By the late 1930s William Butler Yeats was an old man. He celebrated his seventieth birthday in 1935; his health, never robust, became increasingly fragile as the 1930s wore on. Gone were the days when he went on lecture tours across the English-speaking world, sleeping on trains to save expenses while giving one lecture or poetry reading after another for weeks on end. The rain and snow that sweep in from the North Atlantic and make Irish winters so bitter were more than his failing health could handle, and since he was no longer a poor man, he had alternatives. That was what brought him to Rapallo.

You can find Rapallo on a map in the northwestern part of Italy, on the shores of the Mediterranean, due north of the island of Corsica. Now as in Yeats’s time, it’s not a big resort town, but attractive scenery, a mellow climate, and modest expenses compared to more popular venues have made it a magnet for intellectuals and creative artists since the 19th century. Among its habitués were composer Jean Sibelius, painter (and occultist) Wassily Kandinsky, and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote his magnum opus Thus Spake Zarathustra while staying there. In the 1930s it was also the home of American poet and general intellectual gadfly Ezra Pound, long one of Yeats’s close friends.

That made it entirely in character for Yeats to begin the second edition of A Vision with an atmospheric introduction about Rapallo, and to go on from there to a summary of the origin story of A Vision and a little letter to Pound. He published it as a short book in 1929, eight years before the new edition saw print. It’s a lovely atmospheric piece—and if you’re left thinking that this is all there is to it, Yeats has suckered you.

Let me pass on one simple trick that old-fashioned occultists know by heart but literary critics have apparently never noticed: it’s important to pay attention to the number of sections, chapters, or volumes in any work written by an occultist from Eliphas Lévi onward. Lévi famously divided each of the two volumes of his pathbreaking occult textbook Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic) into 22 chapters, corresponding to the 22 trump cards of the tarot deck. Lots of people after his time picked up the same habit, and not all of them were explicit about it. Quite the contrary, it became a wink-and-nod by which occult writers clued in those who knew enough to pay attention.

Thus J.-K. Huysmans divided his brilliant novel of fashionable Parisian Satanism, La-Bàs, into 22 chapters. If you know the meanings of the tarot trumps, furthermore, you’ll see the figure on each card appear in the chapter of the same number: a magician in the first chapter, a high priestess in the second, and so on through the sequence. Joséphin Péladan did the same thing, though on a typically more grandiose scale, by writing 22 novels, each of which focuses, you guessed it, on a character who corresponds exactly to the main figure on the corresponding tarot trump. There are other examples, and I’ve yet to see a literary critic mention any of them.

Now take a moment to count the sections of the three parts of “A Packet for Ezra Pound.” I’ll count them with you: five sections in “Rapallo,” fifteen sections in “Introduction to ‘A Vision’,” and two sections in “To Ezra Pound.” Ahem. Yes, Yeats just winked at you.

What makes this even more interesting that it would otherwise be is that there were two different standard orders for the 22 trumps in the occult community of Yeats’s time. There was the order that Lévi used, which began with the Magician and put the Fool between the last two cards, Judgment and the World. Then there was the order used by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and its successor groups, which moved the Fool to the head of the line.

You might expect that Yeats would have used the Golden Dawn sequence in this essay, but he didn’t; the Golden Dawn sequence was still mostly secret in his time, though Aleister Crowley had splashed it around his writings by then, and Yeats would have considered himself bound by his initiatory oaths not to reveal it. The first section of “Rapallo” accordingly begins with a lightly disguised evocation of the four elements, the central theme of Trump I, the Magician, in Lévi’s book and the older occult tarot generally; the second focuses on the duality and complementarity between Yeats and Pound, corresponding to Trump II, the High Priestess; the sequence goes straight on from there, making more or less obvious references to each card in order, until it winds up with the Fool and the World in “To Ezra Pound.”

What makes all this especially charming is that none of it is forced or obtrusive. Here as elsewhere in our text, Yeats is at the peak of his powers as a prose stylist and essayist. Thus it’s entirely possible to read “A Packet for Ezra Pound” as nothing more than a lengthy introduction to A Vision, and enjoy it on those terms. For those who were attentive to occult symbolism, though, it had a twofold message. The first and more obvious part of that message was simply a heads-up to the reader to expect occultism, and plenty of it, in the pages to come. The second and less obvious part was a warning that not all the occult content would be obvious. Keep both these in mind and you’ll get more out of the journey ahead.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at this lengthy introduction with its occult substructure, and see what else we can extract from it. The first thing to look for is the pervasive presence of binary oppositions all through these 22 sections. A Vision, as later posts in this sequence will discuss at length, is structured throughout by the relationship between two pairs of contraries: Will and Mask, Creative Mind and Body of Fate.

The Will is exactly what the word implies, the active, desiring, motivating part of whatever being is under discussion, whether this is an individual, a social or political movement, an age of history, or anything else. What it seeks is the Mask, which is always the opposite of the Will, the sum total of those things absent from the Will that would make the Will complete. The Creative Mind is the perceptive part of the being under discussion, its intellect and understanding; what it perceives is its Body of Fate, the world of circumstances that surround it, and this latter is the opposite and complement of the Creative Mind, the sum total of those things not part of the Creative Mind that the Creative Mind strives to know. The Will seeks to embrace its Mask, the Creative Mind seeks to understand its Body of Fate, and each of these is a quest for its own opposite, the attempt by a light to unite with its own shadow.

Thus it’s not by chance that Yeats starts out the second section of “Rapallo” with the creative opposition between his poetry and criticism and that of his good friend and poetic rival Ezra Pound. Yeats does not exaggerate the difference; it’s hard to think off hand of two early twentieth century poets writing in English whose work is more sharply opposed than Pound and Yeats. The two belonged to different generations—Yeats was born in 1865, Pound in 1885—and their divergent poetic visions are partly a function of their different positions in the slow unraveling of the English-language poetic tradition that reached its nadir with Allen Ginsberg and his ilk.

Yet there’s more to it than that, of course. Yeats was Irish; he was born in a suburb of crowded Dublin but moved to rural Sligo in infancy, and his father was a successful painter who kept in touch with most of the cultural movements of the day. Pound was American; he was born in a tiny settlement in the mountains of Idaho when that was still a territory rather than a state, but moved to New York City in infancy, and his father worked in lumber mills and gold assay offices. Yeats was an occultist, while Pound rolled his eyes at occultism. The fact that the two men occupied opposite ends of the literary spectrum of their day amplified the opposition in their biographies, and their friendship thus made a fine metaphor for the mutual conflict and compensation of Will and Mask, Creative Mind and Body of Fate.

Everything else Yeats mentions in “Rapallo” similarly echoes some aspect of the book to come. The intricate structure of Pound’s Cantos, outlined in section II, hints at the complexities of the 28 phases of the Moon that provide the basic structure of A Vision. So do the quarrelsome and varied cats that Pound feeds in section III, and there’s another contrariety: does Pound like the cats, or not? Notice a second opposition in this same section, between Pound and Yeats’s unnamed friend—this is Lady Augusta Gregory, one of the great pillars of the Irish literary revival and a major influence on Yeats; she was still alive when “A Packet for Ezra Pound” was published in 1929, though she died before the second edition of A Vision saw print.

Note also the wry political satire in section III, which will be repeated in “To Ezra Pound.” By the time Yeats wrote this, his uncritical admiration for the nationalist revolutionaries he knew in his youth had been tempered by decades of bitter experience. He had seen Ireland win its independence in a brutal revolutionary conflict and then plunge straight into civil war. His two terms in the Senate of the Irish Free State doubtless also did much to rid him of any lingering idealism toward the political process, and put an edge on his wry fantasy of organizing the cats in order to exploit them, “and like good politicians sell our charity for power.” His late poetry on the subject is even more harsh. Here’s his “The Great Day” from 1938:

Hurrah for revolution and more cannon-shot!

