Also, the last bit about Yeats himself, and Shelley and Dante rings very true of other poet biographies as well. A bit of solace there in that… It makes me wonder about the phases young Rimbaud was in, and then where he might have been as the gun runner and explorer of Africa… fascinating.

This model reminded me immediately of the MBST, which is of course based on Jung’s typology, who you said (with good reason) was also an occultist. Primary tincture = extraversion, antithetical tincture = introversion. The people who approach life and the world via their will would be called the Judging types in the MBTI, the people who approach it via the creative mind would be the Perceivers in the MBTI system.

Of course the two systems don’t match exactly; for example, in the MBTI you can be introverted and judging (i.e. trying to impose your will on your surroundings, based on your internal ideas of how things should be, without being overly concerned by external considerations), or you can be extraverted and judging (in which case you become a sort of enforcer of the group consenus). The same goes for the perceiving types. The similarities make it both easier and harder for me to grasp Yeat’s model. Harder, because I need to be careful not to try to ‘fit’ his vision into the MBTI mold.

Wow. I must admit to seeing much of myself in the portrait of the man of the seventeenth phase. It’s taken a lot of work to begin to dig myself out of my scattershot creative efforts and brooding self pity and accept loss. I only hope it’s not too late. Your writings have been a tremendous help to me in this effort and for that I thank you.

Hi that was an enjoyable, knowledge expanding essay on a paradigm of which I knew nothing about. I even read a Keats poem on mask and kind of liked it even though I’m not a big fan of poetry.

Here’s an off topic question: have you read Swedenborg? I hear about him yesterday on a podcast and he has a physical/metaphysical take on things that might align with your philosophical interests. Also, what do you think about “psychic” powers and “remote viewing”? That was part of the podcast as well.

This book is a feast. I sit down to it each time with a large and patient appetite.

I’ve always loved personality typing systems, especially but not only because the incommensurable numbers of types across systems (Big Five, Enneagram 9, Myers-Briggs 16) just go to show that when we talk about human character, we’re talking about something that has more dimensions than can be grasped in a single chart. In honour of certain family members of mine who like to make this point, sometimes while rolling their eyes, I always include in my personal charts an extra category called something like, ‘Type [N]: Someone who doesn’t like to be typed’.

The oppositions between Will and Mask, Creative Mind and Body of Fate, remind me strongly of the dominant and inferior functions in Myers-Briggs. In that system, each personality type has a dominant function, or primary way of interacting with the world, as well as an inferior function, the least developed aspect of the personality, which acts as a lure to the dominant function and unconsciously drives a person’s desires and direction in life. (There are secondary and tertiary functions occupying the ground in between; the overall fourfold symmetry is another striking similarity between MB and Yeats). Dominant and inferior functions are always each other’s exact opposite, and it is quite common to be attracted to someone whose dominant function corresponds to one’s own inferior. The phrases ‘opposites attract’ and ‘she completes me’ are not only relevant here but typologically precise.

Myers and Briggs drew their basic ideas from Jung; I noticed a few chapters ago that the primary tincture corresponds well to Jung’s Sensing function, while the antithetical corresponds to Jung’s Intuition. I think now that I would match Yeats’ Will to Jung’s Judging functions (‘This is how it should be!’) and Yeats’ Creative Mind to Jung’s Perceiving functions (‘But this is how it is.’) Other similarities come to mind, but again, there are incommensurabilities between the systems, and I would have to spend some long, enjoyable hours making charts before I could say more.

Speaking of fourfold symmetries… Yeats, Fortune, Jung, Steiner.

All were contemporaries, all were occultists. Two wrote in English, two wrote in German. Two had respectable public careers and mainstream legacies, two ditched respectability and became all-out alternative.

Yeats died just before the Second World War, Fortune died just after it. Steiner died fourteen years before Yeats, Jung died fifteen years after Fortune.

Steiner wrote extensively about how human souls work in teams, with some members of a team working together on earth simultaneous to other team members working toward the same goals but from the discarnate spiritual world. Of course, those on earth at any given time are working in the ‘dream state’ we call incarnation, while those in the spiritual world are working ‘wide awake’ but with far less capacity to shape events on earth.

Just food for thought- I don’t yet know quite how to piece together the pieces of this puzzle.

While there are certainly a lot of things gyrating in Yeats’ system, it was surprisingly easy to grasp, at least in the basics of the positions and movements. I do have a few questions, which might be answered later in the book.

1. Does one phase correspond to an entire life, or might someone pass through multiple in one life, for example undergoing a significant transformation?

2. What’s the best way of determining which of the phases I’m on? Is there any neat trick other than just mastering the concepts and images in A Vision? Perhaps not so coincidentally, I did a daily one-card tarot reading today in which I ask “What will surprise me most today?” Since that question is usually makes it easier to pair the card with the event in retrospect. I got inverted Strength. Now I notice that phases 22-28 are in the quarter called Breaking of Strength. Maybe that’s a clue telling me to look for myself somewhere in one of those phases. That is, unless something else surprising involving a lack of strength shows up this afternoon!