A beggar upon horseback lashes a beggar on foot.

Hurrah for revolution and cannon come again!

The beggars have changed places, but the lash goes on.

Sections IV and V of “Rapallo” introduces another theme that will be developed at great length in the body of A Vision, the opposition between primary and antithetical approaches to the world. The primary is rooted in the senses, and has to do with the Creative Mind and the Body of Fate, while the antithetical is rooted in the imagination, and has to do with the Will and the Mask. The English tourists whose red-blooded faith comes in for Yeats’s mockery offer a fine first glimpse of what he will call the primary tincture, while Yeats’s own more reflective but more anemic faith is a first sketch of the antithetical tincture. (If you’re not sure how to parse all this, don’t worry about it—we’ll be covering the tinctures in vast detail as the discussion proceeds.)

With the next part of Yeats’s notional packet, “Introduction to ‘A Vision’,” the play of opposites goes on, though here he also provides a tolerably detailed summary of the process by which A Vision came into being. Yeats included among his other occult interests a lifelong fascination with psychic phenomena, which he pursued with characteristic energy as an active member of the Society for Psychical Research. That background shows clearly in these fifteen sections: Yeats is concerned to note down the details of the process and to recount the various odd and eerie events—synchronicities, as his contemporary C.G. Jung called them—that surrounded the communications his wife brought through.

This section also takes pains to present Yeats as a baffled but objective observer who does not take the metaphysical dimensions of the system of A Vision any more seriously than he has to. This is one of the places where it’s most important to keep in mind the importance of masks in Yeats’s thought. I’ll be frank here: when Yeats insists that he thinks of the system purely as an aesthetic structure, a set of “metaphors for poetry” with no objective validity, I don’t believe him.

More precisely, I only half-believe him. It was precisely his point in this book and elsewhere in his work that no point of view is complete, that every belief has to be balanced against its utter opposite if it is to have any chance of embracing truth. Here also, curiously enough, he and C.G. Jung are speaking the same language; Jung’s essay “On Psychic Energy,” first published in 1928, makes the same point, arguing that only an “antinomian postulate” that embraces opposed and mutually irreconcilable visions can express the truth about the psyche.

Here again, though, the mask Yeats dons is another opportunity to prefigure the dance of contraries in A Vision. The point of the system, he claims, is “to hold in a single thought reality and justice”: the first of these two principles belongs to the primary tincture, the second to the antithetical. Yeats and his wife form another pair of contraries, as do the Communicators and the Frustrators, the two swarms of spirits who contended with each other in the process of communication. The records of the communications themselves make it clear that these two classes were by no means the nameless multitudes Yeats suggests here; he and George knew the personal names of members of both categories. That information did not further the image Yeats sought to build in the published version of the system, however, and so it was excluded.

Another important element brought up here is the relation of A Vision to philosophy. Here, for the sake of the mask he had donned, Yeats pretended an ignorance that he did not in fact possess. In his youth he had plunged into William Blake, and absorbed a wealth of philosophic insights from Blake himself and from the writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg, whose work so powerfully influenced Blake. Like every other serious participant in the Golden Dawn, furthermore, Yeats had made a systematic study of the literature of medieval magic and Cabala, with their deep roots in the Platonic and Pythagorean traditions.

Long before the first communications arrived, Yeats had followed up these earlier explorations by reading the works of Thomas Taylor, the Regency-era polymath who translated nearly every surviving word of ancient Greek philosophy into readable English. George, for her part, was even more philosophically literate than her husband; what they might have discussed over the dinner table is another question whose answer never found its way into Yeats’s chronicle. Keep in mind that Yeats is constructing a symbolic narrative out of the raw materials of the experience he and George shared, and you won’t be tempted to take it more literally than it deserves.

The rest of what can be learnt from the fifteen sections of this middle portion of Yeats’s notional packet can be left to interested readers. If they will simply note the figures and contraries in each section and match those up with the corresponding tarot trump, they will have no difficulty reading the message that Yeats has left for them here. Leaving those behind, let’s pass to the last part of the packet, the two sections Yeats titled simply “To Ezra Pound.” These correspond to the last two trumps in the French ordering, the Fool and the World.

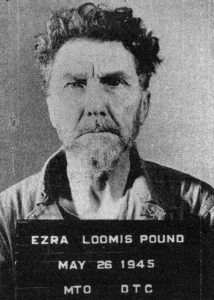

In the first section Yeats passes on a warning that Pound was unwilling to heed. The Fool in the tarot deck is a foolish man in motley about to step over a cliff, toward which he is driven headlong by a barking dog. In Pound’s case, the dog was his own political and economic obsessions and the cliff was his enthusiasm for Italian Fascism, which would have seen him executed for treason after the Second World War if a clique of sympathetic psychologists hadn’t arranged to declare him insane and lock him up in an asylum as an alternative. (To be fair to the psychologists, Pound’s mental state was by no means especially stable by then, though the rigors of the war and its aftermath may have had something to do with that.)

As usual, however, there’s another level to this section. It portrays the world of the primary tincture as experienced by antithetical personalities such as Yeats and Pound: a world of practical politics and business, “all habit and memory,” to which sensitive and high-strung intellectuals such as Yeats and Pound were very poorly suited. Yeats had the good sense to recognize this. Pound did not.

The second section, corresponding to the tarot trump The World, presents the antithetical tincture in contrast to the primary. Here Yeats builds up an opposition of extraordinary intensity. He poses Oedipus, the sacred sacrificial hero of ancient myth, over against Christ, the sacred sacrificial hero of modern myth. He notes that Oedipus, having unknowingly committed the worst sins the ancient Greeks could imagine, lay upon the ground to die, and the redemption he brought to his age was signaled when the earth swallowed him up, while Jesus was traditionally without sin, died in an upright position on the Cross, and the redemption he brought to his age was signaled when he ascended into what Yeats calls the abstract sky.

These again are emblems of the primary and antithetical tinctures respectively, but they also have a relation to historical time. “Every two thousand and odd years”—that is, during each of the twelve zodiacal ages of 2160 years—one of these is sacred and the other secular: one of them the ground of everyday life, the other the contrary toward which an entire age must strive, without ever quite succeeding. The ancient world, in Yeats’s terms, was an antithetical age and therefore sought salvation from a primary redeemer; the modern world was a primary age and therefore sought salvation from an antithetical redeemer—and the age to come, the age Yeats believed was being born around him as he wrote, would be another antithetical age that would seek its salvation from another primary redeemer.

That was the message to which Yeats hoped to awaken Pound, reminding him with one of his own poems that it is these transformations of consciousness, not the squabbling of politicians, that poets are called to proclaim. That message will be central to a very large share of the discussions ahead.

Assignment: Over the next month, if you have the chance, read “Stories of Michael Robartes and His Friends” and the poem that follows it, “The Phases of the Moon.” It’s going to be two months before we return to this, as I’ll be traveling in the first half of June and therefore on hiatus; if you need more reading material, you might make a first pass through Yeats’s essay Per Amica Silentia Lunae, as A Vision is built on the foundation laid in this essay, and so it will be central to a couple of future discussions. You can download an electronic copy free of charge here from Project Gutenberg.

In Desolation Row, Bob Dylan has the line “and Ezra Pound and T.S.Eliot, fighting in the Captain’s tower, while calypso singers laugh at them and fisherman hold flowers”…What do you think was the relationship between Eliot and Pound!?