I’m sure you’ll be publishing a book once this is all said and done. May I suggest a section including something like a “little white book” of the definitions of each of the four terms in each of the 28 phases in your own words? I’ll bet that would more useful for most of us to grasp than Yeats’ version, if he even ends up giving one. It would be a lot of work, I know, but then the book would also appeal to the audience who likes to buy books explaining their personality types, the meanings of their signs, etc. in addition to serious occult philosophers.

Curious how this cycle intersects with masculine & feminine duality.

Upon further reflection on my tarot reading, phases 22-28 don’t seem quite right because I’m strongly antithetical/willing, though working hard to become less lost in my own world and more aware of the objective one, so 16-22 seems like a safer toss of the dart.

Are phases 8 & 22 the ones where the Initiation of the Nadir in Fortune’s system can happen, since they’re points of balance that can take multiple incarnations to definitively cross? Or are they entirely different systems?

“One of the primary differences between occult philosophy and the more respectable branches of philosophy is precisely the distinction between image and abstraction. A quote from Dion Fortune’s The Cosmic Doctrine is apposite: “In these occult teachings you will be given certain images, under which you are instructed to think of certain things. These images are not descriptive but symbolic, and are designed to train the mind, not to inform it.””

I’ve read some philosophy books, but not much books about occultism, and I had suspected there was a subtile difference between “official” philosophy” and the other one, but I hadn´t managed to catch in detail that difference. Now, it’s more clear to me, thanks John.

Chuaquin, every change is a little death, but change is also an inseparable part of life — a reminder that life and death aren’t so different. I hope things work out well for you!

Justin, it would have to be a circular slide rule, but those exist:

Athaia, interesting! Thanks for this.

Tyrell, it’s never too late. Remember that you have an infinite amount of time ahead of you — life after life after life. You might as well get things sorted out now!

Candy, yes, I’ve read a fair amount of Swedenborg, and so did Yeats; Yeats was a big William Blake fan, and Blake was very strongly influenced by Swedenborg. As for psychism — that’s the common occult label for that — it’s real but not always accurate, and yes, that applies very much to remote viewing. Those are useful, and I can recommend a good book for developing your capacities for psychism, but it’s also important not to overstress it or to lose track of the fact that it can be very, very fallible.

Dylan, glad to hear it. By all means spend those enjoyable hours if you feel moved to do so. As for your tetrad, hmm! Interesting.

Kyle, (1) depends on context. Each life embodies one phase, but each life also goes through the entire wheel of phases, and there are also complexities and subdivisions; We’ll get to those. (2) If there’s any such way, Yeats doesn’t give it. (3) We’ll get to that.

Bart, that’s a less important duality in Yeats’s system than it is in modern culture.

Chuaquin, you’re most welcome.

I will need to read all of this again… I felt like I was on a roller coaster trying to envision what Yeats was writing about!

One thing that helped me was a passage from a previous part of the book, imagining the universe as an egg constantly turning itself inside out.

Another thing that jumped right out to me as central to this metaphor was in Yeats’ discussion of the history of this metaphor:

“Alcmaeon, a pupil of Pythagoras, thought that men die because they cannot join their beginning and their end. Their serpent has not its tail in its mouth.”

I’ll need to reread and meditate on it to really process it, but the key to the metaphor I see is this is a complete wavelength. If you’re not seeing the complete wavelength, that only means its being completed out of sight.

One more interesting thing that came to mind was from meditating my way through the sacred geometry oracle. I don’t remember if this came from you or my own meditation, but I had an image of myself as “creator, creation, and canvas” when considering the human canon. I might need to meditate more on this, but at the moment this threefold pattern seems to not mesh well with the dualistic patterns Yeats is explaining.

“When the line slides most of the way over to the antithetical side of the diagram, the Will is strong and the Creative Mind is weak […] When the line slides most of the way back the other direction, the Creative Mind is strong and the Will is weak;”

It is difficult to grasp where this is indicated on the illustration–e.g. the line segment from CM to the shaded triangle is always the same as the segment from Will to the shaded triangle. Does it matter which (CM or Will) is written on top? Or are you perhaps measuring (horizontally) from the whole CM-Will vertical line to the “antithetical” axis, so that when they are close together, “will” is stronger because it identifies with the “antithetical” perspective?

The double triangle has 8 nodes, not 28., so Yeats cannot be mapping the phases of the moon onto these.

Reading your description of the 17th phase, I experienced a shift from “geez, poor shmucks” to “…oh no” as I realized you were talking about me. I feel like you’ve answered a question I didn’t even know how to ask, so thank you.

It’s interesting to me that there are two true/false alternatives — two choice points — with one of them is on the object of the Will while the other is in the Creative Mind itself, not its object. That seems… odd.

I assume there’s no alternative in the Body of Fate because it’s external to your choices; it’s what is regardless of how you feel about it. And I suppose there is no false Will because the Will per se is completely under your control — there is no true Will vs. false Will (but don’t tell Crowley that). Pure objectivity and pure subjectivity have no true/false distinction, only things where are at least a little of both can.