Pyrrhus, what I think is fortunately irrelevant here, as the details are well documented. Eliot and Pound were close friends — Pound helped Eliot prepare The Waste Land for publication, and Eliot dedicated that poem to Pound. They were both deeply conservative thinkers, though Eliot’s conservatism was a Christian traditionalism and Pound became a fascist. As for why Dylan had them fighting, I have no idea what he was smoking at the time. 😉

It seems that in times like ours, when one age is rising up from the wheel and another is sinking, and the various ways a tincture can pull or repel those currently incarnate, that people are more liable to fall into conflict over the way the collective Creative Mind is being expressed across the Bodies of Fate. Using various Masks to disguise the Will might be apropos in such a situation, so as to avoid knots in the web of fate and pull of destiny…

It seems that what Pound tried to weave really did get entangled on the Loom(is).

“Pound was incarcerated for over 12 years at St. Elizabeths psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C., whose doctors viewed Pound as a narcissist and a psychopath, but otherwise completely sane.”

From the Wikipedia article. It certainly fits the theme of “every belief has to be balanced against its utter opposite if it is to have any chance of embracing truth”.

That “sane except for the insanity” bit takes second place to this case of Russian culture going off on its own;

“Heroic Slavic warriors triumph over evil reptilian invaders to pounding phonk beats. These surreal showdowns have racked up millions of views and spawned a wave of spin-offs, including video games, comic books, and tabletop RPGs. What started as a mock academic lecture quickly turned into a full-blown cultural phenomenon – fueled in part by some deep-rooted medieval nostalgia. One of the most well-known stories in the Ancient Rus vs. Lizards mythos is ‘The tale of how the Russian hero Danila Trumpov drove the accursed Lizards from the Slavic States of America’. In this fictional legend, a Russian version of Donald Trump defeats a shadowy alliance of humanoid lizards, who are supposedly aided by Bill Gates. Trumpov wields imaginative techniques like the “Republican Egg Squeeze” and the “Texas Burger Bomb,” and even manages to sabotage the lizard lobbyists by replacing the dollar with the ruble.”

Someone on this planet still has a sense of humor and there is a poorly documented portion of Rus history that really begs for filling out.

https://swentr.site/pop-culture/617333-ancient-rus-vs-lizards/

Justin, oh, it’s much more tangled than that! Stay tuned.

Siliconguy, ah, so you’ve also encountered the Rus vs. Lizards phenomenon! I’ve been chuckling over that since I first encountered it. I particularly like the story line in which Danila Trumpov drove the lizard people, and their evil ally Bill Gates. out of the ancient Slavic States of America. It really is sane, except for the utter insanity.

JMG,

Thanks for the interesting article!

It’s news to me that Oedipus had a significant cult of worshipers beyond maybe a regional hero practice, and it seems weird to me to compare that to Christ (vs. another saint, like St. George or St. Martha). Was Oedipus more of a universal hero figure than Perseus, Ajax, or Heracles?

Are there other “primary” heroes that would seem more universally admired beyond the Greek diaspora?

Ah-ha! Perfectly sane but for the insanity explains quite a bit in my life. I was just thinking that my education hasn’t been particularly professionally useful and was obtained with doubtful sanity, but I wouldn’t be able to work on The Dolmen Arch or wade into A Vision without it. The non-rationalist, non-materialist aspects of literature were unmentionable by and anathema to my professors – so much so that I gave up on the whole of literature because I mistook “don’t look there” for “nothing there. (Green Wizardry ended up being the key to that gate, btw.) So, I’m looking forward to getting to know Yeats again for the very first time. Many thanks for the introduction.

And thanks to Siliconguy for the Danila Trumpov link. That explains everything.

About 25 years ago I took an adult Ed course on Yeats from a professor who did his PHD on Yeats and had based a lot of his thesis on interviews with Georgie Yeats, with whom he became friends. I don’t remember his dealing much in the course with their esoteric orientation. With his academic position that was perhaps understandable. I wish I had had the background of your essays in taking the course.

I also took a course from him on Pound, which I don’t remember that much of., though I think he focused more on Pound’s literary style than his fascism. I don’t remember how he began his correspondence with Pound, but he was one of few people who was allowed to visit him in prison/mental hospital.

Stephen

Another great read that is fitting of being in a college text book. Lots of threads to investigate. Great job.

Sirustalcelion, Greece didn’t go in for universal saviors in its classical phase; as an antithetical civilization, it had many local saviors rather than one unifying figure. Oedipus happens to be the salvific figure from Greek myth that Yeats (and Lévi, and a great many of their contemporaries) picked up on.

Rhydlyd, I know so many people who’ve been turned off literature by bad professors that I’ve thought more than once that most English professors should be flogged, and then put to work raising piglets, who won’t be harmed by their misbehavior.

Stephen, there’s plenty I don’t know about Yeats, but his occult background and mine have enough overlap that I can point out some things that the literary critics don’t know. I wish I’d met your professor, though! He must have been a fascinating cat.

Peace, thank you! Calling attention to those threads is what I do. 😉

You mention that Pound wasn’t one for occultism, but I think it’s worth noting that his wife and mother in law, Dorothy and Olivia Shakespear, were both Theosophists and members of the Golden Dawn. Dorothy Shakespear was also an ex-lover of Yeats, so, whatever Pound’s personal opinions on occultism were, he would have had a fairly strong second-hand exposure.

Sorry, I meant to say that Olivia Shakespear, Pound’s mother in law, was an ex-lover of Yeats, not Dorothy Shakespear

I have been looking for the contraries in the “Intro to A Vision” section. For section 11, he lists Faculties and Principles, experience and revelation, and understanding and reason. I see experience and understanding as primary and revelation and reason as antithetical, which makes me think that Faculties are primary and Principles are antithetical, except that in section 4 he makes a point of saying there are four Faculties, so are the Faculties just the senses? (And if yes, then why just four?)

Thank you.

JMG:

Regarding Rapallo section 1, I see the invocation of earth, water, and air but I don’t see the fire. Please let me know what I am missing.

Hi John Michael,

Ha! The man doth protest too much! I don’t believe him either.

If someone uses a mask to dissemble an act of will, then that’s an act of will in my books. A tricksy fellow is he.

The distinction between the two points is merely that of a continuum of existence. But either end displays a certain form of striving, to my mind anyway. Dunno.

Curious to see where this journey leads.

Cheers

Chris

That line about politicians jumped out and bit me like a rabid chihuahua.

Also I published the second article today that expanded on the benefits of embracing a more practical version of racism. I wish I had seen this first, as it adds an occult dimension to the idea of how competing cultures can cooperate with each other by pointing out habits and flaws that do not serve the interests of the greater community. On the other hand I’m grateful for the way the events played out, because it was gratifying to develop the concept of opposites as allies on my own and then discover that I might actually be on to something more interesting than just expanding on clickbait titles.

From eighth grade onward I had really great teachers in English lit and language and we went through many great authors, a few of which I detested at the time, but we never touched either Pound or Yeats. Never even heard them mentioned.

Siliconguy and JMG, there’s a lot of things western elites want covered up, about Trump and especially about the Russians, a topic where misinformation rules supreme. Talking about soundtracks, I’ll bet nobody heard of Olga Kassetsky and Eitrack Taeypov and their pioneering role in audio.

Excellent article! There is so little these days that requires serious mental exercise to read–this one does. Perhaps you should have been a professor. I am joking of course–you’d never be hired.

Since 1958, as a freshman, I have watched, and participated in, the steady decline of the college/university system. Oops, wait! Decline from what? It was probably ever thus, there’s just been an increase in noise these days. Your post leads me to think like this.

Thank you very much.

Calliope, true! I don’t claim to know what Pound’s early attitudes might have been like, either — like so many figures of his generation, he may have dabbled in occultism before rejecting it.

Random, no, the Faculties are Will, Mask, Creative Mind, and Body of Fate, and the principles are their equivalents in the higher self, Husk, Passionate Body, Spirit, and Celestial Body. Any of these can be primary or antithetical depending on other factors. We’ll get into all this in due time.

Chris S, the south wind is traditionally associated with fire.

Chris at F, tricksy indeed!

KVD, stay tuned. There’s a lot of material that bears on the theme of opposition as alliance. Have you read Blake, btw?

Smith, who gets deleted from literary history is at least as important as who gets mentioned. Is there a topic where misinformation doesn’t rule supreme?

Tim S, oh, it’s declined. Really bad can always get worse. I considered an academic career twice, but both times had the common sense to back away from it.

JMG@10

Yes my professor friend was a very interesting cat. He served in the 1st Canadian division from just after the Normandy landings until the German defeat, and then got into the English PHD program at University of Michigan with W. D. Auden as his advisor. In those days it was possible to do interesting original work even in the arts, especially, I suppose, if you were a white male. Now someone could probably do a PHD on his PHD and then go on to a career at Starbucks.

Even when I was in college in the 1960s, I considered a career in academia, and with the right choices it could have been an interesting path. Now, not so much. Talking to my daughter’s professors who were retiring in the 2010s., they were all glad that they were getting out of it.

I sense a certain amount of schadenfreude on the blog about the misfortunes of the PMC, as it were, which I feel is not entirely fair. My daughter and most of her friends got degrees because it seemed the way to get a more interesting and better paying job. I can remember a time when she was in college when job applicants without degrees were not considered for even the most menial jobs as a way to avoid looking at half the applications. I don’t think her peers thought they were better than anyone else for their choices. It was just the best way to survive.. If some of these people are now freaking out because of losing their jobs, it is only natural. Carpenters would freak out if there was a ban on building with wood. Yesterday’s best choice is not always today’s. There will be a lot of people who realize they didn’t make the best choice as we proceed on the decline.

Sorry to ramble on. Delete it if you want.

Stephen

Just reaching the end of Per Amica Silentia Lunae and, what do you know, the last part before the Epilogue is numbered XXII. Now I must go back and review it with my Tarot pack!

What Yeats was communicating to Pound seems so timely for today’s world. My problem with a lot of the folks looking at patterns in our contemporary world is they look at patterns from a scientific perspective but leave out history and story. Is it too much of a stretch to say that Yeats was playing Parsifal to Pound’s Fisher King? Thanks for giving us some homework while you are taking some time away. 🙂

Yeats apparently referred to Crowley as ‘that unspeakable mad person’.

Jung’s ‘antinomian postulate’ seems rather similar to the neutral position of the Tibetan Chod tradition. Tibetans shout ‘victory to the gods’ when crossing mountain passes but Chodpa shout ‘victory to the gods and demons’.

Just checking in to say I’m looking forward to this latest book study. I tried and failed with the first two. My grandmother, who came to the U.S. when she was fifteen, was born on a small farm in Sligo. And my good friend in town is married to the great granddaughter of Maud Gonne. And I’ve been dipping into Yeats’ “Autobiographies” over the past year. I’m confident these additional connections will see me through!

I don’t know how this fits into the post. I was reading in the posting about Pound’s insanity in contrast to Yeat’s sanity. At least, that is how I read it.

I have been declared both sane and insane by a judge. When I was young, I ended up in an insane institution for various reasons. Partly because I heard the voices of the Gods. My mother who had worked in them as a student nurse wanted me out. (At the time, it was lobotomy and shock therapy among other treatments.) So she worked hard to get me a certificate of sanity.

What I realized was that sanity and insanity in some ways is a construct depending on how the current society sees it. Now, in the institution, there were truly insane people whose minds simply could not process reality in any form. Then there were the dotty ones who could live in society but on the fringes or with indulgent neighbors. Then there were the rebels who were popped in by their families for simply being different or not following their families’ expectations. I was a cross between dotty and rebel.

I think that Pound’s insanity was a construct as much as Yeat’s sanity. They do balance each other since both in my opinion were dotty. Or they had crystal clear vision that their societies could either accept or not.

Focusing on transformations of consciousness, not the ramblings of shallow politicians.

Timely. Something I need to focus on just now. Politics as derivative of greater changes in the social consciousness.

I will have to re-read that intro now.

Stephen, I can’t speak for everyone here, but I try to reserve my schadenfreude for those members of the managerial caste who, not so long ago, were enthusiastically proclaiming their own self-interested agendas as universal moral truths, and condemning everyone who raised questions about those agendas as evil incarnate. I think a chuckle about them now and again is by no means unearned.

KAN, heh heh heh. Good.

Filho, in a certain sense, yes, that metaphor stands up very well!

Tengu, that doesn’t surprise me at all. Yeats also shoved Crowley down a stair in the “Battle of Blythe Road,” when Crowley tried to seize control of the Golden Dawn’s headquarters on behalf of Mathers, and made a muck of it as usual…

Mrollo, here’s hoping.

Neptunesdolphins, oh, granted, “sane” and “insane” are always value judgments, and always dependent on the values of a given culture. In Pound’s case, there’s good reason to think that the doctors who labeled him insane did it purely as a way to save a great poet from the gallows, so that adds yet another wrinkle to the fabric.

William, excellent! That’s a reaction I hope for.

JMG, you are a cornucopia of scholarly information!…One of my friends was a Harvard English major, and he didn’t know that about Ezra Pound….

Are the 22 trumps from the tarot just a secret handshake or is there more to the story?

Having 22 chapters with corresponding fools and magicians is definitely a wink to the aware, but is it also something else? Does knowing that thr chapters are organized by trump cards unlock anything else in the work?

JMG

Thanks for your reply. I have known, and known of some of the PMC types you are referring to. I guess I have just known a lot more, especially with natural science backgrounds, whose training and interests led them to jobs in academia, NGOs, government, etc. I guess the scythe doesn’t always distinguish the weeds from the flowers.

Stephen

Robert Pirsig: “”Sanity is not truth. Sanity is conformity to what is socially expected.”

Other people have to have some idea of what you are going to do for society to function. Driving is fine example. If your actions are totally unpredictable how far will you get before sheet metal gets bent? Think of two cars going in opposite directions on a two lane road at 70 MPH. The lanes are 10 feet wide, closing speed is 140 mph. The cars will be four feet apart when they pass by. The margin of error is not large, yet accidents are rare because people do what is expected.

You can generalize that concept to the larger society.

As to Stephen Pearson’s comment, as they say hind sight is 20/20. But there is no point of belaboring it. All you can do is make the best decision you can with information you actually have at the time, and remember that indecision is a decision to opt for the status quo. If in 1985 I had known that the American mining industry was going to be selected for destruction in the next decade I would have picked a different major, or at least a different specialization in the field of metallurgical engineering.

What you don’t want to do is ignore information that does not fit your worldview. There is a series on Youtube called The Korean War Week by Week. It is just at the point where MacArthur got fired. The amount information he chose to ignore as the Chinese were setting up their offensive is most impressive. The Chinese are making their own mistakes to the point that the general in charge barged into Mao’s bedroom and screamed at him in frustration because Mao’s orders made no sense given the UN forces had complete air superiority.

Steve Jobs may have had the most effective Reality Distortion Field in modern times, but even so he got fired from Apple, Next was going nowhere, but he won big at Pixar, got back into Apple, made it a success, then died young because he thought a vegan diet would cure his pancreatic cancer. (That particular cancer was the reasonably curable version if you are quick enough.) So won two, lost three?

Parnell came down the road, he said to a cheering man:

‘Ireland shall get her freedom and you still break stone.’

I’ve generally taken this epigram as Yeats’ assessment of Parnell as having an integrity too proud to be an ordinary politician — too proud to pander. But it’s also a comment on revolution as such.

(Yeats, by the way, seems to have pronounced “Parnell” the old, Irish way, with the accent on the first syllable (“Parn’l”). [https://gedmartin.net/martinalia-mainmenu-3/371-pronounce-parnell] It changes the meter of the first line, and thus of the second as well. Yeats’ scansion was always fluid, to the annoyance of his father, but giving parallel scansion to the first clause in each line does make it more interesting.)