Thank you for the digest. I was wasting time over-thinking material I already grasp. (I didn’t say grip.) Funny that this section makes sense to me while so many find it difficult – including some of my university profs who hated Yeats. My first thought was that I must be doing something wrong, but – no. Seems that Yeats has been so influential and so in step with contemporaries like Jung and Fortune that I’m actually able to read his ideas without throwing the book across the room the way I did with the previous section. (Between the Irish Masterpiece air and me having to scramble to look up formerly common references outside my “modern” education, I didn’t enjoy it.) However, I find it very interesting how influential Yeats has been even on a college success program that I’ve taught.

Hi John Michael,

Dunno about your perspective, but perhaps it’s best if neither the Creative Mind, nor the Will dominate, but rather work in harmony. This of course may be an admittedly unpopular perspective. Presumably Mr Yeats is referring to living consciously, or am I off the mark there?

Ah, the Creative Mind

How the dancers jump and twirl

Energy released

Wanton abandon

Arms held high, then low

Discordant bass notes

Altered states

Smoky dark, abruptly lit

Odd harmonics

Sweet release, the drop

The forgetting

Lost in the moment.

Oh, The Will

Uniform of appearance

Brightly lit

The directing familiar melody

Bodies moving in unison

Heads turned one way

Then the other

All kicking, bowing in time

Observing the form

Becomes the All

Yeah, that’s how I see it: Clubbing versus Line Dancing – and I hate dancing.

Cheers

Chris

Jack, excellent! The wavelength metaphor is particularly good.

Ambrose, I think you might benefit from rereading the essay, because I explained every one of the points that baffle you, in a fair amount of detail. Give it another try.

Slithy, I suspect a lot of people will have that experience as we proceed. As for Will and Body of Fate, exactly. The Will can’t be false, or for that matter true — what’s false or true is what it aims at, which is the Mask, The Body of Fate, similarly, is what it is — but it can be interpreted well or badly.

Rhydlyd, glad to hear it! No question, if you’re attuned to certain currents of early 20th century thought, A Vision makes much more immediate sense.

Chris, maybe so, but that’s not how Yeats saw things!

I stumbled on this last night:

https://yeatsvision.com/Yeats.html

Some great gyre visualizations here:

https://www.yeatsvision.com/Geometry.html

I have yet to look ahead and try to find where my will lands on the Phases of the Moon but I’m getting the sense there is no respite, there is always struggle. This is baked into the dual gyres & restless back and forth movement of the tinctures, always seeking what is not. Good bet there is no respite in the spiritual realm at full Primary in Phase 1 and full Antithetical at Phase 15.

Seems we are in a continuous cycle of churn for many lives with no eventual pay off. Wondering if there is another factor or view from a different (or cleaner or more positive) viewing lens than Yeats was looking through?

If not, then then the Floyd lyrics by the prophet Roger Waters may be pertinent:

“I want to go home, take off this uniform and leave the show……”

Would love for someone to give a more optimistic view concentering A Vision.

Also, I think Yeats’ Vision aligns more with ancient concepts of cycles and I’ll say again, this may have been a big reason that Christianity, Islam, etc., took off. Instead of toiling through long cycles may as well bet it all on one throw of the dice……..

JMG, can the loss – the body of fate’s loss – be productive somehow? By letting go of something you can focus on something else, after all.

And a thought has just come to me in that if our material experience is lunar and the night of the soul then maybe unsaid in Yeats’ system is that we are living a simultaneous existence is solar and in the day of the soul? Not only do we have two opposing gyres on the material but the same on the spiritual and hopefully more positive?

Something that just hit me: astrologers who read Yeats, misunderstood what he was doing, and tried to apply the system in actual astrology all realized it doesn’t work.

Let me say that again: They realized it doesn’t work.

I’m pretty sure that flies in the face of the orthodox picture of astrologers as all frauds (who can make any system seem to work) and gullible morons (who will believe anything regardless of evidence).

JMG @ 21:

“every change is a little death, but change is also an inseparable part of life — a reminder that life and death aren’t so different. I hope things work out well for you!”

Thank you John; me and my family are in the way to the complete change now…Life and death of course aren’t divisible but connected each other. Sometimes is funny, sometimes painful (you know and experience new things, but you need to leave anothers during the changes…).

*********************************************************************************************************

“Tyrell, it’s never too late. Remember that you have an infinite amount of time ahead of you — life after life after life. You might as well get things sorted out now!”

It’s an optimist view, may be true, it can be said we have all the time of the world to be better in our lives…

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Jack # 22:

“One thing that helped me was a passage from a previous part of the book, imagining the universe as an egg constantly turning itself inside out.”

Indeed, an interesting and suggestive metaphor IMHO.

Sigh. I meant to wrote MBTI, and didn’t catch the autocorrect shenanigans…

Hi John Michael,

I have an unfortunate natural tendency towards the mystic, and so please accept my apologies for the difference of opinion. Harmony, dude, is one of my goals, and that plays out here in the land itself which is being shaped. Of course there are always those unfortunate boundary pushers, who take things a step too far, like the now deceased chickens of a fortnight ago. Was Tom Bombadil a mystic or an elemental, or something else altogether?

The mage leans in to other ways and views, and I can respect that. And seriously, dunno about you though, but I’ve always hated dancing. Hope you can avoid that activity on your dating journey. 🙂 There was a rather amusing sub plot in Jack Vance’s book ‘The Face’, with the protagonist Kirth getting roped into a date with a young lady who just wanted to dance… Very funny indeed.

Sorry, but I’m trying to figure out what motivates Mr Yeats, and for once, this is obscure and cloudy. Why ever would he go that path? 😉

Cheers and hope you are doing well.

Chris

In the book, The Solar Way by Nina Roudnikova, part of the Russian circle of occultists around Mebes – in the chapter on number six and the hexagram, she speaks of the figure as a pair of tourbillons or vortexes, one of involution and one of evolution, and talks of the energy interaction between the two. I’ haven’t meditated enough on Yeats’ system here to digest it, but I suspect that Roudnikova’s model is at least parallel to Yeats, and it seems worth mentioning here.

Before we begin, does anyone know what it is with German spammers? Over the past couple of days I’ve gotten well over 300 copies of the same spam message from the same couple of German URLs. Being so mindlessly unimaginative, they’ve all gone straight to my spam folder, where a single click of the delete button sends them to their destiny, but somehow the spammer never seems to notice that all that effort is gurgling down the drain.

This is the second barrage of German spam I’ve gotten, too. This stuff comes in waves; for a while it was escort services in Turkey, and then for a while I got oceans of stuff in Russian and Korean. Now it’s English-language spam from Germany.

Ahem. Anyhow…

Scotty, it’s a useful site; the guy who runs it has also published an equally useful book on A Vision. As for the “churn,” yes, there’s a payoff and a way out, and we’ll get to that. There are also respites from the struggle, at the discarnate phases 1 and 15. More on this as we proceed!

Bruno, it’s a necessary experience, surely. How each person deals with the experience is really up to the individual.

Scotty, in a certain sense, yes.

Slithy, exactly. Astrology is an empirical science. Astrologers — at least those who are any good — adjust their understanding of planetary influences based on experience, and discard things that don’t work.

Chuaquin, well, best wishes on maneuvering through the changes.

Chris, I dislike dancing also, largely because I’m very bad at it — a dancer needs to be able to sense the nonverbal cues that his partner gives and move accordingly, and my nervous system won’t do either of those things. As for Tom Bombadil, he was pretty clearly one of the Maiar, the angelic beings of Tolkien’s theology.

Charlie, an excellent point. Yes, and it’s quite possible that she and Yeats were drawing on common sources.

People as harmonic oscillators cycling between two end states.

The wheel version reminded me of the end view of an electrical generator which produces a sine wave output. Even DC generators want to produce the alternating output but trickery with the commutator gives a pulsing DC output instead.

Add in forcing functions and dampening and you get a very adjustable system. Those mathematically inclined can dig out their physics books or visit the Wikipedia page.. Note that trigonometry and calculus are required.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmonic_oscillator

You never know where this blog is going to wander off to.

@JMG

From what I’ve read, Tolkien’s children had a toy named Tom Bombadil, and he made up stories about Tom Bombadil to entertain them. That is why he doesn’t really fit in Tolkien’s theogony.

Also, yesterday I pulled a tarot card to get a hint about which phase I am in, and pulled the Two of Swords. (Most likely: If my daimon knows, he’s not telling. Alternatively, I’m stuck at one of the two balanced phases.) These phases are hard to determine since I don’t really know what I truly desire yet.

Chris at Fernglade # 35:

You’ve said your tendence to mystic is unfortunate. I guess maybe you’re uncomfortable with our high tech world, it may seem to you flat and dull…Well, I’m not very mystic, but I’m spiritual in my way, and to me this technological world seems apathic and demoralizing. I don’t know if you all share this feeling.

—————————————

Charlie Obert # 36:

I think your brief depiction of those Russian occultists ideas is very interesting, because sometimes I think there are in the Universe involution and evolution forces interconnected. I don’t think every in the world goes fatally towards an evolution, like New Age gurus like to think.

————————————————

JMG # 37:

Thank you! Now I’m between two homes, ha ha…

**********************

Chris and John:

I don’t like to dance indeed, but since I started to date with a woman who now is my actual girlfriend, I’ve started to learn dancing like never before. I dance sometimes with her when we go to music bars, to be honest I do that for his pleasure. Men usually do things like that for reaching women hearts…cough cough. I love her very much, which is always a good subterfuge to do things you don’t like very much…By the way, I’m a mediocre dancer yet, but I’ve bettered since the first dates with her. 🙂

While I am reading re-reading the Yeats chapter along your most-welcome guiding notes I came to ponder if the Heisenberg uncertainty principle doesn’t also apply in this cycle.

As one observes the phenomenon in their own animus/shadow/mind/soul, one creates uncertainty that moves the yardsticks within the twin-vortices.

It feels like the observation only move the yardstick forward though.

Can several cycles be completed in a lifetime? To employ Chuaquin’s metaphor above, can every “little death”(life major changes) be a new starting point at another point in the cycle no matter one’s age?

Last sentence of the paragraph introducing mask and body of fate: “In Yeats’s system, just as the Mask and Creative Mind can be seen as the two ends of a vertical line sliding right and left across the diagram, Mask and Body of Fate are represented by another vertical line that moves together with the first line, but in the other direction.” Probably that first Mask is meant to be Will, as it seems to be in the subsequent illustration.