Pound’s aversion to occultism is a complex issue, since he was surrounded by it from an early date.

He was tutor, and lover, to the young HD, who followed him to London in about 1911, and HD had quite a connection to esoteric traditions, although it took her a while to begin to sort them all out.. There was an extensive presence of occultism in British literary circles, and even writers who officially disdained occultism were closer to it than might first appear. In addition to the Pound/Years and Pound/Eliot collaborations, for example, there was the link between Eliot and Charles Williams. And so on.

It might be that Pound’s aversion to occultism was primarily rhetorical and poetic, since many occult writers tended to be very “on the nose” about occult ideas and terminology, and use them too directly, rather than putting things, as they say, in their own words. Then again, Pound, like Eliot, may have been in Europe more for the High Culture than for the fertile loam of the back streets and servants’ quarters.

Well, i was having trouble with the idea of how you simultaneously hold an idea and its opposite in your mind.

Then it occurred to me that architecture is a great example.

To make a functional house you need to combine filled space with empty space. You have your solid walls, floors, and ceilings AND you have empty space and pathways that are enclosed. you have solid and static combined with open and flowing. You need both to make a house.

Then it occurred to me that biochemistry does the same thing with water philic and water phobic molecules (and parts of molecules). If you don’t combine both you can’t make an organism.

or chemisty is the combination of heavy, slow, positively charged nuclei and fast, light, negatively charged electrons.

I am willing to bet that if you think about anything that actually functions in the world it combines something and its opposite. (this would come as no surprise to a Daoist )

Pyrrhus, Pound in particular has had his biography, er, “curated” to keep him acceptable as a subject for scholarship. I just happen to read up on things you’re not supposed to read up on. 😉

Team10tim, good! A fine theme for meditation…

Stephen, I envy you their acquaintance! Unfortunately I’ve gotten too meet too many of the other kind. You’re right about the scythe, of course — great social transformations don’t pay a lot of attention to individuals.

Siliconguy, and yet Mao turned out to be right…

LeGrand, another fine example! As for Pound, it’s an interesting question — it may have been that having occultism all around him was part of what made him back away from it.

Dobbs, exactly. It’s not that hard in practice — just remember that each idea implies its contrariety, and make room for both in the world. A match flame is hot compared to your skin, and cold compared to a blowtorch…

JMG

just to add to my last comment, and then I will drop it: I have seen people enforcing their self righteous morality on others all my life in every country I have lived and from all sides of the social and political spectrum. Actually it has been much worse from the right/conservative side than the liberal, and both the moral condemnation and the punishments were far worse. Most of the woke excesses seem just silly. I can remember when it was difficult for women to get a passport or control their own money or their own body. As for non whites it was even worse. Obviously other cultures had their own taboos, though my experience was mostly in the Anglosphere and Europe. The ostracism of an unmarried pregnant woman or the lynching of blacks was was far worse than than being shamed for not calling someone by their chosen pronoun or letting them use the bathroom of their choice.. Sure it went too far, but it was almost farce compared to some of the excesses in my youth in the 1940s,50s, and early 60s.

Stephen

Hrmmm

I would have said a match flame is the combination of the solid wood and gaseous oxygen.

I wonder how many different opposites are combined in a match’s flame?

(is it more or less than the numbers of angels that can dance on the head of a pin?)

JMG:

“Chris S, the south wind is traditionally associated with fire.”

I completely missed that. Thanks, I’ll need to read more closely as we go on.

On the growing rot in US academia:

I’ve been an insider in academia. I quit out of it in 2005 (by early retirement at age 63). That was one of the best decisions I ever made, even though my own university wasn’t yet as far gone into the rot as some others. (I think it was around 1995 that I started to advise undergraduates not to go to graduate school or seek a professional career that required an advanced degree if ever they wanted to have a rewarding life.)

When I went to college myself (1960-1964), all undergraduate students were treated as junior adults, responsible for their actions and choices, and able to learn from their mistakes. One of the turning points for me happened when, sometime in the 1990s in a faculty meeting, our Dean of the College admonished us all never to forget that our students were just young children, who needed always to be protected by us faculty from all adversity. (She included graduate students in her observation, too. ) Ugh! That was one of the big shifts in higher education: the infantilization of the young adult. By now it seems to have reached the point of the infantilization of most adults, young or old, who are not themselves “managers.”

The other was the ever-growing dependence of universities on research grants to fund their growth. (Why grow at all? I asked.) Much of the scientific mendacity and fraud that came to my ears of was meant to keep the grant money flowing, and “justified” to me as such. (And I was in the humanities, so I didn’t get to hear all that much about such things.)

All this, even though my university (Brown) wasn’t as hide-bound as many Ivies back then. It even still had a few professors who studied occult subjects, usually as side-lines: S. Foster Damon, the William Blake specialist, also published on alchemy in The Occult Review and Curt J. Ducasse, in Philosophy, contributed to the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research and The International Journal of Parapsychology. But they were both on the point of retirement when I arrived, and I never had the chance to talk with either of them.

All of which is just to say that our host’s observations on the state of academia seem spot-on to me.

Stephen, it really does depend on who you know, doesn’t it? I personally knew two white working class men who blew their brains out because they couldn’t get work, they couldn’t get public assistance , and the bureaucrats who were supposed to help them told them that their problems were their own fault — all of this because of their race and their gender. They were good men, they wanted nothing more than the chance to contribute to society and support their families, and they were ground down by the hatred and contempt of the managerial class until eating a shotgun shell was the only way out they could find. Their stories were anything but unusual — the people I knew when I lived in Appalachia winced when they heard about the deaths but weren’t surprised — but of course stories like theirs never make the corporate media and never find their way out of flyover country.

Dobbs, yes, you could do it that way too.

Chris, your brain probably isn’t marinated in occult symbolism the way mine is!

Robert, thanks for this.

” the south wind is traditionally associated with fire.”

Does that still apply in the Southern hemisphere?

JMG

It would be fortunate if the pendulum came to rest in the middle, but that would be a lot to hope for.

Stephen

Robert Mathiesen

The rot goes even farther down the line, though in a different form. I worked in the outdoor program at a private middle school in the 90s and early 2000s. Then if a kid fell down or something, you would pick them up, give them a hug and make sure they weren’t hurt. The little ones who were homesick on a trip would sometimes come and sit in your lap around the campfire. Now, unless you are the designated medical person, you can’t touch them. There is such a huge fear of lawsuits and sexual molestation charges that there is a level of fear in the faculty. Two colleagues of mine were barred from the campus over a false sexual misconduct charge that the head of school knew was untrue but enforced because the parents were rich and prone to sue.

Stephen

Siliconguy, occultists in the southern hemisphere squabble about that quite a bit. Never having been there, I have no idea.

Stephen, it may not be entirely out of reach. We’re at peak political divisiveness these days, and when that’s happened before, sooner or later the pressure decreases and the mutual hate dials down a bit.

Hi John Michael,

Just to weigh on the subject of south winds relating to fire, I can appreciate the southern hemisphere perspective of attributing those energies to the north wind, and that makes sense to me. But I’m also not entirely convinced that it matters. The symbolism here is important, but people do also enjoy quibbling. I could just as easily make the technical observation that the westerly winds are equally as troublesome from a fire perspective here, and they’re water (aren’t they?) 🙂 Rain here never arrives from the west, every other direction yes, just not west – that’s geography for you.

Man, it’s unusually dry here at the moment. Not record breaking, but right up there. With this in mind, I’ve been busy attending to the needs of the surrounding forest now while at least it’s cool. Still, the climate here in this particular location is remarkably variable, although the vast majority of the time it’s cool and damp. We’ll see how it goes, but a bit of prudent activity beforehand is probably the path of wisdom.