Hey JMG

Yeat’s system does seem brilliant, but as I contemplate it I do recognise one difficulty.

In astrology, there is no way to be confused about what your horoscope is since there is an irrefutable and objective phenomenon called the celestial objects that unambiguously mark what your horoscope is meant to be. But with the 28 phases of yeats there doesn’t appear to be any equally clear and objective phenomena that marks what phase your life expresses. Instead, it appears that you must have enough self-knowledge and honesty to be able to recognise which phase best describes you, which makes it easy to mistakenly identify with the wrong phase if that is not the case.

Also, completely unrelated, I have finally published my review of that book I talked about a month or so ago, “An Ottoman Traveler”. I tried my best, but it was hard to write a review that did the book justice due to its overwhelming diversity.

https://jlmc12.substack.com/p/an-ottoman-traveler

Siliconguy, one of the things that keeps me blogging is precisely that unpredictability!

Patrick, I don’t find Bombadil a mismatch at all. We know there are Maiar in various corners of Middle-earth, from the Wizards to the balrogs to Melian back in the First Age. They’re idiosyncratic being, but one thing they seem to have in common is that the Ring doesn’t affect them much (consider Gandalf tossing it in the fire without a second thought).

Chuaquin, I admire people who can dance. My nervous system has its problems, and that kind of coordination is one of them.

Rashakor, again, it depends on which cycle is under discussion. In one sense, it’s one phase per life. In another, you go through all the phases in one life. In still others, you might move through a portion of the wheel. We’ll get to that.

Christophe, yes, it was, and I’ve corrected it. Thank you!

J.L.Mc12, I’m pretty sure that’s deliberate. Yeats didn’t intend this for the masses. In its original form, it was available only to subscribers on a private list, so would have gone to people who at least had a good shot at figuring out their own phases.

I feel like I’m following the description of the vortices, except that there’s a twist in the assignment of qualities that I’m not following. The left side is described as maximizing time and subjectivity, the right side space and objectivity. The primary tincture is associated with space and objectivity (outward focused) and the antithetical tincture is associated with time and subjectivity (inwardly focused). Yet, the primary tincture is associated with the left hand side of the diagram – where time and subjectivity are maximum (and space/objectivity is reduced to the tip of the vortex), and and the antithetical tincture is associated with the right side, where space and objectivity are maximized (and time/subjectivity is reduced to the tip of the vortex). I’m catching that there is an orientation aspect, (which way the individual is facing, towards space or time) – so perhaps my error is thinking the length of overlap between the vertical line and vortex is significant?

Hey JMG

If that is the case, I wonder how you would “idiot-proof” Yeat’s system so more people could use it effectively without making mistakes?

Thanks JMG. I am really plodding with this text, and need to read everything again. But your explanation here helps me.

Just mainly wanted to report a synchronicity: I did a reading with the Sacred Geometry Oracle to ask “what do I need to know about living life as an introvert / antithetical tincture kind of person”

So first card, representing myself, is card 8, the hexagram. Now, all the meanings of that might have escaped me, but I had just read Charlie Obert’s comment at #36 which points to some commentary on the hexagram, and its possible connection to Yeats’ system. Thanks, Charlie!

I read the card as saying that I am made up of both the tinctures, and balance can be achieved. (Mmm, in theory at least)

In case you are interested the rest of the reading was equally apropos, and I do thank you so much, JMG, for this Oracle. Always good answers and insights.

[ rest of reading:

2nd card (situation) = card 6 vesica piscis

3rd card (outcome) = card 28 pentagram

Those who have the SGO can look it up in the NSLBB*

* Not So Little Brown Book]

—————————————————————

Thanks to Athaia #11 and Dylan #14 for the correlation with the MBTI. I know enough about that system to be able to see the parallels, and this is helping me in my struggles to understand Yeats’ system.

JlmC 12 #43:

(Well we are a bit off topic now). I’ve seen your link to “A Ottoman traveller”, and I find the comments very interesting. It seems a very bizarre book…I don’t know if there’s a Spanish translation, I’ll seek it but if I don’t find it, I’ll try the English version

——————————————

JMG # 44:

I understand why you can’t dance. One thing is not liking to dance and another one’s when indeed you can’t do it. Yes, I don’t like very much to dance because I’m shy, but I can do it…not very well but I do it.

@JMG

Please feel free to delete this comment if it’s too off-topic. That said, here goes:

Regarding your answer to fellow Ecosophian Slithy Toves, it just reminded me of the shrill meltdowns of mainstream scientists and their fan base in the “science writers” and “my religion is Science” community about astrology. That said, I disagree with your comment about astrology being an empirical science – while I do not think astrology is bogus or quackery (or any of the colourful adjectives thrown at the field by clueless materialists), I do certainly think it’s strictly speaking, not a science; in fact, any attempt to prove that astrology is “scientific” is in itself an example of pseudoscience, IMO.