Cheers

Chris

Le Grand Cinq-Mars–Several years ago, I took a graduate seminar in Modernism is English literature. One of the things I noted was how small the literary and cultural scene was in the London of the early 20th Century. It seemed that everyone was related by blood or marriage or sexual affairs or having attended the same school. People would attend a play by GB Shaw one evening and a metaphysical lecture on Tibetan Buddhism the next and discuss both at tea the following afternoon. I also noted how strenuously academics would avoid the least implication that the occult was important to any respected writer, such as Yeats. This was in the mid 1990s, so discussion of unconventional sexuality was now acceptable. I mean one had had to admit the Oscar Wilde was gay, but for others there had been lengthy and unconvincing explanations that it was not sexual at all to write something like “My dearest Sydney, I long to have you beside me” to one’s secretary. But Yeat’s occult interests were treated as an eccentric hobby rather than as central to his life and art. Very strange.

JMG–The toll on white working-class men in this country has been terrible. Even worse when one considers the slow-motion suicides of drug and alcohol addiction.

RIta

@Stephen Pearson (#43):

Yes, I’ve seen that sort of fear of lawsuits at my old university, too.

And here’s another thign that felt to me like corruption. A daughter of a multi-multi-billionaire family never could get her student act together enough to pass any 32 courses (the number needed to graduate) even in (IIRC) five full-time years on campus. So the administration eventually persuaded some faculty to sign off on her missing course credits, even though she hadn’t taken those courses, by appealing to their compassion — whether compassion for the student or for the university was never made quite clear.

Strictly speaking, all this theater was unnecessary. According to University rules, all course grades are awarded by the University Corporation (the governing body), not by the professors or other teachers. We faculty merely recommend students’ grades to the Corporation. It would not have been much of a reach for the Corporation to have supplied her missing course credits itself.

In all fairness, it’s OK for a university to be extremely risk-adverse these days. One university lawyer of my acquaintance, some thirty years ago, happened to mention that her university had to deal with as many as — IIRC — a dozen or more lawsuits each and every week of the year, most of which were simply predatory or opportunistic. It sounded very much as if there were a whole class of people out there who enrich themselves by filing countless lawsuits against any handy wealthy, but vulnerable, institution. Some of them are even university faculty, who see their own institution’s particular vulnerabilities. [See El Gato Malo’s insightful post on “second world” cultures at boriquagato.substack.com/p/right-on-target]

@Stephen Pearson #36:

The ‘ostracism of an unmarried pregnant woman’ served a function, that of ensuring as few as possible women and children in poverty and dependent on the state. Considering the indebtedness of the modern US and its $1.5 trillion HHS welfare state budget, maybe that wasn’t entirely a bad thing.

Rereading those sections in light of the tarot connection was very interesting, thank you. Though I don’t doubt someone more familiar with the tarot would get much more out of it than I did. Even so, it tickled me that, for example, Yeats’ comment on “what must seem an arbitrary, harsh, difficult symbolism”, the start of a general disclaimer about how he doesn’t really believe in his system, was placed in the section that corresponds to the Moon, which I understand is associated with deception.

On the topic of Pound, it perhaps goes without saying that I had previously and recently encountered allegations that Yeats himself was a fascist sympathiser. Even if he had such tendencies (which is hard for me to establish conclusively), it seems clear that he wasn’t as taken in by it as Pound. His (hard-won?) cynicism had served him in good stead.

The part about oppositions made me think of Charles Fort, who I believe you mentioned before. I’m not sure how seriously you take him as a philosopher (then again, I don’t think he took himself at all seriously, to his credit), but personally I found his musings about how every concept must include its opposite and every thing or notion exists in “the state of the hyphen” between the real and the unreal, distinguished mainly by being comparatively and temporarily more real than each other, to be strangely enlightening. If nothing else, this framework helped me test and tease out the limits of both my convictions and my doubts about the convictions of others. Of course I figured Fort was not the only one to think somewhat along those lines at the time, though I had no idea about Yeats’ philosophy – which, while much more elaborate, seems to have some points in common.

“That was the message to which Yeats hoped to awaken Pound, reminding him with one of his own poems that it is these transformations of consciousness, not the squabbling of politicians, that poets are called to proclaim. That message will be central to a very large share of the discussions ahead.”

Recently, I came across the same way of thinking in Dion Fortune’s writings:

“The initiate works by what he is rather than by what he does…” , also “He works on himself, makes something of himself, and then the forces that radiate from him without effort on his part bless and illuminate” (Ref: The Magical Battle of Britain – Letter 51).

This philosophy must have come from Golden Dawn teachings but I wonder where the original school of this thought came from?

For anyone looking for second hand copies of the 1937 A Vision, this might be useful:

My experience of Amazon Marketplace, abebooks etc. is that almost all copies of A Vision are described as the 1925 version, or shown with a stock photo of the same.

I got the A Norman Jeffares version published by Athena (thinking I would need the 1925 anyway, so what the heck) to be pleasantly surprised that it was, in fact, mainly the 1937 material.

https://www.biblio.com/book/vision-related-writings-yeats-wb/d/1550065383

William Hunter Duncan wrote:

Focusing on transformations of consciousness, not the ramblings of shallow politicians.

Timely. Something I need to focus on just now. Politics as derivative of greater changes in the social consciousness.

—-

To JMG: I am sorry I missed that in the post. Where is it about? And what does it mean? Are we seeing signs of greater changes in social consciousness. I keep missing that. What I see is mostly the anti-Trump screaming. Or is that a change since the screamers can’t seem to gain traction with the great population, and scream louder.

>Why grow at all? I asked.

Because the debt ponzi demands it. Baked into the rules we all play by. Sad thing is they don’t know why they’re doing what they’re doing.

Very busy this week (having a wedding) but just wanted to drop in to say that I read the chapter and loved it, and definitely didn’t catch the secret 22 handshake and a lot more!

Chris, I know people who use the standard northern hemisphere symbolism in your country and get good results from it. For that matter, here in Rhode Island the ocean is to the south, but I still invoke water in the west and get an answer.

Rita, thank you. It appalls me how few people are even willing to admit that such things have happened, and are happening.

Daniil, excellent! Yes, the Moon is a useful flag for misdirection. Yeats was affiliated for a while with the Irish Blueshirts, as close to a fascist movement as the Irish Free State ever got. There’s a tolerably good summary here. As for Charles Fort, he’s long been a major influence on my thinking; I see him as one of the great intellectual heretics of his age, and his mocking antiphilosophy is far more profound than that of the allegedly serious thinkers who sneer at him.

Scotty, that’s a fascinating question to which I don’t happen to know the answer. It pervades Taoist thought — Lao Tsu’s whole system presupposes that an individual who wants to bring about constructive change ought to focus on getting right with the Tao, and then the relevant changes will happen by themselves — but I don’t think Taoism was well enough known or understood at the time to be a likely source.

Matt, the Norman Jeffares edition, which includes several additional works, is very good — it includes Per Amica Silentia Lunae, for example. Glad you found a copy.

Neptunesdolphins, I commented as follows in the last but one paragraph of the post: “That was the message to which Yeats hoped to awaken Pound, reminding him with one of his own poems that it is these transformations of consciousness, not the squabbling of politicians, that poets are called to proclaim.” My commentariat, in their usual ebullient way, took that and ran with it. I suspect that being inside the DC beltway makes it hard for you to hear anything but the shrieking, since it’s the bureaucratic elite that’s getting worked over with a pruning hook just now. The only changes in social consciousness I’m seeing in general is that Trump’s approval ratings are rising again while the Democrats’ are still deep in the toilet; what I’ve noticed, rather, is that people here and there seem to be noticing that changing themselves is more useful than trying to get the rest of the world to change so that they don’t have to.

Isaac, congrats to all involved in the wedding!

@Daniil Adamov (#49), on fascism in the West, and particularly in the USA:

My father was a mechanical engineer working on military weapons systems (the Norden Bombsight) in the years before the USA entered World War 2. He made a point of telling me as a matter of history, before I went off to college, that of all the people he knew from work–engineers and military officers–only about one-third wanted to enter the war on the side of the Allies, and another third wanted the US to stay out of the war altogether. The final third greatly admired Germany for its science and its eugenic policies, and very much wanted the USA to enter the war on the side of the Nazis. After Pearl Harbor, once the USA entered the war, that final third didn’t change its views, but simply went underground until the time would once again be right for them to come out of hiding. That’s what’s happening now.

So Nazi-ism isn’t anything new in the USA, and probably not in the UK, either. It’s just come out of hiding once again.

(I haven’t seen many Europeans (including Russians) who are aware of how close the USA came to entering World War 2 on the side of the Nazis. This forgotten fact explains a fair amount of what is now going on in Ukraine.)

(Just to clarify, my father was a Danish-American. All four of his grandparents born in Denmark, and three of them had fled Denmark for the USA in the wake of Prussia’s invasion of their homeland in 1863-1864. He had no love for Germany, and very much admired what Denmark was doing to oppose its German and Nazi military overlords during World War 2.)

@JMG (#55):

As it happened, Taoism was fairly well known in Theosophical circles,. thanks to Isabella Mears’s translation of Lao Tze. It was originally published in 1916 in Glasgow, but in 1922 it was reissued with revisions by the Theosophical Publishing House in London (downloadable from google books and elsewhere).

It seems to me that Yeats picked the most beautiful, erudite, elegant, and thoughtful way possible of calling his friend an ass. Looking forward to the deep dive on this book and your new edition from Aeon.

I see in the comments some talk of the toxic polarization afflicting the USA. In one respect it can be thought of as magical combat. The two sides become totally enmeshed in each other. A curse flung at another links you to the person you cursed via raspberry jam. Retaliating only furthers the cycle.

These two images rather explain the cycle:

Polarization Trap:

https://static.wixstatic.com/media/a5ee20_954c0fe0a51a48b0b141177de21b2919~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_1143,h_1075,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/a5ee20_954c0fe0a51a48b0b141177de21b2919~mv2.png

Magical Attack:

https://www.redbubble.com/i/sticker/Magical-Attack-by-CassBeanland/80515986.EJUG5

Opting out, and talking in ways less likely to just push each others buttons, is one way to end the cycle. The author Zachary Ellwood has also written essentially two versions of a book that might be useful. “Defusing American Anger” for a general audience and “How Contempt Destroys Democracy” aimed at liberals.

Off topic, but has anyone drawn your attention to the USDA report on Fireless Cookers yet? It’s good, has a lot of resources, but the main reason I think you’ll be interested in seeing it is that it directly quotes and cites Green Wizardry.

https://www.nal.usda.gov/collections/stories/fireless-cooker

WHD #26 said – “Timely. Something I need to focus on just now. Politics as derivative of greater changes in the social consciousness.”

I so appreciate your comment. This is exactly where I am at is really learning to see the forest while still being aware of the trees.

JMG, thank you for this book club. My being has been hungry for something this meaty to chomp on. I relish the challenge as I shift out of the US educational mindset of getting the “right answer.” This may also finally help me get consistent about discursive meditation. 😄

“William Blake. Like Yeats, he was up to his eyeballs in esoteric traditions — a detail many of both men’s more recent interpreters have tried their best to ignore.”

Last year I read William Blake vs. The World, by John Higgs. He alternates between biographical sections about Blake, which I enjoyed, and sections about how Blake’s thought actually agrees with all the latest neuroscience and physics and so on. Who knew that Blake was secretly in cahoots with Daniel Dennett? It’s an immensely frustrating read.

Anyway, so far I’ve found “A Vision” to be engaging but immensely obscure. Your commentary is going to be invaluable, I think.

I confess some difficulty in getting the tarot references. Aside from the fool (which correspondence seems obvious one pointed out – probably an in-joke of Yeats’ I guess), these largely seem opaque to me.

So I went back and reread Dogma chapter One to try and get some traction. The best I could come up with was that the Bataleur / Mage needs to be King and Priest – which would seem to correspond to the Primary and Antithetical you discuss. However in the first section of Vision, the main binary seems to be between the common people in town and the far off rich people. Both of these groups seem to be worldly, so I’m not seeing an Antithetical element that might correspond to the priestly function. Am I entirely off in these speculations?

I will mention that re-reading Dogma chapter one, I understood and noticed a lot more than two years or so ago. That did make me feel like even if I’m a dunce about this stuff, even dunces can improve in their own mediocratic way 🙂 I do attribute this to studying with you, so many thanks.

>Partly because I heard the voices of the Gods

I have to ask how did you know they were Gods and not the equivalent of some nonphysical stoner dude? Did you just believe them when they told you? And while I’m asking odd questions – what did they say?

JMG, Robert Mathiesen,

I think we had this discussion years ago about the prevalence of fascist sympathy and more in the western world in general. It was certainly wide spread in the UK and US. Many middle and upper class people viewed it as much lesser evil than Bolshevism (communism) and even as a defense of European culture against it. My father, who was a British WWI veteran working for a British firm in NY would certainly have leaned that way until WWII started. it would have been one of the reasons for the early collapse of the French army in WWII, in that many of the officers were pro fascist, while many of the men were communist, and didn’t want to fight Germany while the Molotov Ribbentrop non aggression pact with the USSR was active.

The 1930s were a time of huge turmoil in Europe, and Yeats would certainly have supported whatever he felt defended European culture.

Ireland was one country, like Italy and Germany that had troops on both sides in the Spanish civil war, although not serving members of the armed forces like the latter two. The Blue Shirts did have the blessing of the church and much of the government though, unlike Frank Ryan’s men in the International Brigades. Yeats actually refers to Owen O’ Duffey in one of his earlier poems, though not by name, as the brown lieutenant.

One of D. H Lawrence’s novels, Kangaroo, was about fascism in Australia at that time.

Stephen

JMG

Upon reflection, many of the examples of conservative repression of women, minorities, etc that I referred to in our earlier exchange were from 1940s,50s and early 60s.. They seem quite recent to me, but probably feel like ancient history to most readers. That is what being 85 will do to you. When my daughter was growing up, as a mixed race girl, in the 80s, 90s and early 00s, there didn’t’ seem to be much prejudice or favoritism towards her in US, Australia or Europe.

Stephen

Robert, thanks for this. I wasn’t aware of that!

Kimberly, doubtless that was part of it!

Eagle Fang, excellent. Yes, exactly.

Moose, no, I hadn’t! Good heavens. I’m gobsmacked.

Angelica, if it does that, I’ll be delighted.

Cliff, oog. That kind of thing annoys the bejesus out of me.

Paul, you need to start with a good solid knowledge of French tarot symbolism and then apply the symbols of each card to the symbols in each section. You need to focus much more finely.

Stephen, exactly. It was much more nuanced than it’s been made out by later propagandists.

“It’s complicated.”

Michael Tratner’s “Modernism and mass politics : Joyce, Woolf, Eliot, Yeats” Is an interesting treatment of two people on the Naughty side (Eliot and Yeats) and two people on the Nice side (Joyce and Woolf), both sets, in the author’s account, united by a turn away from “bourgeois individualism” in literature and toward “literature from a mass point of view.” He takes as a starting point the widely read book by Gustave Le Bon, “The Crowd”, which he treats as a kind of prodromal manifesto of Modernist esthetics.

Basically, he treats “fascism” and “socialism” as both forms of orientation toward the masses, and Modernism as a turn from the bourgeois individualism of Victorian literature toward a deeper engagement with the collective life. It was published in 1995, and, as with all such books, one of its points of interest is seeing how it stacks up now.