However, that does not automatically mean that astrology is bogus – that would be basically tantamount to saying that anything that is not strictly scientific is bogus – but then we all know better than to fall for such crap. The funny thing is that we already have another example of a non-scientific field doing one of the main jobs of scientific theories: prediction. To avoid going far too off-topic into Covid territory, I’ll just say that the thousands of mathematical, “scientifically valid” models developed during Covid to predict the spread of the pandemic failed miserably to give predictions of any significant accuracy; interestingly, historians of epidemics and environmental history (one of whom is you) used their knowledge of history and understanding of historical dynamics of epidemics to predict the timeline of Covid spread far more accurately than any of the mathematical modellers by “scientific experts” did. This is instructive in itself: if a non-scientific field like history proved its mettle at prediction by beating science hands down, then what’s to say that astrology can’t, given that it is also non-scientific, and that this example of Covid alone suffices to prove that just because something isn’t scientific, it isn’t necessarily bogus? Something to ponder over and meditate on, I guess…

Hi Chuaquin and greetings!

Respect for your developing prowess on the dance floor, and well, none of us can ever know where this current journey we’re all on will lead. 🙂 As a personal note, as something of a tragic music nerd, you left out the most important of details: Like what kind of movement to which musical form are we talking about here? Wild guess time: Ballroom dancing, but it could be tango? Truly I have no idea, or vibe, so apologies if my guess was wildly off the mark.

In many ways, more formal modes of dancing remind me of the many and varied kata’s drilled and practised in martial arts. There is both grace and fluidity in the learned movements, plus you’re responding to the inputs from the other people. With some complicated kata’s, up to four opponents can advance upon your position, which would be kind of strange if translated to some dance floor burner… 🙂

Far out though! I chose my wife very carefully. Way, way, way, back in the day, and we’re now talking late 1980’s, early 1990’s, my girlfriend of the time used to want to head out clubbing. I tell ya truly, having derived from a mildly economically disadvantaged household, that meant working a full time job, whilst living in share houses, and studying for a degree at University at night. Tired and over worked, I know about such things. Anywhoo, having a girlfriend had many other advantages, and so the compromise was bouncing around in clubs to thumpingly loud music at 1am on a Friday morning. Then being at work at 9am. Truthfully, productivity was not all that great on those days… My dislike for dancing stemmed from that time, and now I’d rather get a proper nights sleep. As you can imagine, eventually club girl had to go. A sad tale of sheer pragmatism, no? 😉

Exactly too! There is a reason I live in a remote spot surrounded by tall forest like a hermit of yore.

Cheers

Chris

Hi John Michael,

Thanks for that. Interesting regarding the Maiar, and if I recall correctly, you also know much upon the subject of moss. 😉 I read your Dreamwidth words of alarm, and agree. Sadly the soft tech folks have not had to incur the very serious capital and recurring costs of their newest creations, and may soon learn a harsh lesson there that a business case must be founded upon realities other than debt. Much wailing and gnashing of teeth will possibly ensue. It is one thing to host a creation on another’s established server, to offering free services whilst also constructing monstrous installations which consume huge ongoing resources. None of that makes any sense to me other than a possible case of over reach.

Of course, it may well be possible that we are forced to subsidise these things. But then! The choice will come down to walking away from all of it, don’t you reckon? It’s such an odd gamble to play, but I don’t know their minds.

And I believe that the principal symbol Mr Yeats is alluding to is the journey itself. A circle which is both a map and a guide where any direction becomes possible if we fail to tread with care.

Cheers

Chris

JMG, about the German spam I don’t know anything; in my own spam folder, there isn’t more spam than usual, and nothing Korean or Russian. Only the usual things. As far as I know, Germany isn’t known as a haven for spammers, in contrast to, for example, Myanmar.

@J.L.Mc12

The occult seems to have a lot of idiot proofing just built into it… I know from plenty of first hand experiences… memory of fingers burned…

@49 Viduraawakened

Astrology is a body of knowledge (hence a “science”) modified or refined by real-world observations (hence it is “empirical”). It even fits the broad definitions of science given in textbooks: good astrologers make and test hypotheses, and eventually* discard what fails to make accurate predictions.

*Despite modern science’s PR, scientists and institutions are generally reluctant to discard cherished theories past their expiration dates, as we’re seeing today with the worsening “Crisis in Cosmology.”

@J.L.Mc12 #46

> I wonder how you would “idiot-proof” Yeat’s system

Two notes from decades of working with computers:

1. An idiot-proofed system is not the same as the original system. Remember when Microsoft tried to idiot-proof Windows and the result was Windows 8?

2. Any time you idiot-proof anything, the universe makes bigger idiots. Smartphones and tablets try to abstract out file management as much as possible because it’s one of the biggest hurdles for non-tech-savvy people in using a computer. The result as been an entire generation who struggle to find a file they just downloaded to their Downloads folder.

Viduraawakened # 49:

” if a non-scientific field like history proved its mettle at prediction by beating science hands down, then what’s to say that astrology can’t, given that it is also non-scientific, and that this example of Covid alone suffices to prove that just because something isn’t scientific, it isn’t necessarily bogus? Something to ponder over and meditate on, I guess…”

I understand you’re upset with the usual scorn against astrology by “Real Believers in Science”, and I see your point of view, but I don’t share it fully. I think History is a real science, because historians use scientific method to validate the better they can their research of past events, including of course the veracity of their sources. OK, is History an exact science? Of course not, but that doesn’t invalidate its researchings. Metheorology isn’t an exact science neither, and is considered a science by majority of pundits. Only a hard-sciences zealot can deny History as science, me think. The case of Sociology is another example of non-exact science, IMHO.