One of Tratner’s big problems is that he doesn’t know what to do with Yeats’ occultism. Not only does he dismiss it as a sort of irrelevant or eccentric ornament, but he’s actually unable to read many of the poems that deal with politics simply because he can’t make the kind of sense of them that Yeats intended. (See the verses from “Under Ben Bulben” that I excerpt below — deeply enmeshed in Yeats’ system, but Tratner treats part III as an indulgence in bad temper.)

His section on Eliot, however, is very interesting (though he doesn’t seem to know the difference between Catholic and Anglo-Catholic). Anyone interested in understanding Lovecraft could profit from reading the chapter on Eliot. Unfortunately, he doesn’t do much with Pound’s work as tutor in poetics to both Eliot and Yeats.

Finally, it’s important to remember that Fascism (especially as exemplified by Mussolini) was widely admired not only by the many, but also by officials in the Roosevelt administration, including FDR. Remember that we’re dealing here with people for whom technical. managerial, “scientific”, procedures were central. (One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”)

(He writes rather admiringly, in connection with Woolf, about Harold Laski’s idea of representative government representing not unitary individuals (bourgeois!), but, constituencies, and thus each individual’s multiple (intersectional!) identities. So that a woman dentist Olympic athlete would vote for a representative of women, a representative of dentistry, a representative of athletes, etc. He does not mention whether this would involve attending political meetings for each of one’s intersecting identities. L’enfer, c’est les autres.)

***

Many times man lives and dies

Between his two eternities,

That of race and that of soul,

And ancient Ireland knew it all.

Whether man die in his bed

Or the rifle knocks him dead,

A brief parting from those dear

Is the worst man has to fear.

Though grave-diggers’ toil is long,

Sharp their spades, their muscles strong.

They but thrust their buried men

Back in the human mind again.

III

You that Mitchel’s prayer have heard,

‘Send war in our time, O Lord!’

Know that when all words are said

And a man is fighting mad,

Something drops from eyes long blind,

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace.

Even the wisest man grows tense

With some sort of violence

Before he can accomplish fate,

Know his work or choose his mate.

As for Blake and neuroscience, David Worrall’s “William Blake’s Visions: Art, Hallucinations, Synaesthesia” is actually worth reading (if you can find a copy in a library: generally it’s an arm and a leg, and then some). I’ll say more about it on some other place, but since Blake and neuroscience came up, I thought I’d mention it.

It’s a pretty sensitive treatment of Blake’s art and his visions, from the point of view of the neurology of visual hallucinations — despite the fact that, again, Worrall doesn’t really know what to do with the “metaphysical” or spiritual content of Blake’s work, or experiences. He treats the visionary experiences fairly and sensitively, right up to the point where he might have to deal with what they mean, or how they might mean. At that point, a discreet curtain falls on the discussion. But it does provide a very useful review of the neuroscience.

One of the author’s quirks is that he wants to defend Blake’s visions from being treated on “psychological” terms, which for him would mean pathological. If they are neuroligocal events, no blame!

As for the French surrender in WWII, Ernst Juenger (in “the Peace”) makes the plausible point that part of the motive at least was to “collapse now and avoid total destruction”. People at the time could not quite imagine what surrender and occupation would actually be like. And, to be fair, they were not utterly wrong. Unlike many countries on the eastern front, for whom no plausible version of that choice existed, though some tried.

About the change in consciousness:

JMG:

These again are emblems of the primary and antithetical tinctures respectively, but they also have a relation to historical time. “Every two thousand and odd years”—that is, during each of the twelve zodiacal ages of 2160 years—one of these is sacred and the other secular: one of them the ground of everyday life, the other the contrary toward which an entire age must strive, without ever quite succeeding. The ancient world, in Yeats’s terms, was an antithetical age and therefore sought salvation from a primary redeemer; the modern world was a primary age and therefore sought salvation from an antithetical redeemer—and the age to come, the age Yeats believed was being born around him as he wrote, would be another antithetical age that would seek its salvation from another primary redeemer.

That was the message to which Yeats hoped to awaken Pound, reminding him with one of his own poems that it is these transformations of consciousness, not the squabbling of politicians, that poets are called to proclaim. That message will be central to a very large share of the discussions ahead.

—–

Me: I think I understand this to be Yeats thought that the modern age that came after him needed a primary redeemer.

What is a primary redeemer? I keep harking back to Christ, but I am not sure if that is what Yeats meant.

About change of consciousness, I was reading about the history of measurements. Going from feet to meters. As long as people measured in feet and yards, they were tied to the human body since that is how feet were first measured. When switching to the metric system of base 10, it changed how people related to measurement. Since the body does not measure in base 10, people became machines tooled for efficiency. I would that say that is a subtle change – from living in the physical world of the body to becoming a 24/7 machine.

About poets and change of consciousness,

I remember reading a review of Amanda Gorman’s poem at Biden’s inauguration. She was hailed as the poet of the hour and her poetry was profound. What the poetry review said was that she just simply jotted down memes off of social media and strung them together. It was not poetry but simply memes that people found profound – the people who supported Biden.

Here is the poem she wrote:

“Here’s to the women who have climbed my hills before,” Gorman tweeted.

Here is the text of Gorman’s poem, “The Hill We Climb,” in full.

When day comes, we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

The loss we carry. A sea we must wade.

We braved the belly of the beast.

We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace, and the norms and notions of what “just” is isn’t always justice.

And yet the dawn is ours before we knew it.

Somehow we do it.

Somehow we weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.

We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president, only to find herself reciting for one.

And, yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine, but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

To compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters and conditions of man.

And so we lift our gaze, not to what stands between us, but what stands before us.

We close the divide because we know to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside.

We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another.

We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true.

That even as we grieved, we grew.

That even as we hurt, we hoped.

That even as we tired, we tried.

That we’ll forever be tied together, victorious.

Not because we will never again know defeat, but because we will never again sow division.

Scripture tells us to envision that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree, and no one shall make them afraid.

If we’re to live up to our own time, then victory won’t lie in the blade, but in all the bridges we’ve made.

That is the promise to glade, the hill we climb, if only we dare.

It’s because being American is more than a pride we inherit.

It’s the past we step into and how we repair it.

We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation, rather than share it.

Would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy.

And this effort very nearly succeeded.

But while democracy can be periodically delayed, it can never be permanently defeated.

In this truth, in this faith we trust, for while we have our eyes on the future, history has its eyes on us.

This is the era of just redemption.

We feared at its inception.

We did not feel prepared to be the heirs of such a terrifying hour.

But within it we found the power to author a new chapter, to offer hope and laughter to ourselves.

So, while once we asked, how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe, now we assert, how could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

We will not march back to what was, but move to what shall be: a country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free.

We will not be turned around or interrupted by intimidation because we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation, become the future.

Our blunders become their burdens.

But one thing is certain.

If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright.

So let us leave behind a country better than the one we were left.

Every breath from my bronze-pounded chest, we will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

We will rise from the golden hills of the West.

We will rise from the windswept Northeast where our forefathers first realized revolution.

We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states.

We will rise from the sun-baked South.

We will rebuild, reconcile, and recover.

And every known nook of our nation and every corner called our country, our people diverse and beautiful, will emerge battered and beautiful.

When day comes, we step out of the shade aflame and unafraid.

The new dawn blooms as we free it.

For there is always light, if only we’re brave enough to see it.

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

—

I think the reviewer is right. Gorman is also an activist and a darling of the Democrats. I wonder if anyone’s consciousness was nudged in anyway. It does seem to be a lot of platitudes strung together. I personally was left cold by it. Yeats on the other hand (and even Pound) seem to work hard at crafting their work. Although Yeats was more profound in his.

The Other Owen.

>Partly because I heard the voices of the Gods

I have to ask how did you know they were Gods and not the equivalent of some nonphysical stoner dude? Did you just believe them when they told you? And while I’m asking odd questions – what did they say?

——-