So I think you’re right defending there’s some truth in Astrology, but I think too you’ve chosen the wrong example of non-science.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Chris # 50:

“Respect for your developing prowess on the dance floor, and well, none of us can ever know where this current journey we’re all on will lead. 🙂 As a personal note, as something of a tragic music nerd, you left out the most important of details: Like what kind of movement to which musical form are we talking about here? Wild guess time: Ballroom dancing, but it could be tango? ”

Ballroom dancing of course, I’m too clumsy yet for dancing tango. In addition to this, my girlfriend dances better than I do, but she’ isn’t a real expert in that art…

Thank you for sharing your unfortunate experience clubbing with that girl years ago. Well, I think there are several stages in personal life, and each person life’s different too.

*********************************************************************************************

“And I believe that the principal symbol Mr Yeats is alluding to is the journey itself. A circle which is both a map and a guide where any direction becomes possible if we fail to tread with care.”

Maybe often that what’s really important is the journey, not the arrival…A well known poet from my country said a long time ago somewhat like this (badly makeshift translation): Walker, there’s not a road, it’s made a road when you walk…

Thank you for this summary, it does help make a lot of sense. As someone born and residing outside the Anglophone world, Yeats is remote to me in both time and space. I was deeply confused by many of the expressions he uses. Its clearer to me now.

I am a little curious about the term “Creative Mind”. What is it creating? Is this about how perception of reality is an active process rather than a passive one, as you mentioned in last week’s post? The creation here is the creation of the world based on our senses, is it? Or is it some other reason specific to Yeats, and unrelated to Maya and all that?

Grove, don’t get hung up on left and right. Yeats uses it one way in some diagrams and the other way in others. Primary corresponds to space and objectivity, antithetical to time and subjectivity; in the finished diagram the former is on the left and the latter on the right.

J.L.Mc12, I wouldn’t. I see no point in catering to idiots.

Helen, hmm! Interesting.

Viduraawakened, astrology didn’t come into being because somebody had a theory and set out to make the data conform to it, as many materialists claim. It came into being because astrologer-priests in Mesopotamia spent thousands of years (before 5000 BC-335 BC) tracking the movements of the planets and correlating them to events on earth in a strictly empirical fashion. This isn’t speculation — many of their clay tablet records have been found and translated. Astrology thus emerged as an empirical system of interpretation derived directly from the data; if you don’t want to call that a science, well, what would you call it?

Chris, one of the many interesting things about Yeats’s system is that it can be used to make sense of the business cycle. Yes, we’ll get to that!

Booklover, interesting. Yeah, for some reason I’ve got an insanely persistent but incompetent spammer or two in Germany churning out identical comments that go straight to my spam folder. There were another 40 or so today.

Rajarshi, good! Yeats doesn’t explain, but I read it as a reference to the mind’s active role in creating the universe each of us experiences.

Hey JMG, Slithy Troves, JPM

Ok, maybe “idiot-proofing” was not the right word for what I meant. I was thinking more along the lines of making the determination of you or another person’s phase less ambiguous by correlating it with something relatively objective.

On the top of my head, the best way I could think of to do this would be to figure out if the 28 phases correspond to certain horoscope arrangements, or certain physical characteristics that occult sciences such as palmistry can detect. But that would be a lot of work requiring a lot of research which I doubt would be devoted to something as niche as Yeat’s system.

Hey Chuaquin

As far as I know, there is no Spanish translation. But the book does mention some French, Russian and German translations of Evliya’s book.

Thank you JMG for the “life-jacket” and fellow Ecosophians for your insightful and stimulating comments. I feel like I’ve moved into a new phase of making sense of Yeats’ system. Still slowly re-reading, meditating, laying ground for a better undertanding. Feeling much more attuned and hopeful.

Since the subject of dancing has come up, it’s interesting that dancing is a recurring image in A Vision (the Judwali dancers; the ballet dancer) and in quite a few of Yeats’ poems (“Ah, faeries, dancing under the moon,

A Druid land, a Druid tune!” and “how can we know the dancer from the dance?” are two beautiful examples).

Hi John Michael,

Will reply later this evening, but thought you might be interested in this unrelated item. The story playing out matches what you were saying about heat heading to the poles, except this is the situation in the southern hemisphere: Chaotic weather outlook raises prospects of summer bushfires across eastern states

Cheers

Chris

J.L.Mc12,

I wondered the same. My instinct is that it won’t correspond well to other systems, just as you can’t use Myers-Briggs to figure out your enneagram placement. But it does seem like it should be possible to narrow it down, first by asking myself whether I’m more primary or antithetical (or a mix). In my case, I feel quite antithetical. That eliminates half of the diagram.

The next thing to decide would be whether I’m turning away from the world and inward, or away from my inward self and toward the world. That’s tougher since we go through all or most phases in one life and it could color my judgment. But in my case, it feels like I am turning from a very subjective and dreamy self toward someone who is more aware of the outer world and how it perceives me. So that might allow me to place things between 16-22. As for how to get any closer, I haven’t decided, but I’m reading those types and trying to figure out which one rings true, without falling victim to flattery. It still feels like I need more clarity to accomplish that last step. and I’m sure folks who are 8 or 22 will have an especially hard time narrowing it down, except that those phases probably have very specific characteristics that would help to make them stick out.

Rajarshi # 57:

“As someone born and residing outside the Anglophone world, Yeats is remote to me in both time and space. I was deeply confused by many of the expressions he uses. Its clearer to me now.”

I’m in the same situation of not-Anglophone like you, so I feel exactly the same. Thanks John to be clear explaining Yeats deep thoughts…

———————————————————————————————————————–

JMG # 58:

“Astrology thus emerged as an empirical system of interpretation derived directly from the data; if you don’t want to call that a science, well, what would you call it?”

Indeed, Astrology is the mother of modern Astronomy, and this “dirty” fact is something that some modern astronomers admit reluctanctly, of course grumbling about this uncomfortable origin of their science. However, as you’ve written, there are a lot of records found and translated with lots of hard data made by..astrologers from the past.

————————————————————————————————————————–

JLlmC12 # 60:

OK, thanks for your comment. Of course, with my knowledge I’d read “only” an English or French translation, German and Russian are outside my reading languages…

———————————————————————————————————————–

Goldenhawk # 61:

“how can we know the dancer from the dance?”

A good question for answering, after having meditate it well. I think it hasn’t an easy answer, maybe it’s a paradoxe, because I understand by now the dancer is inside the dance.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Kyle # 63:

“The next thing to decide would be whether I’m turning away from the world and inward, or away from my inward self and toward the world.”

In this aspect I’d like to tell you all I’m clearly more turning away from the world and inward, because I’ve been always trending to introspection…

@ JMG # 58

I am reading the chapter in A Vision, and Yeats uses the analogy of an ex-tempore theater. He says that the Creative Mind is the skill of the actor in blending in with the role he is assigned, while the role itself is his Mask. The actor’s identity and situation constitute the Body of Fate.

Would it be correct to use this analogy here – that the soul is like a traveller who has to make a journey from point A – the B.F. – to point B – the Mask. Their own efforts in the journey constitute the Will. The vehicle they drive with these efforts is the C.M. – is this about right?

@JMG re:German spammers – a friend of mine (an autistic DJ, hello, Erika!) recently told me he has suddenly had an uptick of views on his website….from Germany. So it isn’t just you….

@Siliconguy re: harmonic oscillators. Thank you, thank you, thank you! When I read that phrase, a light went on in my semi-retired engineer brain. I must meditate on this (and probably dust off some old textbooks)

@chris of fernglade re:mystic/dancing. Don’t apologize. Dance is an excellent metaphor. Line dance (all scripted in sync) vs club dance (synchronized chaos) especially

I am a little confused by this part:

> By being is understood that which divides into Four Faculties, by individuality the Will analysed in relation to itself, by personality the Will analysed in relation to the free Mask, and by character Will analysed in relation to the enforced Mask.

This is right after Yeats quotes his instructors mentioning that the soul has at most four circuits around the wheel. I am confused by this paragraph because there are only three here – the Will, the free Mask, and the enforced Mask. What is the fourth element? Is it either the Creative Mind or the Body of Fate?

“Indeed, Astrology is the mother of modern Astronomy, and this “dirty” fact is something that some modern astronomers admit reluctanctly, of course grumbling about this uncomfortable origin of their science.”

I mean, it’s not the only science that had origins in the occult. There’s also the better known example of chemistry originating from alchemy. It’s just that few people practice alchemy these days, while astrology is pervasive in modern pop culture. So chemists feel safe to acknowledge their roots in alchemy because they can paint alchemy as something that superstitious people did in the past and society has progressed from alchemy. On the other hand, astronomers fear that if they acknowledge their roots in astrology it will give credance to the pop culture occult that they are too busy trying to avoid, because too many people still practice astrology.

@ Chuaquin # 64

If I may, which part of the world are you from? I grew up in a relatively privileged family in India, which gave me access to the English language. I wasn’t exactly born with a silver or golden spoon in my mouth, but I had enough opportunities to learn foreign cultures and read loads of books, so I siezed them.

At some point I got on DIscord and engaged with native speakers of English on voice chats. It was hard at first – Discord was wild back in those days and everyone was young, so nobody had any qualms about laughing at my face over my Indian accent. But I adjusted my accent over time, so it is quite passable these days.

Rajarshi # 65:

“Yeats uses the analogy of an ex-tempore theater. He says that the Creative Mind is the skill of the actor in blending in with the role he is assigned, while the role itself is his Mask. The actor’s identity and situation constitute the Body of Fate.”

It’s a good analogy, though I think it isn’t new. If I’m not wrong, I can remember that idea of human life like a theater comes from the European Baroque mindset, at least two centuries before Yeats. However, I admit Yeats analogy use is bright.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

Anonymous # 68: